Silent Witnesses (26 page)

Authors: Nigel McCrery

On August 14, 1751, Francis Blandy finally died. Knowing that she was already under suspicion, Mary offered the footman £500 if he would help her run away to France. He refused and she was forced to flee on her own. It wasn't long, however, before the circumstances of Blandy's death became common knowledge. A hue and cry went up and, despite her best efforts, Mary was captured and brought back to the village. Cranstoun also ran for France when he heard of the situation. He made it but died there in poverty a few months later.

How we interpret Mary's actions depends on whether we believe she knew that the powder was poisonous all along. If she didn't know, then it is reasonable to think she fled the room when her father asked if she was poisoning him because she feared he would be angry at being administered mood-lightening powder without permission. When told by the doctor that the powder was harmful, she immediately disposed of it. If she was administering the poison in full knowledge, then it is clear she fled from guilt, continued to give her father the powder until he was dying, and then destroyed the evidence. However, it is perhaps harder for us to believe that she was totally ignorant of what was happening.

While Mary was awaiting trial she learned that, far from her

father leaving £10,000 behind, he had left less than £4,000. This was the real reason that he had not wanted her to marry; he couldn't afford the £1,000 dowry. Since Cranstoun had been interested in Mary on account of the supposed £10,000 she stood to inherit, the sad fact is that if Francis Blandy had been more honest about his situation and explained his predicament to Mary, tragedy might well have been averted. He died for a nonexistent fortune. Perhaps that is why he found it so easy to forgive her.

Mary was tried for murder at Oxford Assizes on March 3, 1752. The trial took only a single day. As well as the testimony of Susan Gunnel regarding the white powder she had found at the bottom of the cooking pot, a cook gave evidence that she had seen Mary throw the letters and white powder onto the kitchen fire. A postmortem had been conducted on Francis Blandy, and although his organs could not be definitively tested for arsenic (as such a test had not yet been devised), the well-preserved state of them led several doctors to suggest that arsenic poisoning was a possible cause of death. An examination of the powder that the cook saved from the fire confirmed that it was indeed arsenic. Admittedly their method for establishing this was somewhat rudimentary: they applied a red-hot poker to the sample and smelled the resulting vapor. Still, they were convinced. Mary was found guilty and hanged on April 6, 1752. Dressed all in black with her hands tied behind her back with a black ribbon, she asked the hangman not to hang her too high for the sake of decency.

Even though medical testimony helped convict her, the reason that Mary was caught was largely because she was not careful enough to conceal what she was doing. Had the evidence of the powder not been discovered by the servants, it is unlikely that

anyone could have proved that arsenic had been used to kill Francis Blandyâas we have seen, there were no reliable scientific techniques for detecting the presence of the poison. It was a German Swedish chemist called Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1742â1786) who changed that.

Scheele was already well known in scientific circles, having discovered seven different acids (in actual fact he discovered many more than this, but always seemed to be beaten to publication by someone else, hence his nickname, “Hard Luck Scheele”). In 1775 he made the further discovery that it was possible to make an acid by heating arsenic trioxide, “white arsenic” powder, in a solution of nitric acid and zinc. This created a dangerous gas that smelled of garlicâarseniuretted hydrogen, or arsine. This discovery meant that Scheele could now perform a postmortem test to determine if someone's stomach contained arsenic trioxide.

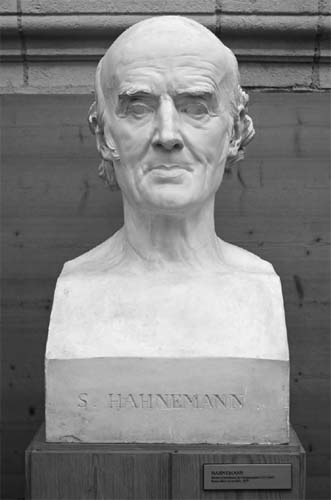

The German physician Samuel Hahnemann (1755â1843) is best known for developing the system of alternative medicine known as homeopathy. However, in 1785 he also found a method of detecting the presence of arsenic that differed from that developed by Scheele. Hahnemann discovered that when sulphuretted hydrogen gas (the gas that smells like rotten eggs) is bubbled through an acidified arsenic solution, the result is a yellow deposit: arsenic trisulphide. In Hahnemann's test a sample that was suspected of containing arsenic could therefore be tested in two simple steps. One: dissolve the sample in nitric acid. Two: bubble sulphuretted hydrogen through the solution. If a yellow sulphide appears, arsenic is present in the sample.

And in 1787, Johann Daniel Metzger (1739â1805), a professor of medicine at the University of Berlin, discovered an even easier way to confirm the presence of arsenic. He found that when a suspect material was heated along with charcoal, arsenious oxide would vaporize if it were present, and that it would leave a shiny black deposit on a porcelain plate (known as an “arsenic mirror”) if you held it above the heated mixture.

Samuel Hahnemann, who invented a simple test for the detection of arsenic and thereby paved the way for the arrest of many poisoners.

However, while all these discoveries were obviously important steps forward, they were only really theoretically useful. As yet there was still no way to apply these tests in a practical, forensic context. This problem was solved in 1806 by Dr. Valentine Rose of the Berlin Medical Faculty. He cut up the stomach of a victim who had allegedly been poisoned with arsenic and boiled it in water. He then filtered the resulting liquid and treated it with nitric acid. This would have the simultaneous effect of ridding the mixture of any remaining traces of flesh and converting any acid in the mixture into arsenious acid. Following this, he used potassium carbonate and calcium oxide, which would turn arsenious acid to arsenic trioxide. He was then able to perform Metzger's test to confirm the presence of arsenicâalthough it could have easily been detected through any one of the various means we have already mentioned.

We now come to one of the great unsung heroes of crime detection, the chemist James Marsh (1794â1846), who eventually held the post of Ordnance Chemist at the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, southeast London, during the 1830s. In 1829 he had worked as Michael Faraday's assistant and had apparently shown a great deal of promise as a scientist. It was a few years after this, in 1832, that Marsh was called to test a powder found in the organs of George Bodle, an eighty-year-old man with a vast fortune of £20,000 (about £2 million today). The prosecution believed this powder was responsible for his death.

Bodle was a farmer from Plumstead near London and was

ordinarily a vigorous and healthy man. However, one day he was suddenly taken ill after drinking his morning coffee. He began vomiting, suffered stomach cramps, and subsequently died. The local justice of the peace, Mr. Slace, began to investigate the matter. He soon found out that Bodle was not a popular man with his family; he was dictatorial and prone to fits of violence. It was also noted that nobody in the family seemed upset at his death. There were rumors circulating that Bodle's grandson John had wanted him dead, and the sooner the better. Given these suspicious circumstances, Slace asked Marsh to test the contents of George Bodle's stomach, and the coffee, in order to establish whether or not arsenic could have been the cause of death. Marsh used Scheele's test, which quickly revealed the presence of arsenic in the coffee. Likewise, when the stomach contents were tested, a yellow sulphide precipitate confirmed that arsenic was present. A local chemist also testified that he had sold John Bodle arsenic trioxide, while a maid who worked on the farm reported that John Bodle had said he wanted his grandfather dead so he could inherit his money. The results from Marsh's tests combined with the witnesses' statements seemed to confirm John Bodle's guilt. It was an open-and-shut case.

However, at John Bodle's trial in Maidstone in December 1832, he was surprisingly found not guilty. Part of the reason for this was that the samples of yellow arsenic trisulphide that Marsh had recovered from the coffee and stomach contents had deteriorated by the time of the trial. The jury therefore had to acquit on the grounds of reasonable doubt, since there was no incontrovertible proof of the presence of arsenic. Many years later John Bodle, who in the intervening time had been deported to the colonies for fraud, finally admitted to murdering his

grandfather, though too late for anything to be done about it.

At the time, Marsh was stung by his failure to secure a conviction and resolved that he would pick up where Scheele had left off. He wanted to create a test that could not only infallibly detect the presence of arsenic, but which would also be able to be understood by a lay jury. The method he eventually developed involved adding the sample matter to a solution of hydrochloric acid and zinc, which would create arsine gas if arsenic was present, as well as hydrogen gas generated from combining the zinc and acid. If he trapped this gas, directed it through a tube, and then ignited it, a silvery black stain would form on a porcelain

Plate held

in front of the tube if arsine gas was presentâmetallic arsenic. The test did prove to have its drawbacks, though; if antimony (another poisonous substance) was present, it would also form a black deposit under this test. However antimony, unlike arsenic, dissolves in sodium hypochlorite, so there was a way of differentiating the two if necessary.

Marsh's test proved to be so sensitive that quantities of arsenic as small as one fifth of a milligram could be detected. He first published the details of it in

The Edinburgh Philosophical Journal

in 1836. Marsh gave us the first really practical and reliable test for the presence of arsenic. However, he died in 1846, at the age of fifty-two, leaving his wife and children destitute. A sad end to such a bright and influential career.

In 1841 a German chemist named Hugo Reinsch (1809â1884) published a new arsenic test, which required far less skill than the Marsh test. Because of its simplicity, it promised to provide far more accurate results when carried out by less experienced chemists. For the Reinsch test, a sample of the suspected liquid was mixed with hydrochloric acid. Then a polished copper foil

strip was placed into the mixture. If any arsenic was present in the sample, it would react with the hydrochloric acid and leave a grey stain on the copper foil. But although simpler and quicker to perform, this method soon proved to have its own drawbacks, as demonstrated in the trial of Thomas Smethurst.

On May 2, 1859, Smethurst, a retired surgeon in his late forties, was arrested for attempted poisoning. A few years earlier he had moved into a boarding house in Bayswater, London. It was there that he met Isabella Bankes, a fellow lodger. Bankes was a wealthy, independent woman, also in her forties. It did not take long for Smethurst to begin a passionate affair with her. He soon left his wife to begin a new life with Bankes in Richmond, and on December 9, 1858, Smethurst and Bankes were married, despite Smethurst still being bound by his previous vows.

In March 1859, only a few months after their marriage, Bankes became violently ill, exhibiting symptoms such as high fever, vomiting, and diarrhea. She was treated by several doctors, and when her condition did not improve, they became suspicious and sent samples of her bodily excretions to be examined. These were tested by Alfred Swaine Taylor, the widely respected English toxicologist. He found what he believed to be a metallic poison in one sample, and Smethurst was arrested on suspicion of poisoning. Unfortunately it was too late to help Bankes and she died soon after Smethurst's arrest.

After Bankes's death, Taylor carried out further tests, including on medicine bottles found in the lodgings she shared with Smethurst. One medicine bottle containing chlorate of potash was also found to contain traces of arsenic. Taylor deduced that Smethurst had poisoned the medicine so he could administer it to Bankes undetected. Smethurst was immediately charged

with murder. However, Bankes's postmortem failed to find any trace of arsenic in her body, nor did further tests on bodily fluids that had been collected when she was alive.

Confused, Taylor tried to think of another explanation. It was known that copper could sometimes contain arsenic impurities. Taylor suddenly realized that the copper he had used during the Reinsch test was not pure enough, and that arsenic impurities in it had reacted with the hydrochloric acid used in the test to create the telltale grey stain. Smethurst's trial was already under way, and despite Taylor alerting the court and the jury to his mistake, it continued, as the magistrate believed the “metallic poison” found in the original sample from Bankes was enough evidence to prove Smethurst's guilt. Smethurst was found guilty of murder. However, after vociferous protest from both the public and medical professionalsâincluding petitions to the Home Officeâhis sentence was lifted. Commentators on the case highlighted evidence that seemed to have been ignored during the trial. Bankes was prone to fits of illness throughout her life, including extended periods of vomiting. Not only that, but the medicine she received from doctors in fact contained mercury, which might well explain the metallic poison that was believed to be present in her fluid samples. It seems likely that she simply died of natural causes, a consequence of her chronic poor health.