Sisters in the Wilderness (42 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

Catharine's beloved Westove, at Lakefield: any Strickland relative was warmly welcomed.

Now in her sixties, Catharine beamed at the younger generation even as she cast a disapproving eye at their values. When she stayed with Agnes Fitzgibbon in Toronto in 1863, she clucked at the way that young women in the city behaved, declaring herself “rather disgusted with the way in which they dress for effect in public.” While Agnes and her Toronto friends revelled in the arrival of music halls, London fashions and racy novels, Catharine shared her disapproval with Frances Stewart: “The luxurious style of dress, amusements and idleness of the young men and women of the last few years have encouraged a greater laxity in their manners and ideas. You and I perfectly agree in our opinion, respecting the want of delicacy in the fast dances, besides the effect on the moral character.” Yet for all her busybody gregariousness and talk of the “good old days” (tales of which must have horrified her nieces and nephews), Catharine had a kind heart and was a welcome guest in many households. Her white hair neatly tucked under a starched cap, her black gown (a castoff from Agnes) frayed at the cuffs and her bright blue eyes sparkling with life, she quickly determined what needed to be done. She would sit up all night with a feverish child, teach a musical grandchild to pick out a melody on the piano, talk about old times with the dying, or help lay out a corpse. Small wonder that her shy, stay-at-home daughter Kate regularly received notes that Catharine's return from some sociable little trip would be delayed because her hosts “all want to keep me longer with them.”

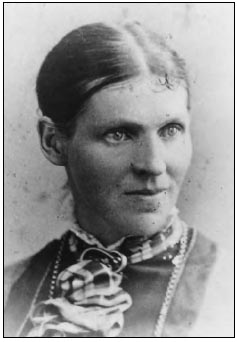

Kate Traill, Catharine's eldest daughter, who devoted her life to her mother's welfare.

However, Catharine was far from a merry widowâshe still needed to earn money. The first entry in her journal for 1863 begins: “On examining the state of my purse I find just $4.30. This is all the funds I have to begin the year with. It is true that I have half a barrel of flour, and some meat and I have often been without meat and money. God will provide as heretofore.”

Catharine had known from childhood that God only helps those who help themselves; and for her that meant writing. Over the past thirty-five years she had worked in a variety of genresâchildren's stories, romances, sketches of nature and autobiographical narratives. Although none of her books had made her a fortune, they sold well and had established her reputation in both Britain and Canada. She continued to churn out stories for educational and children's magazines, and she knew which subjects were the perennial favourites of European readers, then and now â“Snow, ice storms, forest scenery ⦠a flight of snowbirds would make a pretty little poem.” But her submissions were returned with demoralizing frequency, and with advancing age, she had less tolerance for hustling unsympathetic publishers or pleasing periodical editors. Like Susanna, she felt out of touch with the tastes of the main audience for her publications: the British. Her attention was increasingly focussed on the world at her own doorstep, within British North Americaâin particular, the natural world.

Ever since she had crossed the Atlantic, Catharine had collected and studied flowers, grasses, mosses, lichens and ferns. Nature study was a relief “from the home-longings that always arise in the heart of the exile,

especially when the sweet opening days of Spring recall to the memory of the immigrant Canadian settler old familiar scenes â¦when all the gay embroidery of English meads and hedgerows put on their bright array.” Nature, for Catharine, was pervaded with divine purposeâits beauty and harmony illustrated God's power and goodness. She never found a plant that she couldn't love both for its looks and as an example of God's creation. The bud of the water-lily, lying just below the surface, “is ready to emerge from its watery prison and in all its virgin beauty expand its snowy bosom to the sun and genial air,” she observed in a letter home in her first months in Upper Canada. Every year, she watched the changing seasons with a delight that always crept into whatever book she was writing at the time. “The pines were now putting on their rich, mossy, green spring dresses,” reads a passage in her

Canadian Crusoes

. “The skies were deep blue; nature, weary of her long state of inaction, seemed waking into life and light.” In

The Female Emigrant's Guide,

she provided a month-by-month description of natural events, which covers everything from croaking frogs to wildflowers. In August, “the squirrels are busy from morning till night, gleaning the ripe grain ⦠they seem to me the happiest of all God's creatures, and the prettiest.”

But Catharine's nature study wasn't all Wordsworthian reverie and nostalgia for Suffolk's daisies, bluebells and buttercups. She took a serious interest in every aspect of a plant: its appearance, its life cycle, its medicinal and food value, its relation to other plants. During her first decade in the silent and unexplored backwoods, she searched for the name of any unfamiliar species in the only botanical text she could lay her hands on: Frederick Pursh's

Flora Americae septentrionalis

(

North American Flora

), published in 1814, which Frances Stewart had lent her. Since Catharine had never studied Latin, she stumbled through Pursh's descriptions, “and when I came to a standstill I had recourse to my husband.” She copied Pursh's use of the Linnean classification system of plant species, largely based on the number of stamens and pistils in the flower. Her husband's books were lumpy with all the pressed specimens she had inserted between their pages. Her journal was full of careful notes.

Had Catharine been born a hundred years later, she would have become a serious scientist. But stuck in remote Douro Township, or on the Rice Lake Plains, Catharine had as much hope of mingling with professors of botany, who could tell her exactly how to mount and label her specimens, as she had of mingling with important authors in the London publishing business. She was so poor that she was never able to afford to visit the greatest natural wonder of her adopted land, Niagara Falls. She couldn't even do accurate plant drawings; unlike Susanna, she had never mastered the art of flower-painting. She was an avid collector, and her “herbarium,” or collection of dried specimens, was one of her greatest sources of pleasure. Album after album was filled with elaborate arrangements of dried material.

Today, Catharine's scrapbooks are lodged safely in the archives of the Museum of Nature in Ottawa. Their decaying pages, with their fragile red lichens still adhering to the rag paper and the blossoms of fireweed still purple 130 years after they were picked, give us a warm insight into their creator's mind. The books bulge with lovingly handled plants, many of which she was the first to identify in the countryside around Lakefield. Specimens are arranged artistically on the page. One album begins with an inscription encircled by a wreath of pressed sphagnum moss and pearly-white everlastings. Another features sprays of pressed ferns, anchored on white birch bark and decorated with faded maple leaves. But vital scientific informationâa plant's Latin name, or the habitat and date on which it was foundâis often missing. Catharine was as likely to accompany her specimens with biblical quotations (especially from the Psalms or Revelations) as with proper notation. Her albums include tiger moths, their delicate wings flaking with age, and the orange feathers of a northern oriole.

In the mid-nineteenth century, there was a market for Catharine's type of collection and display. Friends bought her artistic arrangements of pressed flowers, just as they bought Susanna's flower paintings, as aesthetic pleasures and keepsakes of their creator. Catherine sent the dried seeds of unusual plants to a professor of botany (probably Robert

Graham, who held the chair from 1819 to 1845) at Edinburgh University. Provincial flower shows had special sections devoted to amateur herbariums: Catharine's collection of dried native plants won a prize at the Kingston Provincial Fair in 1856, and in 1862 another collection was awarded second prize at the Provincial Exhibition in Toronto. Catharine knew her albums were well put together, and when her fern collection did not win a prize at the same show, she took umbrage: “They were without doubt the best things there of the kind ⦠it has now become so partial a thing the awarding of the prizes that I shall make no further attempts to send any collection to the Provincial Shew.” When fire swept through Oaklands in 1857, instead of grabbing old letters, clothes or keepsakes, Catharine rescued from the crackling flames a half-finished manuscript on plants. Once she was settled at Westove, she decided to focus on her botanical interests as her next publishing project.

With some difficulty, Catharine managed to update her limited collection of botanical texts to include Maria Morris's

Wildflowers of Nova Scotia

(published in 1840). She also got hold of a copy of the 1833 classic

Flora Boreali Americana,

by the illustrious Sir William Jackson Hooker, since 1840 director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. Like Pursh's, however, Hooker's tome was written for professional scientists, not enthusiastic amateurs like Catharine. Catharine's preferred model for botanical writing was

The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne

by the eighteenth-century naturalist Gilbert White, which had first appeared in 1789 and which she had read as a child. White, a country parson who lived in Hampshire, kept a careful record of the seasonal changes in his beloved birthplace. His work reflects a poetic affection for wild life and nature, and a love of the picturesque in landscape. Catharine decided to devote herself to writing a usable botany manual for Canada, written in the literary style of Gilbert White.

The potential value of British North America's plant life had been recognized as early as 1730, when company surgeons of the Hudson's Bay Company began to include botanical descriptions and specimens of native plants in the regular reports that they sent back to London.

During the eighteenth century, most specimens collected by explorer-naturalists were shipped straight to Kew Gardens in London. However, by the time the Strickland sisters arrived in British North America, a handful of the colony's more affluent residents were showing some curiosity about the flora and fauna that surrounded them. Natural history societies had been established in Quebec, Montreal and Halifax during the 1820s. Toronto finally got its own Horticultural Society in 1834, and a botanical garden near Government House soon afterwards. The learned lectures and field expeditions offered by these societies were even considered suitable “scientific” activities for highbrow womenâanimal biology involved blood; mineralogy involved dirt; while horticulture involved only plants and flowers. The stylish Lady Dalhousie, wife of the Governor-in-Chief of British North America from 1820 to 1828, regularly swathed her head in muslin, to keep off the bugs, and set off with specimen box, magnifying glass and a retinue of attendants into the farmlands around Quebec City. Once her specimens were dried, university-educated members of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec (an organization founded by her husband) showed “M'lady” how to label them properly. Lady Dalhousie, whose articles appeared in the Society's

Transactions,

was one of the few women of her time to be published alongside male botanists.

Catharine lacked the instruction that Lady Dalhousie enjoyed, but she had far more opportunity to concentrate on her botanical interests. From her earliest years in the bush, she would try to cultivate the plants she had found growing in the wild, or had seen Indian women using for their healing properties. She sold more than a dozen natural history articles to the

Anglo-American Magazine,

published in Toronto, and the Rochester-based

Horticulturist.

She was as maternal with plants as she was with her own children. She oohed and aahed over every discovery with protective pride, and in her published articles she used familiar and maternal metaphors alongside scientific terminology. When she could not discover an existing name for flowers and plants in the “wild woods,” she wrote soon after her arrival, “I consider myself free to become their floral godmother and give

them names of my own choosing.” The longer she remained in the colony, however, the more she wondered whether progress towards permanent settlement was such a marvellous advance. So much was being lost as forest was cleared, roads constructed and towns founded.

Much of her concern for the wilderness was expressed in the

dum-dedum

of sentimental doggerel:

O wail for the forest, the proud stately forest,

No more its dark depths shall the hunter explore,

For the bright golden main

Shall wave free o'er the plain,

O wail for the forest, its glories are o'er.

But she also tried to alert others to the slow erosion of native Canadian species. In 1852, she protested to the editor of the

Genesee Farmer

that in the rush to clear land, stock greenhouses and cultivate annuals for gardens, indigenous forest plants were disappearing. “Man has altered the face of the soil,” she wrote with despair. “The mighty giants of the forest are gone, and the lowly shrub, the lovely flower, the ferns and mosses that flourished beneath their shade, have departed with themâ¦. Where now are the lilies of the woods, the lovely and fragrant Pyrolas, the Blood-root, the delicate sweet scented Michella repens? Not on the newly cleared ground, where the forest once stood.”