Sisters in the Wilderness (39 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

John's enemies smelled blood. Although the appointment of a deputy sheriff was legal, the “farming of offices” was against the law. Judge Allan Ramsey Dougall, an Orangeman and another old adversary of

John's, watched Ockerman's conduct with eagle-eyed attention. As soon as he had enough evidence to prove Ockerman was acting with far too much independence to be described as a mere “deputy,” Dougall pounced. In October 1859, four months after Thomas Traill's death, Dougall brought a formal court action against John for “the purpose of bringing before the Court of Queen's Bench the legality or otherwise of the proceedings of Mr. Sheriff Moodie in reference to his office.” John was summoned to appear before the assizes in Belleville in December to answer the charges.

Susanna was convinced that the charges against her beloved husband would be dismissed, but she was wrong. The presiding magistrate at the Belleville Assizes ruled against John. In the spring of 1860, the case went to the Court of Queen's Bench in Toronto, which ruled that Moodie was technically guilty of infringing the statute regarding the farming of offices. But the whole issue of John's future as sheriff was left in a dreadful limbo. On the one hand, the Reformers who dominated the United Provinces government were reluctant to terminate John's appointment as sheriff. He had been a loyal, hard-working, honest sheriff, and Belleville's Orangemen were notorious for their vicious partisanship. On the other hand, the government was not prepared to come to his aid: they didn't want to offend Belleville's cabal of Tory lawyers. So the case was left hanging in a crossfire of appeals and petitions.

Susanna was stunned by this turn of events. She insisted to Catharine that John had the “sympathy of the whole county” against the “malignity of the men who have done thisâ¦.So do not grieve for me, my sister, my dear tried friend.” She also realized that the case could drag on for months: “I wish it were overâ¦. Uncertainty is always worse to bear than the pressures of sorrows known. When we know what we have to expect, the mind rises to meet the emergencies of the case, and we can mature plans for the future.” The behaviour of their Belleville neighbours both enraged and scared her. Anger made her insist that she and John would turn their backs on Belleville as fast as possible if they lost the case: “I have no ties to bind me to Belleville, beyond the dear home

that has sheltered us for so many years, and the trees I have with my own hands planted, and last, not least the graves of my dear boys.” But this anger was a defence mechanism against a much more deep-seated emotion: fear. Susanna was worried about John: “The blow fell very severely, and I never saw him look so pale and worn.” Susanna had just watched her strong, stalwart sister Catharine accommodate herself to widowhood, and she was terrified of facing the same prospect. By now, she knew that Catharine had an emotional stamina that she lacked.

John Moodie was not the only person to fall victim to the obstinate determination of members of the Orange Order in British North America. At the Order's annual parade on July 12, there were always Orange-Green brawls between Protestants and Catholics on Belleville's Front Street. “It appears a useless aggravation of an old national grievance to perpetuate the memory of the battle of the Boyne,” Susanna had written indignantly in

Life in the Clearings.

Orangemen had also been central in the election rioting in Toronto in 1841 that left one man dead. Small wonder that Susanna insisted that the activities of the Orange Order “pollute with their moral leprosy the free institutions of the country.” But in 1860, a few weeks after the Court of Queen's Bench in Toronto ruled against the sheriff of Hastings County, the Orangemen outdid themselves in a display of muscle. This time, the victim was none other than Edward, Prince of Wales, the nineteen-year-old heir to the British throne.

Prince Edward, eldest son of Queen Victoria, had arrived in the colony for the first ever royal overseas tour. One of his first public appearances was in Montreal, where he was to lay the last stone of one of the most splendid structures in the British Empire: the Victoria Bridge, which spanned the two-mile width of the St. Lawrence River and was named in honour of his mother. The bridge, designed by the great British engineer George Stephenson with an innovative construction of tubular girders, had taken almost five and a half years to complete and was the longest bridge in the world. On August 25, the slim young prince clambered onto a train pulled by a huge Grand Trunk Railway locomotive and was taken to the centre of the bridge to hammer into place the final rivet. He and his entourage then clambered back into the train and returned to the immense locomotive shed at Pointe St. Charles, where the City of Montreal had laid on a luncheon for one thousand guests. “âGod save the Queen' was played as His Royal Highness entered, and when he was seated the whole company sat down and fell to,” reported

The Daily Globe

. With the opening of this engineering masterpiece, the Prince of Wales had inaugurated Canada's magnificent Railroad Era.

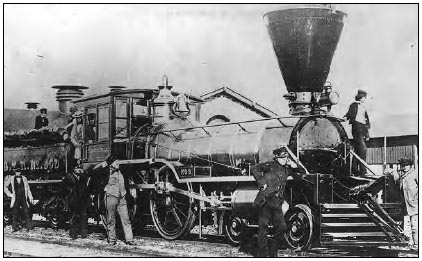

One of the first steam engines (with a cow-catcher at the front) of the Grand Trunk Railway. Canada's Railroad Era had arrived.

The Victoria Bridge was more than just an engineering triumph. Its glorious opening ceremonies allowed the young, sprawling colony, with its rapidly swelling population and fractious politics, to show itself off to its future sovereign. For the first time in most of their careers, cabinet ministers donned the British civil uniform designed for colonial officials. It was a flattering costume that included a sword and navy jacket with lashings of gold braid and facings. The

Globe

carped that John A. Macdonald, joint premier (along with George-Etienne Cartier) of the United Provinces, had no idea how to walk with a sword sheathed at his side, and with his “devil-may-care air, managed to get his cocked hat stuck on one side ⦠in a most ridiculous fashion.” But none of those present at Montreal could be oblivious to a shared pride in the dignity and autonomy of their own government.

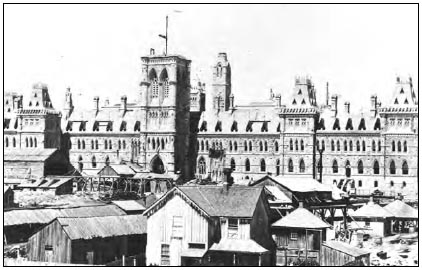

Ottawa's splendid Gothic Parliament Buildings in the 1860s, during construction.

From Montreal the Prince of Wales proceeded to Ottawa, to lay the cornerstone of the new Parliament Buildings. Susanna was one of the few people in British North America to laud Queen Victoria's choice of the swampy lumber town as the new capital, instead of either Toronto or Montreal. “A very few years will make Ottawa worthy of the royal favour. In natural beauty it far surpasses all its more wealthy rivalsâ¦. The Queen showed much taste in picking it.” The young Prince must have been overwhelmed by his welcome, and by the peculiar Canadian tradition of building triumphal arches of leafy boughs along the official route. “Here is the universal programme,” declared one newspaper reporter. “Spruce arches, cannon, procession, levee, lunch, ball, departure; cheers, crowds, men, women, enthusiasm, militia, Sunday school children, illuminations, fire works, etcetera, etcetera,

ad infinitum.

”

It soon became evident, however, that the wild enthusiasm for the Prince was getting out of hand. John A., in particular, was perturbed by

a nasty undercurrent in the outpouring of loyalty to the British Crown, thanks to the machinations of the Orangemen. In the United Kingdom, the parades and banners of the Orange Order were illegal, so the Prince of Wales's advisers had told Canadian authorities that the Order could make no public demonstrations during the royal visit, because Edward could not acknowledge an illegal organization. Most Canadian Orangemen reluctantly accepted the veto. However, the fiercest among them bristled at this insult to their independence. Since Orange Order parades were perfectly legal in Canada, why should Canadians follow English rules? The Orangemen in Kingston, John A. Macdonald's own riding, built a particularly glorious arch of evergreens, put on their orange-and-blue uniforms, tuned up their fife-and-drum band and clamoured to be allowed to join the parade when the Prince disembarked at Kingston's docks.

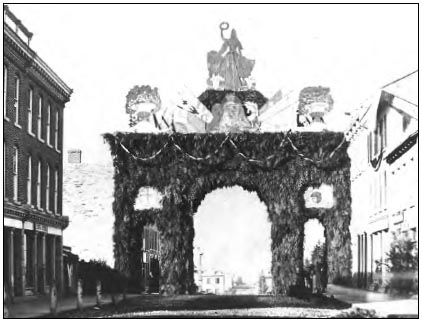

Wherever the Prince went, he passed under massive temporary arches of spruce branches: this one welcomed him to Sparks Street, Ottawa.

The result was a stand-off. The Prince refused to disembark from the steamer on which he was travelling down the St. Lawrence River; the Orangemen refused to back down. So the royal steamer weighed anchor and set off towards the Bay of Quinte and the next stop on the royal itinerary: Belleville. But the infuriated Kingston Orangemen got there first, by train. They persuaded their zealous colleagues in Belleville to insist that the loyal Order of Orangemen be allowed to make their demonstration there.

As sheriff of Victoria County, John Dunbar Moodie was part of Belleville's welcoming committee, and Susanna, now one of the best-known writers in the colony, was at his side amongst the other civic dignitaries. Early that bright September morning, the Moodies had walked from their house down to the wharf, admiring as they went all the decorations in the centre of town. Belleville had gone overboard with preparations: the streets were lined with sheaves of wheat, cornstalks, bunting, Chinese lanterns and glowing bunches of orange day-lilies. Ten triumphal arches were positioned along the Prince's scheduled route. Farmers from the surrounding countryside had loaded their wives and families onto their wagons and converged on the town to see the show. A bevy of fifty young ladies on horseback were scheduled to meet the Prince when he set foot on firm ground.

But once again, the Prince of Wales never stepped ashore. In the face of yet more Orange intransigence, the steamer bearing the royal party simply chuffed away. It wasn't until Edward reached Cobourg that he and his retinue were finally able to enjoy one of the balls organized in his honourâand that was largely because the train in which Kingston's Orange troublemakers were pursuing him had broken down ten miles from the town. Back in Belleville, the townspeople “chaffed with suppressed rage,” according to

The Daily Globe

's correspondent: “Though the gilded crowns, many coloured flowers and flags give an air of gaiety to the place, yet such a quantity of sullen, discontented faces I have never before witnessed.”

The Moodies were outraged by the discourtesy to the royal party. But it would have been foolish for John to have tried to stop the Orange

Order's demonstrationâtoo many of the most prominent townsfolk, and all his political enemies, were involved. George Benjamin, publisher of the

Belleville Intelligencer (

whom Susanna had caricatured so viciously in her writings), was one of those who organized the pugnacious defence of Orange Order rights in Belleville. Benjamin's role came as no surprise to John and Susanna, since John's old adversary was still pursuing the sheriff with equal zeal: Benjamin told Premier John A. Macdonald that John Dunbar Moodie's dismissal from office was “the most important” of all the issues in his riding.

The uncertainty of the court case, the belligerence of the Orange-men, the hostility of George Benjaminâthe sheriff was under a lot of stress. In July 1861, John Moodie suffered a stroke that paralysed his left side. A hysterical Susanna quickly called in Dr. Lister, the well-known Belleville physician, and watched aghast as he applied the favourite all-purpose remedy of the nineteenth-century: cutting open a vein to bleed the patient.