Silent Witnesses (24 page)

Authors: Nigel McCrery

In modern criminal investigations, the careful handling of evidence is essential forensic practice. The forensic investigator shown here uses gloves, a swab, and a sterile evidence bag to ensure that key materials do not become contaminated in the course of being removed from the crime scene.

Of all the cases I have ever read about, that of Buck Ruxton is perhaps one of the most intriguing and disturbing. It was solved by yet another extraordinary forensic scientist, Professor John Glaister Jr. (1892â1971). During the First World War, Glaister served in Palestine with the Royal Army Medical Corps before returning home to Glasgow in 1919. There he became an assistant in Glasgow University's Department of Forensic Medicine, where his father (John Glaister Sr., also a prestigious forensic scientist) was regius professor. Following this, Glaister Jr. spent three years in Cairo as a professor of forensic medicine at the University of Egypt, where he had the unique opportunity to examine mummified bodies. He succeeded his father as regius professor in 1931. Glaister was in considerable demand as an expert witness, with his most celebrated case undoubtedly being that of Buck Ruxton.

On September 19, 1935, a woman named Susan Haines Johnson, who was visiting from Edinburgh, decided to take an afternoon walk near the town of Moffat in Dumfriesshire, Scotland. As she was crossing the aptly named Devil's Bridge, over a little stream called Gardenholme Linn, she noticed a bundle of some kind trapped against a rock in the stream. Looking more closely, she realized to her horror that there seemed to be a human arm sticking out of one side of it. She immediately hurried home to the house of her brother Alfred, who called the police.

Inspector Strath and Sergeant Sloane of the Dumfriesshire Constabulary began the investigation. When a search of the immediate area was conducted, several more parcels were found along the banks of the stream, all of which contained human remains. These included an armless torso, a thighbone, legs,

pieces of human flesh, and two upper arms wrapped in a woman's blouse and in newspaper. When opened, the latter turned out to be the

Sunday Graphic,

dated September 15, 1935. Two severed heads were also discovered, one of which was wrapped in a child's romper.

The following day Glaister arrived at the scene, along with his colleague Dr. Gilbert Millar. Almost immediately they knew that the dismemberment of the bodies had been carried out by someone who knew what he was doing; the dissection was careful and accomplished. A knife had been usedâunless a person understands how the human body works, it is almost impossible to cut a body up using a knife rather than a saw. Additionally, the flesh had been peeled from the faces in a clear attempt to conceal the identity of the victims. The fingers had all been sliced off at the terminal joint to prevent fingerprinting. Likewise all the teeth had been removed, rendering dental records useless. It later transpired that any marks on the bodies such as birthmarks and scars from operations or injuries had also been carefully removed.

The remains were taken to the anatomy department of the University of Edinburgh and treated to destroy the maggots that had infested them, and to prevent any further decomposition. They were placed in a formalin solution in order to preserve them as much as possible. Glaister and Millar, along with Sydney Smith and James Brash, professors of forensic medicine and anatomy respectively, now began to work on the remains. They were faced with an unenviable task: trying to reconstruct seventy pieces of human body into their original complete forms and then identify them. A macabre jigsaw puzzle indeed.

Their first task was to work out which pieces belonged with each other and to separate them out accordingly. They then began the process of putting them back into a semblance of their original shape. In so doing, they established that one of the bodies was six inches taller than the other, which speeded up the process considerably. They found that they had most of the taller person, but that the trunk of the shorter person was still missing. They also found a large eye, which clearly did not come from either of the victimsâGlaister assumed that it had belonged to some kind of animal and had accidentally been mixed in with the bodies of the victims.

Although a lot of questions still remained about who these people were, more body parts kept being discovered as the river was combed, which gave valuable new information. Two hands where the fingertips had not been cut off were discovered. By soaking these in hot water, Glaister was able to get a first-class set of prints off them. At first it had been thought that the smaller remains were those of a male, but as more pieces were recovered, the team eventually found three breasts, indicating that both bodies must be female.

They now needed to determine the age of the two individuals. Glaister did this through looking at the sutures of the skulls. Sutures are the fibrous joins between the different sections of bone that make up the skull. The process of them sealing up begins in infancy and typically finishes at around the age of forty. In the case of the skull of the smaller person, the sutures remained unclosed; in that of the larger person they were almost completely closed. This meant that the smaller person was certainly under thirty, while the larger person was approximately forty. Further examination of the smaller skull revealed that the

victim's wisdom teeth had not yet emerged, which almost certainly meant she was in her early twenties.

The next job was to establish a cause of death for both women. It transpired that the taller woman had sustained five stab wounds to the chest and had a number of broken bones, as well as numerous bruises. The hyoid bone in her neck was broken, suggesting that she had been strangled before the other injuries were inflicted; someone had wanted to make absolutely certain that she was dead. The shorter woman showed signs of having been battered with some kind of blunt instrument, though the swelling of the tongue was also consistent with asphyxia.

While Glaister and his team were working on the remains, the police were out searching for the culprit. The

Sunday Graphic

from September 15, which the arms had been wrapped in, was an extremely important lead. Not only did it help to establish when the killings had taken placeâit also gave a clue as to where. It was a “slip” edition, meaning it was a special issue for an event of local importance and had been circulated only in that area. This particular edition had been published to celebrate the Morecambe festival and had only been sold there.

Now chance offered a helping hand to the investigation. It so happened that the chief constable of Dumfriesshire read about the disappearance of a woman named Mary Jane Rogerson, a nursemaid at the home of a Dr. Buck Ruxton. She had gone missing from Lancaster, which lies close to Morecambe. A telephone call to the chief constable of Lancaster revealed that Ruxton's wife had also gone missing at the same time. This seemed extremely suspicious, and detailed descriptions of both women were quickly forwarded to the Dumfriesshire constabulary.

Buck Ruxton was Parsi, born in Bombay on March 21, 1899. He obtained his Bachelor of Surgery at the University of Bombay and served with the Indian Medical Service in Baghdad and Basra. His original name was Bukhtyar Rustomji Ratanji Hakim, but he later changed it when he moved to the United Kingdom to set up his practice in Lancaster in 1930. Ruxton was respected as a GP, proving popular with his patients. He also regularly displayed generosity, forgoing fees for impoverished patients. His image was that of a family man, and he lived comfortably at 2 Dalton Square with his wife Isabella and their three children.

Jessie Rogerson, who lived in Morecambe and was Mary's stepmother, was brought in by the police to see if any of the clothing that been found with the bodies was familiar to her.

She was distraught, quickly recognizing the blouse as one belonging to her stepdaughter, and pointing out a repair that she herself had previously made to it. The child's romper which had been used to wrap one of the heads was identified by a Mrs. Holmes of Grange-over-Sands as one that had been given to the Ruxtons some time before. Jessie Rogerson had suggested her as a lead because Mary had vacationed with her that same year, and Mrs. Holmes had given her the romper for her children. The unpleasant fact of the matter was that the police now had very good reason to link Buck Ruxton to the case. Being a medical man, he also had the kind of practical anatomical knowledge that the killer must have had to dismember the bodies. The police acted quickly and arrested him.

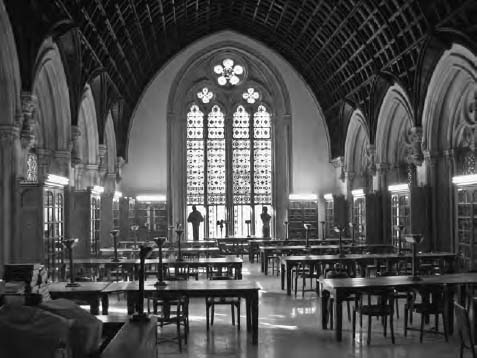

The library at the University of Mumbai (formerly Bombay) where Ruxton studied.

The last time Isabella had been seen alive was on Saturday, September 14, when she and her sisters had gone to Blackpool, spending time there enjoying the lights before returning home that night. It transpired that on the following Monday, Ruxton had called his cleaner and said that her services would not be required since his wife had gone on a trip to Edinburgh. He did though, rather bizarrely, invite a Mrs. Hampshire over, asking if she could help him clean up the house to get it ready for the decorators who were due the following week. She would later testify that she helped him to dispose of bloodstained carpets and clothing by burning them outside in the garden. Quite why she did not consider this suspicious at the time is unclearâperhaps she naively thought blood must be an occupational hazard of being a doctor. Other witnesses also gave evidence that fires were seen burning behind the house for several days. When the police searched the property, human flesh was found in the waste pipes and drains leading from the bath, and

bloodstains were discovered on the carpet on the stairs and on the bathroom walls and floor. When the charred remains outside were searched, several pieces of cloth were recovered which were identified as having belonged to Mary Rogerson.

It seemed certain that the police had their man, but they still needed to positively identify the bodies in their possession as being Mary and Isabella. They were able to do so through several ingenious forensic techniques. Firstly, fingerprints that they had managed to take from one of the bodies were found to match prints they were able to lift from several items in the house that Mary touched on a regular basis.

Now came a first in the history of forensics. The team managed to get hold of photographs of the two women, a studio shot of Isabella and two poorer-quality images of Mary. The skulls were cleaned of any remaining tissue and then photographed from various angles to match the angles shown in the photographs as closely as possible. When these new photographs were blown up to the same size and superimposed over the original photographs of Mary and Isabella, they matched perfectly (see

Plate 11

).

And finally, in another ingenious first, Dr. Alexander Mearns of the Institute of Hygiene at the University of Glasgow was able to establish, through observing the life cycle of the maggots that infested the remains, that the two victims had been killed at approximately the same time that Isabella and Mary had last been seen alive. Never before had entomology been applied forensically like this.

With this weight of evidence against him, it is perhaps unsurprising that Ruxton was found guilty of murder, though he protested his innocence to the last. He was executed at Strangeways Prison on May 12, 1936. It is believed his motive

for the murder must have been jealousy and the belief that Isabella was being unfaithful to him. The two were known to have a tempestuous relationship, and the police had been called out to the property as a result of their arguments on more than one occasion. Poor Mary Rogerson was probably just in the wrong place at the wrong time and witnessed something that she should not have. Ruxton had used his expert knowledge to good effect in trying to conceal the identities of his victims through systematic mutilation, but this was not enough to eradicate all the information that the remains were able to impart.

While the natural impulse of any person when confronted with a dead bodyâparticularly one that has been horribly disfigured or dismemberedâis to recoil, when a violent crime is being scrutinized, a corpse often represents the focal point of the investigation. When a body can provide so many different forms of valuable evidence that may bring a killer to justice, a forensic scientist cannot afford to be squeamish.

Poisons

A poison in a small dose is a medicine, and a medicine in a large dose is a poison.

Alfred Swaine Taylor, English toxicologist (1806â1880)

P

oison was described by the Jacobean writer John Fletcher as “the coward's weapon”âa stealthy way of killing that leaves no mark of violence on the body and that might even be mistaken for illness. Particularly in the past, poisoning is often associated with repressed and marginalized members of societyâthat is, those who did not have recourse to other methods. For this reason it was also frequently associated with women; a wife might not have been able to physically overpower her husband, but poison gave her a less direct way to end his life. From a forensic perspective, poisons present their own problems and challenges, which we will explore in this chapter. First, however, it is perhaps worth taking a brief look at poisoning throughout history, and tracing the gradual acquisition of knowledge about the practice.