Sisters in the Wilderness (36 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

But during these years, Susanna had found a diversion from day-today anxiety. She had a new interest in her life, which provided her with the kind of catharsis that, when she was stuck in the bush, writing had once supplied. She and John were caught up in one of the nineteenth century's more bizarre trends and she was already using the language of the movement. “May better and brighter days be in store for us both,” she wrote to Catharine, when they were both going through a difficult period. “And may we so improve the material present, that it may open the door of the dear spirit land to our weary longing souls.”

Catharine would soon be swept along too in what her sister recognized as a “glorious madness.”

Chapter 15

Rap, Rap, Who's There?

A

s Susanna Moodie sat at her writing desk on a September day in 1855, she heard her Irish servant Jane clattering out of the kitchen to answer a knock at the front door of the Moodies' house on Bridge Street. A few minutes later, Jane stuck her head into the drawing room and announced that a Miss Fox and her cousin were on the front step and would like a word with Mrs. Moodie. Jane had tried to tell them that Mrs. Moodie was busy right now, but Miss Fox had explained that she was leaving Upper Canada the next day and insisted that Jane at least let Mrs. Moodie know they were here.

Jane was astonished to see how fast Mrs. Moodie, who always discouraged social calls, threw down her quill pen and swept past her to greet her visitors. But Susanna had wanted to meet this afternoon's visitor for a long time. Kate Fox was one of the famous Fox sisters. She and her sister Maggie had ignited an extraordinary transcontinental flare of

interest in “spirit adventures” in 1848 when they gave a public demonstration of their psychic abilities. By 1850, the new practice of spiritualism was already claiming an estimated two million adherents across North Americaâa fantastic figure considering that the total population was only twenty-five million. The Fox sisters and their followers claimed to be able to communicate with the spirits of the dead.

The spiritualist “religion” had begun when Maggie, then thirteen, and Kate, twelve, moved with their parents from Upper Canada to northern New York State. Strange sounds began to plague the family at nightâraps and knockings for which there were no obvious causes. The noises always occurred around the girls. Neighbours crowded into the Foxes' cramped parlour to hear the mystery raps. Mrs. Fox insisted that it was a “disembodied spirit” which would answer questionsâthree raps for “yes,” silence for “no.” Next, the “spirits” that the girls attracted extended their conversational range, thanks to an ingenious device invented by the girls' brother David that allowed the spirits to go through the alphabet. When the appropriate letter was reached, the spirits rapped. It was laborious, but it eventually yielded whole sentences.

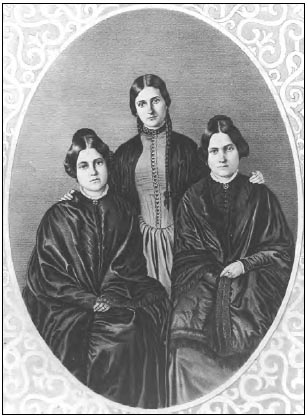

The famous Fox sisters: Maggie, Kate and Leah Fox Fitch. Pretty Kate Fox (centre) was John Moodie's “spiritual muse.”

Soon tales of the Fox girls' strange powers were being passed round at every general store, church hall and drinking house scattered through upstate New York. A public demonstration of their powers was staged in Rochester's splendid Corinthian Hall. Several of the city fathers were deeply sceptical, insisting that the raps must be made either by ventriloquism, a newfangled machine or lead balls sewn into the girls' hems. But each hypothesis was proved wrong, and nobody could furnish any proof that the girls were frauds. Their lucrative careers as spiritualist mediums were launched. They moved to New York City and conducted seances at P. T. Barnum's Hotel; participants paid one dollar each to attend. Big names such as Horace Greeley, editor of the

New York Tribune,

and the author James Fenimore Cooper became converts to their cause. Others quickly jumped on the bandwagon: clairvoyants, hypnotists, trance-speakers, levitationists, table-tappers.

Why did the spiritualist faith catch on with such fury? Why did an essentially mystical movement thrive during an age dedicated to scientific innovation and engineering triumphsâsteam-driven ploughs and railways, gas lamps, suspension bridges and daguerreotypes? In London, the Great Exhibition of 1851 celebrated the glorious products of the Industrial Revolution: mass-produced lace, electroplated silverware, steel surgical implements, Lisle stockingsâall housed in the Crystal Palace, a giant glass house. William Makepeace Thackeray described the show as “A noble awful great love-inspiring gooseflesh-bringing sight ⦠the vastest and sublimest popular festival that the world has ever witnessed.” Agnes and Elizabeth Strickland toured the Crystal Palace and were captivated with its glories. Yet in the midst of all this machine-made production, interest in the occult flourished.

Ironically, it was the ability of spiritualism's supporters to talk about phenomena like the “Rochester rappings” in quasi-scientific terms that gave the activity a bogus scientific credibility. At a time when scientists were investigating invisible sources of energy, spiritualists argued that the Fox sisters were harnessing another kind of unseen force, which could connect souls of this world to those that had already reached the next. Samuel Morse's invention of the electrical telegraph allowed thoughts to travel mysteriously from one location to another; perhaps the Foxes were operating a kind of spiritual telegraph.

Such a theory was particularly tenable in a deeply religious society that believed in a life after death, and nowhere was the population more prone to religious excess in the mid-nineteenth century than in the state of New York. It had experienced so many religious revivals (usually during the cold, dark days between Christmas and spring) that it was known as the “burned-over district”âburned over by Holy Rollers preaching fire-and-brimstone sermons to labourers, storekeepers and farmers assembled in lonely barns. Gothic horrors had an equal appeal for the educated: throughout the 1830s and 1840s, Edgar Allan Poe, master of the Gothic

frisson

, published stories in newspapers up and down the East Coast. The most chilling effects in Poe's tales centre on the blurring of the boundaries between life and death, the “fatal frontier.” The paraphernalia of the Fox sisters' seancesâmysterious rappings, darkened rooms, voices from beyond the graveâcombined the notion of scientific inquiry with both a steadfast belief in the immortality of the soul and the fascination of the occult.

It didn't take long for interest in spiritualism to spill over the border. At the Belleville Mechanics' Institute, Susanna and John regularly heard lectures on “mesmerism, phrenology, biology, phonography, spiritual communication &tc.,” according to Susanna. At first, John admitted, he thought that the “Rochester Knockings” were so “utterly ridiculous and puerile, that I only looked upon it as a money-making scheme.” However, he started to wonder whether spiritualism's success demonstrated God's benevolent interest in their well-being: was it, as he put it,

“a great instrument ordained by God to harmonize the human race”?

By the mid-1850s, newspapers were full of accounts of various phenomena, and there were at least a dozen periodicals devoted exclusively to the subject. Susanna was fascinated by the ghoulish mystery of it all. She pored over books like

Spiritualism,

published in 1853 by Judge John Edmonds and Dr. George T. Dexter of New York, which was supposedly the product of spirit-writing, employing Dr. Dexter as the medium. She also read

Experimental Investigations of the Spirit Manifestations, Demonstrating the Existence of Spirits and Their Communion with Mortals

by Robert Hare, a University of Pennsylvania chemist, and E.W. Capron's

Modern Spiritualism: Its Facts and Fanaticisms; its Consistencies and Contradictions.

As a girl, Susanna had believed in telepathy between friends. As a middle-aged woman, her strong religious faith made her respectful of man's spiritual potential, while her curiosity drove her to dig deeper into these mysterious goings-on. Whenever Catharine came to stay, Susanna discussed spiritualism with her in tones of both awe and amusement. “There is a capital article in the last

Albion

on table turning,” she wrote to her sister in 1852. “I read it twice with infinite glee.”

Catharine was not so sure about the whole business. Her God was a God of nature and beauty, who clothed pastures with flocks of sheep and made the valleys “stand so thick with grain that they laugh and sing.” He was not a God who rocked dining-room tables or produced discordant rappings at the bidding of adolescent girls. But she did like the idea, as she told Ellen Dunlop in a letter, that “one of the offices of the released spirit [of someone who died] may be to watch over and care for those that were united to them by bonds of love or friendship during its sojourn upon earth.”

Susanna had been introduced to Kate Fox on the streets of Belleville in the summer of 1854, when Kate Fox (then living in New York City) was visiting her oldest sister Elizabeth Ousterhoust in the nearby village of Consecon. On that occasion, Susanna recalled, she was “much charmed with her face and manners.” The nineteen-year-old's pale oval face, waist-length dark hair and dark purple eyes beguiled the author.

“She is certainly a witch,” Susanna wrote in a letter to Richard Bentley, “for you cannot help looking into the dreamy depths of those sweet violet eyes till you feel magnetised by them.”

Kate Fox's visit to the Moodie cottage the following September provided Susanna's first opportunity to see the young woman's powers with her own eyes. After a few minutes of small talk in the dining room, Miss Fox asked if Susanna would like to hear some rappings. Susanna replied that she would: “Very much indeed, as it would confirm or do away with my doubts.” So Kate Fox closed her eyes and asked the spirits if they would communicate with Mrs. Moodie. Straightaway, there were three loud raps on the table. “In

spirit language,

” Susanna later wrote to Bentley, this meant yes. “I was fairly introduced to these mysterious visitors.”

Miss Fox told Susanna to write a list of friends, some of whom were dead and some alive. The medium turned her back on Susanna as the latter wrote, then told her hostess to run her pen slowly down the list. Every time Susanna's pen lingered on a dead friend, the spirits would rap five times; for a living friend, they would rap three times. “I inwardly smiled at this,” Susanna later wrote to Richard Bentley. “Yet strange to say, they never once missed.” Next, Susanna wrote, “Why did you not keep your promise?” under the name of Anna Laural Harral. Anna was the daughter of Thomas Harral, who had published Susanna's work in

La Belle Assemblée,

and she had been Susanna's best friend before her early death in 1830. In their twenties, the two young women had promised each other that the one who died first should appear, if possible, to the other. Susanna was startled when the spirits immediately rapped out, “I have often tried to make my presence known to you.” Susanna then asked the spirit to spell out its name. It was instantly done. “Perhaps no one but myself on the whole American continent knew that such a person had ever existed,” she wrote.

Susanna was shaken by these revelations, but her guard was still up. So Miss Fox put the spirits to work in different ways. First, Susanna felt a table vibrate under her hands as if it had a life of its own. Then, at Kate Fox's suggestion, she stood by a door in such a way that she could see

both its sides, and felt similar vibrations in the door. Miss Fox took Susanna out to the garden, where a few Michaelmas daisies still glowed mauve in the late afternoon light. Susanna felt strange vibrations under her feet, in the stone path and in the earth. “Are you still unbelieving?” the medium inquired. Susanna was torn between her eagerness to believe and intelligent scepticism. “I think these knocks are made by your spirit and not by the dead,” she finally told her visitor. Kate Fox was determined to convince this well-known Canadian writer, who could be such a useful supporter. “You attribute more power to me than I possess,” she insisted. “Would you believe if you heard that piano, closed as it is, play a tune?” The piano was not played by invisible fingers that afternoon. But Susanna convinced Kate Fox to postpone her trip and come back for the evening two days later, when John would be present.

To a casual observer, it appeared to be a charming scene of mid-Victorian domesticity: the oil lamp on top of the upright piano glowed, and Kate Fox's long dark hair glinted in its light, while Susanna's eyes sparkled with interest. Jane, the maid, stood demurely by the door, in case she was needed. John Moodie picked up his flute, and suddenly, while Susanna and Kate were standing by the piano's closed lid, they heard its strings play the accompanying melody. “Now it is certain that she could not have got within the case of the piano,” Susanna mused.

When John stopped playing, the piano notes softly died away. John and Susanna looked at each other with wonder. Jane was open-mouthed. John turned to the slim young woman between them and asked the spirits to tell him what was engraved on the inside of a mourning ring, enclosing a curl of his grandmother's hair, that he always wore. As Kate stood gracefully listening, they all heard the spirits' obedient raps. The number of raps correctly identified the dates of his grandmother's birth and death. John himself had to take the ring off to check the spirits' accuracy, since he had forgotten the dates himself. “I thought I would puzzle them,” Susanna later wrote to Bentley, “and asked for them to rap out my father's name, [and] the date of his birth and death.” She thought it was a trick question because there were so many eights in the

answer: Thomas Strickland had been born on December 8 and died on May 18, 1818. Without a pause the spirits rapped out the right name, dates and even the cause of death.