Signor Marconi's Magic Box (31 page)

Read Signor Marconi's Magic Box Online

Authors: Gavin Weightman

Jack Binns was the archetypal Marconi operator. Born in Lincolnshire in 1884, he had shown an interest in electrical science and had got a place at a technical school run by the Great Eastern Railway. He learned Morse code and the job of the telegraph operator, and was an ideal candidate for the new world of wireless telegraphy. After he joined the Marconi Company he was sent to Belgium, and became an operator on a German ship fitted with Marconi wireless. He might have stayed there had Germany, which was still campaigning to bring the Marconi Company into line, not made the decision to dismiss all foreign operators from its ships. Germany had established at the Berlin Radiotelegraphic Conference of 1906 that the international distress signal should be its own: the letters ‘SOS’, which in Morse is three dots, three dashes, and three dots. Marconi operators chose to ignore this ruling, and continued to use their own distress call, ‘CQD’. Out on the Atlantic the chances were that wireless operators would know each other personally, and Marconi men could behave as if there were no international rules or laws governing their behaviour.

The first news-sheet ever produced on an ocean liner with reports transmitted from the shore by wireless. Returning from New York in 1899 on the SS

St Paul

, Marconi persuaded the captain to allow him to use the print room to produce the

Transatlantic Times

, with news sent from the Royal Needles Hotel. Passengers paid $1 a copy, which was donated to a fund for seamen.

St Paul

, Marconi persuaded the captain to allow him to use the print room to produce the

Transatlantic Times

, with news sent from the Royal Needles Hotel. Passengers paid $1 a copy, which was donated to a fund for seamen.

A love letter from the American heiress Josephine Holman, who Marconi met on the liner

St Paul

in 1899. The shipboard romance had led to a secret engagement. Back home in America, Josephine wrote some of her letters to Marconi in Morse code in case her mother, who did not know of her engagement, found them.

St Paul

in 1899. The shipboard romance had led to a secret engagement. Back home in America, Josephine wrote some of her letters to Marconi in Morse code in case her mother, who did not know of her engagement, found them.

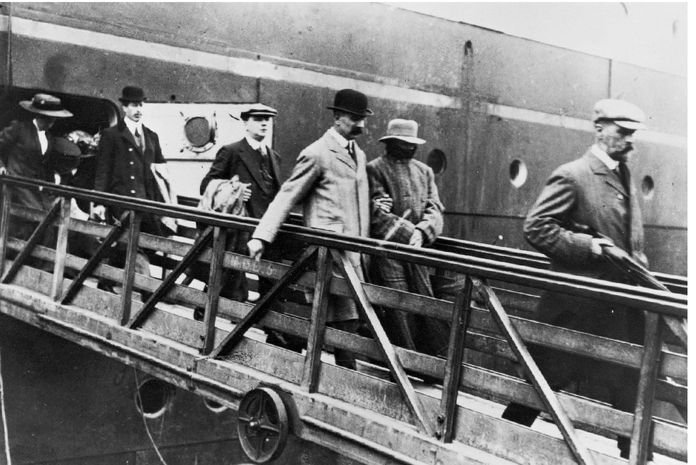

The wild and desperate scene of Marconi’s greatest achievement, which astonished the world and was greeted with scepticism by many scientists. Here he watches as helpers attempt to get a huge kite airborne at St John’s, Newfoundland, in December 1901, to carry an aerial with which he hoped to pick up a signal from Cornwall on the other side of the Atlantic.

The proof Marconi needed to dispel doubts that he could send wireless signals more than two thousand miles: a chart, signed by the captain and first mate of the SS

Philadelphia

, confirming the distances Morse messages were received as the liner sailed from Southampton to New York in February 1902.

Philadelphia

, confirming the distances Morse messages were received as the liner sailed from Southampton to New York in February 1902.

A ‘magnetic detector’ devised by Marconi in 1902 to replace his earlier receiver, the coherer. Though it looks makeshift in its cigar-box housing, and included a motor cannibalised from an Edison phonograph and coils made of florists’ wire, the ‘maggie’, as wireless operators called it with affection, served Marconi well for many years, and was the prototype of the receiver used on the

Titanic

.

Titanic

.

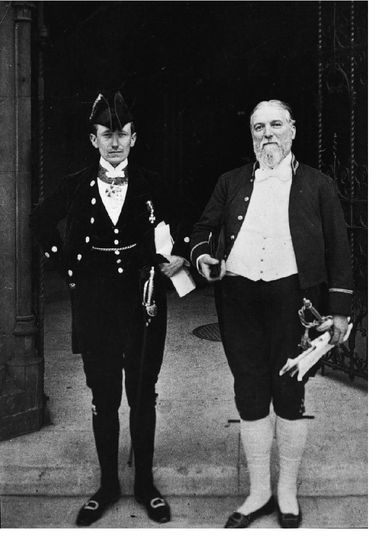

A favoured, adopted son of the British upper crust, Marconi is here decked out in some kind of ceremonial regalia as he accompanies his friend Sir Henneker Heaton MP to a bash at Westminster to celebrate Edward VII’s coronation in 1902.

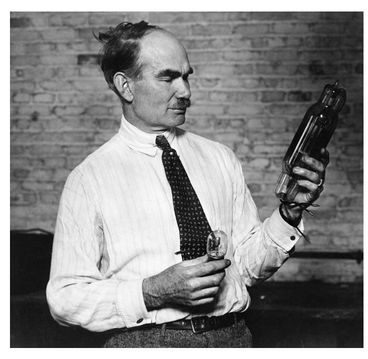

A thorn in Marconi’s flesh for many years, the boastful and eccentric American Lee de Forest, posing with his claim to fame, the ‘audion’, an early wireless valve, and a later, miniaturised model. De Forest styled himself ‘the Father of Radio’, but all his claims to inventive originality were hotly disputed.

American wireless pioneers and their unscrupulous backers were keen to convince a gullible public that they had beaten Marconi at his own game. This exhibit, put on at the St Louis World’s Fair in 1904 by Abraham White, the fraudster who funded Lee de Forest, claims, with some justification, two ‘firsts’: the Morse-code car-phone, and the use of wireless in war, to report on naval battles between Russia and Japan.

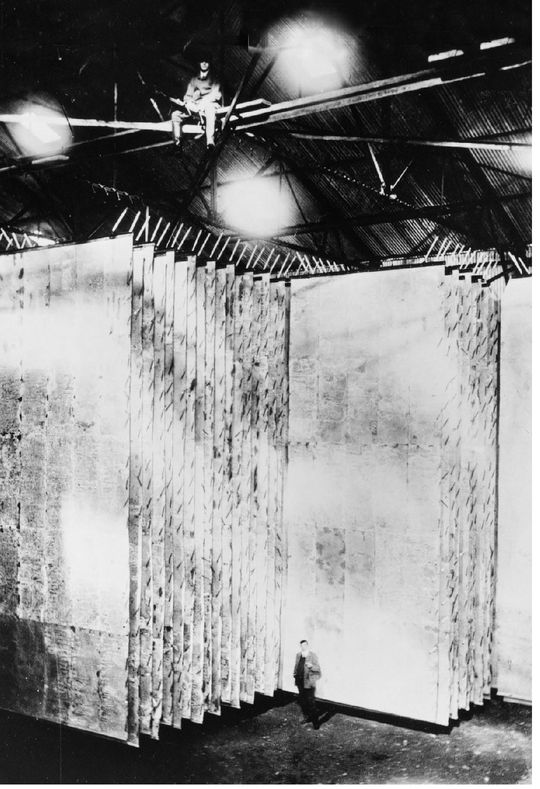

A dramatic illustration of how Marconi’s practical but anachronistic technology grew to outlandish proportions. These are the gigantic power packs of his transmitter at Clifden, on the west coast of Ireland, built before he discovered there were more efficient ways to send signals across the Atlantic.

Other books

Casino Infernale by Simon R. Green

Fleeced by Julia Wills

The Assassin Game by Kirsty McKay

Living the Charade by Michelle Conder

Finding Dr. Right (Contemporary Medical Romance) by Lisa B. Kamps

Indelible by Karin Slaughter

Do Cool Sh*t by Miki Agrawal

A Twist in the Tale (2011) by Comley, Mel

Whispers from Yesterday by Robin Lee Hatcher

Fall Gently (Red Light: Silver Girls series) by Debra Kayn