Sisters in Spirit: Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists (6 page)

Read Sisters in Spirit: Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists Online

Authors: Sally Roesch Wagner

The Untold Story

I did not set out to look for this connection, this link between early suffragists and Native peoples. In truth, if someone had suggested it to me when I taught my first women’s studies class in 1969, I would have scoffed at yet one more “romantic Indian” story. I had a single question, basic to feminist history:

How did the radical suffragits come to

their vision, a vision not of Band-Aid reform but of a reconstituted world completely transformed?

Surely I should know the answer—after all, I had helped found one of the nation’s first women’s studies programs (at California State University, Sacramento) and received one of the first doctorates for work in women’s studies (from the University of California, Santa Cruz). I was credentialed but I was baffled.

How did the radical suffragits come to

their vision, a vision not of Band-Aid reform but of a reconstituted world completely transformed?

Surely I should know the answer—after all, I had helped found one of the nation’s first women’s studies programs (at California State University, Sacramento) and received one of the first doctorates for work in women’s studies (from the University of California, Santa Cruz). I was credentialed but I was baffled.

For twenty years I had immersed myself in the writings of early United States women’s-rights activists Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826- 1898) and Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902), yet I could not fathom how they dared to dream their revolutionary dream. Living under the ideological hegemony of nineteenth-century United States, these women had no say in government, religion, economics, or social life. Whatever made them think that human harmony, respect for women’s lives, and equal rights for women were achievable? Surely these white women, living under conditions they likened to slavery, did not receive their vision in a vacuum.

Certainly there was a European foundation for American feminism. Gage, regarded as “one of the most logical, fearless, and scientific writers of her day,” maintained that European women, along with their male supporters, had waged a four-hundred-year struggle for woman’s rights.

1

She asserted this past came to the forefront during the American Revolution:

1

She asserted this past came to the forefront during the American Revolution:

When the American colonies began their resistance to English tyranny, the women—all this inherited tendency to freedom surging in their veins—were as active, earnest, determined and self-sacrificing as the men...

2

These active revolutionary women saw the struggle as one that could extend the principles of democracy to all groups—including slaves and women. Gage noted that Mercy Otis Warren, Abigail Smith Adams, and Hannah Lee Corbin all “manifested deep political insight” about women’s rights. During the formation of the government, Abigail Adams advised her husband John to “be more generous and favorable to [women] than your ancestors.” She cautioned, “Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands,” or, Abigail Adams warned, “we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.”

3

“Thus did the Revolutionary Mothers urge the recognition of equal rights when the Government was in the process of formation,” Gage observed.

4

3

“Thus did the Revolutionary Mothers urge the recognition of equal rights when the Government was in the process of formation,” Gage observed.

4

The forefathers looked with disdain on anything British as they formed their new government—until it came to forcing women into their place. Then the men looked to England for their model. The European tradition of church and law placed women in the role of property, British historian Herbert Spencer maintained. “Our laws are based on the all-sufficiency of man’s rights, and society exists today for woman only in so far as she is in the keeping of some man,” Gage quoted Spencer.

5

5

Abigail Adams feared—accurately, it turned out—that English common law, (having been recently codified by Blackstone), would provide the basis for family law as the states solidified their laws after the revolution. It marked a decided set-back for women. Woman’s “very being or legal existence was upended during marriage, or at least, incorporated or consolidated into that of the husband, under whose wing, protection and cover, she performs everything,” Blackstone had written. “The two shall become one and the one is the man,” the church proclaimed in canon law, and common law echoed the proclamation. Abigail Adams maintained that marriage under common law robbed woman of her rights and created conditions that encouraged men to act tyrannically.

At least one founding father joined the Revolutionary-era feminists. Tom Paine penned what was probably the first plea for equal rights published in the United States. Influenced by Mary Wollstonecraft, British women’s rights advocate and author of the 1792 feminist classic,

Vindication of the Rights of Women,

Paine boldly began his 1775 essay in the

Pennsylvania Magazine

with the assertion that man is the oppressor of woman.

6

Vindication of the Rights of Women,

Paine boldly began his 1775 essay in the

Pennsylvania Magazine

with the assertion that man is the oppressor of woman.

6

Calls for women’s rights during the Revolution, however, were ignored. Once they had cemented power, the United States revolutionaries placed women in a position of political subordination more severe even than that of the colonial period.

7

7

Under the European-inspired laws adopted by each state after the revolution, a single woman might own property, earn a living, and be economically independent but, upon uttering the marriage vows, she lost control of her property and her earnings. She also gave away all rights to the children she would bear. Offspring became the “property” of the father who could give them away or grant custody to someone other than the mother, in the event of his death. With the words “I do,” a woman literally gave up her identity. Legally, the woman lost her name, any right to control her own body, and to live where she might choose. A married woman could not make any contracts, sue, or be sued; she was considered dead in the law. Wife-beating was not against the law; neither was marital rape.

Women’s rightsThe concept of women’s rights could not be easily incorporated into Euro-Christian tradition. Rather, feminism challenged the very foundation of Western institutions, Gage beHeved—especially that of religion.

8

8

As I look backward through history I see the church everywhere stepping upon advancing civilization, hurling woman from the plane of “natural rights” where the fact of her humanity had placed her, and through itself, and its control over the state, in the doctrine of “revealed rights” everywhere teaching an inferiority of sex; a created subordination of woman to man; making her very existence a sin; holding her accountable to a diverse code of morals from man; declaring her possessed of fewer rights in church and in state; her very entrance into heaven made dependent upon some man to come as mediator between her and the Savior it has preached, thus crushing her personal, intellectual, and spiritual freedom.

9

“No rebellion has been of like importance with that of Woman against the tyranny of Church and State”

Matilda Joslyn Gage

Discontent came to a head for radical women’s rights reformers when they realized in the late 1880s that their hard labor of forty years had not resulted in woman’s equality in the church, state, work place, or family. The United States Supreme Court had ruled that the right to vote was not guaranteed to them. Still seen as the source of evil by the church because of Eve’s original sin, women continued to be, as Gage called them, the “great unpaid laborers of the world,” the virtual slave of the household and, in the few occupations open to them, paid only half the wages men received.

Reformers who had spent their whole lives working unsuccessfully to change woman’s condition began to realize the depth of the roots of oppression. Certainly they must have had doubts. Could women’s position be natural or “God-ordained,” as the enemies of freedom constantly told them? Both Stanton and Gage’s vision became deeper and broader as their successes failed to materialize.

Gage expressed it this way:

During the ages, no rebellion has been of like importance with that of Woman against the tyranny of Church and State; none has had its far-reaching effects. We note its beginning; its progress will overthrow every existing form of these institutions; its end will be a regenerated world.

10

How were these women able to see from point A, where they lived—corseted and ornamental non-persons in the eyes of the law—to point C, the “regenerated world” Gage predicted, in which all repressive institutions would be destroyed? What was point B in their lives, the real and visible alternative that drove their feminist spirit—not a Utopian pipe dream but a living example of equality?

Corseted and ornamental non-persons in the eyes of the law.

Then it dawned on me. I had been skimming over the source of their vision without even noticing it. My own stunningly deep-seated presumption of white supremacy had kept me from recognizing what these prototypical feminists kept insisting in their writings. They believed women’s liberation was possible because they knew liberated women, women who possessed rights beyond their wildest imagination: Haudenosaunee women.

Gage and Stanton, major theorists of the woman suffrage movement’s radical wing, became increasingly disenchanted with the inability and unwillingness of Western institutions to change and embrace the liberty of not just women, but all disfranchised groups. They looked elsewhere for their vision of the “regenerated world” and they found it—in upstate New York. They became students of the Haudenosaunee and found a cosmological world view they believed to be superior to the patriarchal, white-male-dominated view prevalent in their own nation.

Once I understood the connection, I came to realize it was everywhere—right where I hadn’t seen it before. The more evidence I uncovered of this indelible Native influence on the vision of early United States feminists, the more certain I became that, previously, I had been dead wrong. Like most historians do, I had assumed that the story of feminism began with the “discovery” of America by white men, or the political revolution staged by the colonists—that there was no seed of feminism already in American soil when the first white settlers arrived. Without realizing it, I had assumed that white people had imported the germ of the idea of woman’s rights and that was the end of the story. My eyes and ears, I realized, certainly needed the clearing Ray Fadden advised in his “Fourteen Strings of Purple Wampum to Writers about Indians.”

A Vision of Everyday JusticeThe European invasion of America resulted in genocide. That is the most important story of contact. But it is not the only one. While Europeans concentrated on “Christianizing and civilizing,” relocating and slaughtering Indians, they also signed treaties, coexisted with and learned from them. Regular trade, cultural sharing, even friendship between Native Americans and EuroAmericans transformed the immigrants. Perhaps nowhere was this social interaction more evident than in the towns and villages in upstate New York where Matilda Joslyn Gage lived, Elizabeth Cady Stanton grew up, and Lucretia Mott visited. All three of these leading suffragists knew Haudenosaunee women, citizens of the Six Nations Confederacy that had established peace among themselves long before Columbus arrived at this “old” world.

Stanton, for instance, sometimes sat across from Oneida women at the dinner table in Peterboro, New York, during frequent visits to her cousin, the radical social activist Gerrit Smith.

11

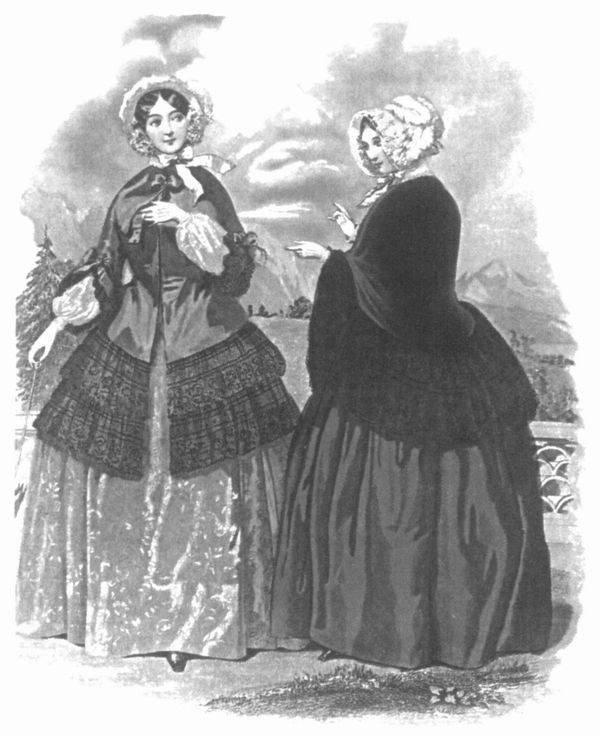

Smith’s daughter (also named Elizabeth) was among the first to shed the twenty pounds of clothing that fashion dictated should hang from any fashionable woman’s waist, usually dangerously deformed from corseting. The reform costume Elizabeth Smith adopted (named the “Bloomer” after the newspaper editor who popularized it) promised the health and comfort of the loose-fitting tunic and leggings worn by Native American friends of the two Elizabeths.

11

Smith’s daughter (also named Elizabeth) was among the first to shed the twenty pounds of clothing that fashion dictated should hang from any fashionable woman’s waist, usually dangerously deformed from corseting. The reform costume Elizabeth Smith adopted (named the “Bloomer” after the newspaper editor who popularized it) promised the health and comfort of the loose-fitting tunic and leggings worn by Native American friends of the two Elizabeths.

Other books

Kayla's Cowboy Fantasy (Delta of Venus Inc.) by Vincent, Verena

CougarHeat by Marisa Chenery

The Violet Hour by Miller, Whitney A.

Gavin (A Redemption Romance #3) by Anna Scott

Sharpe's Revenge by Bernard Cornwell

Millie and the Night Heron by Catherine Bateson

Office of Innocence by Thomas Keneally

Miras Last by Erin Elliott

Renegade by Antony John

The Traveler's Companion by Chater, Christopher John