Sisters in Spirit: Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists (7 page)

Read Sisters in Spirit: Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists Online

Authors: Sally Roesch Wagner

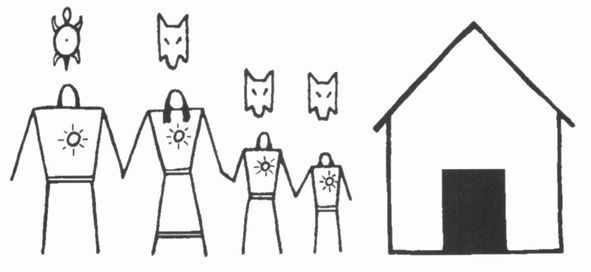

Bloomers on an American woman. Carolyn Mountpleasant, a Seneca woman, in traditional dress.

In 1853 Gage worked on a committee headed by

New York Tribune

editor Horace Greeley to document the woefully few jobs open to white women.

12

Meanwhile she knew nearby Onondaga women who farmed corn, beans, and squash—nutritionally balanced and ecologically near-perfect crops called “the Three Sisters” by the Haudenosaunee.

13

New York Tribune

editor Horace Greeley to document the woefully few jobs open to white women.

12

Meanwhile she knew nearby Onondaga women who farmed corn, beans, and squash—nutritionally balanced and ecologically near-perfect crops called “the Three Sisters” by the Haudenosaunee.

13

Lucretia Mott and her husband, James, were members of the Indian Committee of the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of the Society of Friends. From the 1790s on, these Quakers sent missionaries among the Seneca, educating them and supporting them against unscrupulous land speculators. During the summer of 1848 the Motts visited Cattaraugus where they witnessed women exercising equal authority in discussion and decision-making while the Seneca nation changed its governmental structure. Lucretia watched as the Native women planned the strawberry ceremony in a most non-Christian tradition of women’s spiritual leadership. With her feminist vision fired by her first-hand experience of women’s political, spiritual, social, and economic authority, Mott traveled from the Seneca nation to nearby Seneca Falls, where she and Stanton called the world’s first woman’s rights convention in July.

Lucretia Mott’s feminist vision was fired by her first-hand experience of women’s political, spiritual, social and economic authority, in the Seneca community.

These suffragists regularly read newspaper accounts of everyday Iroquois activities: a condolence ceremony to mourn a chief’s death and to set in place a new one; the sports scores when the Onondaga faced the Mohawks at lacrosse; a Quaker council called to ask Seneca women to leave their fields and work in the home (as the Friends said God commanded but as Mott opposed). Newspaper readers in New York also read interviews with white teachers who worked at various Indian nations testifying to the wonderful sense of freedom and safety they felt, since Indian men did not rape women. These front-page stories admonished big-city dandies to learn a thing or two from Native men’s example, so that white women too could walk around any time of the day or night without fear. Rev. M. F. Trippe, long a missionary on the Tonawanda, Cattaraugus and Alleghany reservations, told a New York City reporter:

Tell the readers of the

Herald

that ... they have a sincere respect for women—their own women as well as those of the whites. I have seen young white women going unprotected about parts of the reservations in search of botanical specimens best found there and Indian men helping them. Where else in the land can a girl be safe from insult from rude men whom she does not know?

14

In the United States, until women’s rights advocates began the painstaking task of changing state laws, a husband had the legal right to batter his wife. A North Carolina court ruled in 1864 that the State had no business meddling in wife battering cases unless “permanent injury or excessive violence” was involved. The batterer and his victim should be left alone, the court determined, “as the best mode of inducing them to make the matter up and live together as a man and wife should.”

15

Suffragists knew that wife battering was not universal, living as neighbors to men of other nations whose religious, legal, social, and economic concept of women made such behavior unthinkable. To Stanton, Gage, Mott, and their feminist contemporaries, the Native American principles of everyday decency, nonviolence, and gender justice must have seemed the Promised Land.

A Vision of Power and Security15

Suffragists knew that wife battering was not universal, living as neighbors to men of other nations whose religious, legal, social, and economic concept of women made such behavior unthinkable. To Stanton, Gage, Mott, and their feminist contemporaries, the Native American principles of everyday decency, nonviolence, and gender justice must have seemed the Promised Land.

As a feminist historian, I did not at first pay attention to such references to American Indian life because, without realizing it, I accepted the stereotype that Native American women were poor, downtrodden “beasts of burden” (as they were often called in the nineteenth century). I read right past the suffragists’ documentation of Native women’s superior rights without seeing it.

I remembered that in the early 1970s, some feminists flirted with the idea of prehistoric matriarchies on which to pin women’s egalitarian hopes. Anthropologists soon set us straight about such nonsense. The evidence just wasn’t there, they said. But Paula Gunn Allen, a Laguna Pueblo/Sioux author and scholar, believed otherwise:

Beliefs, attitudes and laws such as [the Iroquois Confederation] became part of the vision of American feminists and of other human liberation movements around the world. Yet feminists too often believe that no one has ever experienced the kind of society that empowered women and made that empowerment the basis of its rules and civilization. The price the feminist community must pay because it is not aware of the recent presence of gynarchial societies on this continent is unnecessary confusion, division, and much lost time.

16

Allen’s words opened my eyes, threw into question much of what I thought I knew about the nineteenth-century woman’s movement, and sent me on an entirely new course of historical discovery. The results shook the foundation of the feminist theory I had been teaching for almost twenty years.

A National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship allowed me to replicate the suffragists’ research, and I tracked down Stanton’s and Gage’s citations, poring over books, newspapers, and journals they had read. I visited Onondaga and slowly began to know some of the women.

I sat in the kitchen of Alice Papineau—De-wa-senta—an Onondaga clan mother, on a hot summer day, drinking iced tea as she described the criteria clan mothers use to choose—and depose, if necessary—the male sachem who represents their clan in the Grand Council, a responsibility of which Stanton and Gage were well aware. But neither suffragist had explained the sachem job requirements, which De-wa-senta listed: “First, they cannot have committed a theft. Second, they cannot have committed a murder. Third, they cannot have abused a woman.” And the overriding qualification: the chief needs to have shown that he can take care of a family, behave as a responsible family man, since he will be responsible for the well-being of the larger families of the clan, the nation and the confederacy—through seven generations.

There goes Congress

! I think to myself, followed by a flight of fantasy: What if, in the United States, only women chose governmental representatives, and women alone had the right “to knock the horns off the head,” as Stanton marveled—to oust officials if they failed to represent the needs of the people unto the seventh generation?

! I think to myself, followed by a flight of fantasy: What if, in the United States, only women chose governmental representatives, and women alone had the right “to knock the horns off the head,” as Stanton marveled—to oust officials if they failed to represent the needs of the people unto the seventh generation?

If I am so inspired by De-wa-senta’s words today, imagine how the founding feminists felt as they beheld the Haudenosaunee world.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was called a heretic for advocating divorce laws that would allow women to leave loveless and violent marriages. “What God hath joined together let no man put asunder,” traditional Christianity intoned! She found a model in Haudenosaunee attitudes toward divorce. Stanton informed the National Council of Women in an 1891 speech, a misbehaving Iroquois husband “might at any time be ordered to pick up his blanket and budge.”

17

What must it have meant to Stanton to know of such real-life domestic authority?

A Vision of Radical Respect17

What must it have meant to Stanton to know of such real-life domestic authority?

While early women’s rights activists successfully changed some repressive laws, an ensuing backlash in the 1870s resulted in the criminalization of birth control and family planning, while custody of the children remained the exclusive right of fathers. By the 1890s, Stanton and her daughter, Harriet, began to envision “voluntary motherhood,” the title of a speech Harriet prepared for the 1891 National Council of Women. “Motherhood is sacred—that is, voluntary motherhood,” Harriet declared, “but the woman who bears unwelcome children is outraging every duty she owes the race. ”

18

Mother and daughter presented a revolutionary alternative to the patriarchal family, with women controlling their own bodies and having rights to the children they bore. No utopian dream, body right was a birthright of Haudenosaunee women. Family lineage traditionally was reckoned through mothers; no child was born a “bastard” (the concept didn’t exist). Every child found a loving and welcome place in a mother’s world, surrounded by a mother’s sisters, her mother, and the men whom they married. Unmarried sons and brothers lived in this large extended family, too, until they left home to marry into another matrilineal clan.

18

Mother and daughter presented a revolutionary alternative to the patriarchal family, with women controlling their own bodies and having rights to the children they bore. No utopian dream, body right was a birthright of Haudenosaunee women. Family lineage traditionally was reckoned through mothers; no child was born a “bastard” (the concept didn’t exist). Every child found a loving and welcome place in a mother’s world, surrounded by a mother’s sisters, her mother, and the men whom they married. Unmarried sons and brothers lived in this large extended family, too, until they left home to marry into another matrilineal clan.

Family lineage traditionally was reckoned through the mothers.

Stanton envied how Indian women “ruled the house” and how “descent of property and children were in the female line.” When called a “savage” for practicing natural childbirth, Stanton rebuked her critics by mocking their use of the word, pointing out that Indian women “do not suffer” giving birth. They “step aside the ranks, even on the march and return in a short time bearing with them the newborn child,” she wrote.

19

Thus it was absurd to suppose “that only enlightened Christian women are cursed” by painful, difficult childbirth.

20

19

Thus it was absurd to suppose “that only enlightened Christian women are cursed” by painful, difficult childbirth.

20

In 1875, while serving as president of the National Woman Suffrage Association, Gage penned a series of admiring articles about the Haudenosaunee for the New York

Evening Post

in which she wrote that the “division of power between the sexes in this Indian republic was nearly equal,” while the Iroquois family structure “demonstrated woman’s superiority in power.”

21

Evening Post

in which she wrote that the “division of power between the sexes in this Indian republic was nearly equal,” while the Iroquois family structure “demonstrated woman’s superiority in power.”

21

For white women living in a world where marital rape was commonplace and forbidden by neither church nor state (although the Comstock Law of the 1870s outlawed discussion of it), Native women’s violence-free and egalitarian home life could only have given suffragists sure knowledge that their goals could be reached. Still, they had a long way to go.

Other books

Not Long for This World by Gar Anthony Haywood

Democracy Matters by Cornel West

More Room in a Broken Heart: The True Adventures of Carly Simon by Stephen Davis

A Crack in the Wall by Claudia Piñeiro

JORDAN Nicole by The Courtship Wars 2 To Bed a Beauty

Fire by C.C. Humphreys

Briannas Prophecy by Tianna Xander

The Gallant by William Stuart Long

Trains and Lovers: A Novel by Alexander McCall Smith

Mercenary Road by Hideyuki Kikuchi