Sisters in the Wilderness (51 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

Catharine finally had more financial security than she had known for years. “Dear valued friend,” replied Catharine, in a script as firm as it had been twenty years earlier, “You can hardly think how welcome [your letter] provedâ¦.How can I thank all the kindness of the generous givers of this large sum of money awarded to the aged authoress. It does seem too great for such small servicesâ¦. And in what words dearest Friend shall I thank you, and all my known and unknown friends in England and Ontario. I can only adopt the hearty simple phrase used by the Indian women of Hiawatha villageââI bless you in my heart.'”

The formal presentation came early in 1899. The tribute acknowledged Catharine's major literary works, and concluded: “We cannot

forget the courage with which you endured the privations and trials of the backwoods in the early settlement of Ontario, and we rejoice to know that your useful life has been prolonged in health and vigour until you are now the oldest living author in Her Majesty's dominion. Nearing the close of the century we desire to pay tribute to your personal worth, and we ask your acceptance of this testimonial as a slight token of the esteem and regard in which you are universally held.”

A few months later, Kate Traill took her ninety-seven-year-old mother to Minnewawa, her cottage on Stony Lake. Catharine sat on the shady verandah, scattering crumbs for her beloved birds and watching canoes skim across the azure water. She loved “the wild and picturesque rocks, trees, hill and valley, wild-flowers, ferns, shrubs and moss and the pure, sweet scent of pines over all, breathing health and strength. If I were a doctor,” she had once written, “I would send my patients to live in a shanty under the pines.” In the summer of 1899, she would occasionally ignore Kate's protests and, cherrywood staff in hand, totter off to the woods behind the cottage to look for berries and flowers. Very occasionally, she would pick up a pen to write to distant relatives.

Kate Traill's island of Minnewawa, on Stony Lake, where Catharine loved to smell the pines and scatter crumbs for warblers and orioles.

As the August nights lengthened, and the evening breezes grew cooler, Kate helped her mother board the steamer for the return journey to Lakefield. Soon after Catharine was settled back in her beloved Westove, she began a letter to a cousin in England about a London publisher's decision not to publish one of her children's stories. “I had many misgivings as to the merits of the composition,” wrote Catharine, with typical self-deprecation. “I never see anything good in my writings till they are in print and even then I wonder how that event came to pass.”

Catharine's head began to nod before she had finished the letter. Kate gently took the pen out of her hand and, as her mother jerked into wakefulness again, Kate suggested to Catharine that she could finish the letter later. The old lady gave her faithful daughter a grateful, sweet smile, and settled back into her chair as the evening shadows began to lengthen.

Catharine's final hours were far more peaceful than those of her sister, Susanna. With the blessed calm she had radiated throughout her life, she died quietly in her sleep two days later, on August 29, 1899.

Postscript

T

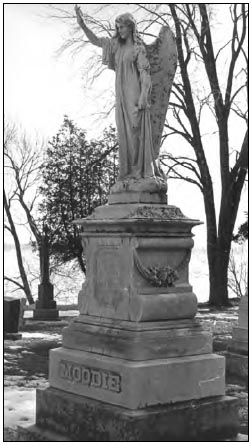

he best memorial to the lives of Catharine Parr Trail and Susanna Moodie is the angel above the Moodie grave in Belleville cemetery. A stalwart figure in her carved robe and mossy wings, she towers over her neighbours and holds her arm aloft in defiance of the winds from the Bay of Quinte. In her hand she clutches a starâsymbol, perhaps, of the immigrant's hope that a better future lies ahead, and that he or she can control it. It is unlikely that the two Strickland sisters who came to Canada ever felt in control of their destiny. Yet as each neared the end of her own long life, with beloved children close by, she would have acknowledged that the journey had been worthwhile. Each had arrived in the New World a writer, and had continued writing despite hardship. Each had seen most of her children happily settled. Both had watched the rough-and-ready colony of 1832 embark on its transformation into a

remarkably vigorous, prosperous nation. And through their books, both women had themselves helped to shape the culture of their adopted countryâCatharine through her descriptions of landscape and natural history; Susanna through her portrayals of pioneer experiences and colonial society.

Yet today, one hundred years after Catharine's death, she and Susanna would find modern Canada unrecognizable. Only two of their various dwellings survive: the Moodies' pleasant stone cottage on Belleville's Bridge Street and Catharine's beloved Westove in Lakefield. These homes are now jostled by brick and clapboard neighbours of much more recent date, with car ports, swing sets and gas barbecues in their yards. The rest of the log cabins and cramped cottages in which the sisters scraped and scribbled in Ontario are long gone. We have moved far beyond sagas of wilderness survival and tales of rural life.

Hamilton Township, where the Moodies spent their miserable early months, is now dotted with gentrified farmhouses to which Torontonians drive, along a six-lane highway, for country weekends. Trailer parks and campgrounds crowd onto the south shore of Rice Lake, which Catharine described so

lovingly in

Canadian Crusoes

. You can find historical plaques here and there, commemorating Susanna's log cabin on Lake Katchewanooka, or the sites of Wolf Tower and Oaklands, the Traill homes on the Rice Lake Plains. But on the plaque that is planted firmly in the middle of Lakefield to mark Susanna's connections with the village, Catharine's name is misspelled. The most handsome mansion in Lakefield remains The Homestead: a yellow brick reminder that the only Strickland who was a successful pioneer was Sam.

The marble angel that marks the Moodie grave in Belleville cemetery.

Yet the legacy of Susanna and Catharine is as sturdy as Sam's mansion or the Moodie angel in the Belleville cemetery. Their most important books are still in print. More than a century has passed since the sisters' deaths, but plenty of contemporary Canadians have shared the feelings they captured on paper about emigration, and their ambivalent relationship with a landscape both majestic and savage. Every new Canadian who thinks longingly of “home” and every brave adventurer who sets off into the bush, brushing off black-flies and marvelling at nature, is following in the sisters' footsteps.

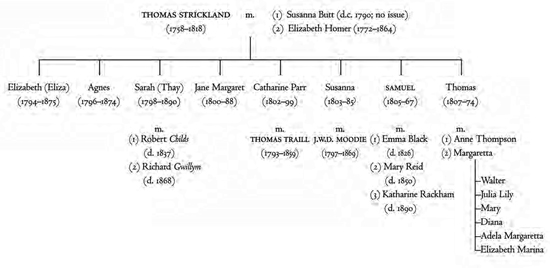

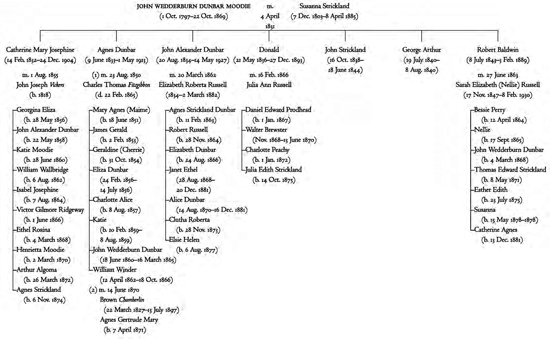

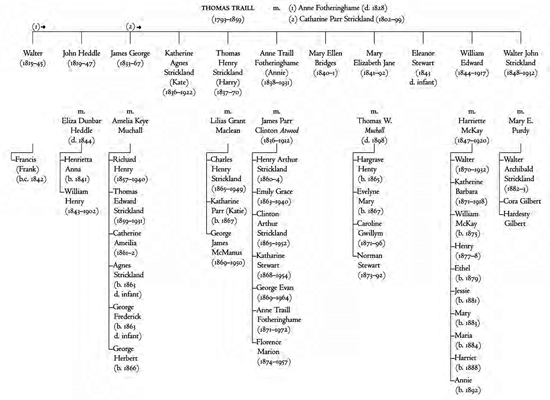

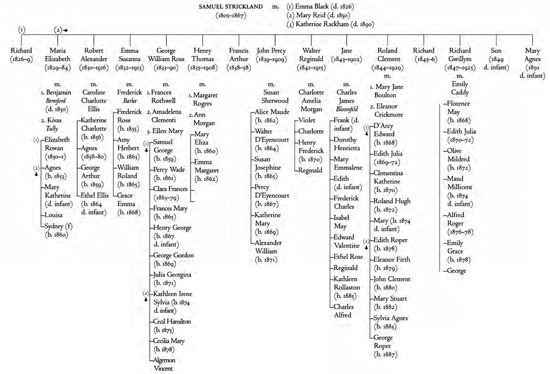

Family Trees

Acknowledgments

I

would not have had the material, the time or the nerve to write this book had it not been for Professor Michael Peterman of Trent University. Thanks to Michael and his two colleagues, Professor Carl Ballstadt of McMaster University and Professor Elizabeth Hopkins of York University, I was able to draw on three volumes of Traill and Moodie correspondence as sources. The three academic authors collected, edited and published all the extant letters by John and Susanna Moodie, and 136 of the approximately 500 letters written by Catharine Parr Traill. The three volumes saved me from months of labour in the National Archives of Canada, squinting over copperplate handwriting and cross-written letters. In addition, throughout the gestation and birth of this book, Michael has provided information, access to his research, suggestions for further reading and feedback. He showed me around Lakefield and Peterborough, and he and his wife Cara

welcomed me to their home. After our first meeting, Michael said, “Well, I think the ladies will be safe with you.” I hope I have justified his confidence.

Both Beth Hopkins and Carl Ballstadt were also generous with their support. The insights into the sisters that I gained from Beth, as she drove me across southern Ontario one fall evening, gave valuable shape to my own impressions. I have drawn extensively on journal articles by all three authors.

I am also indebted to two rigorous and enthusiastic readers. My good friend Sandra Gwyn rescued a first draft of the book with imaginative and clear-headed suggestions. Dr. Sandy Campbell, who teaches in the English Department of the University of Ottawa, helped place the two sisters in their literary context and drew my attention to Susanna's slave narratives. In addition, she eagerly joined me in my exploration of the sisters' complicated personalities and relationship, as well as their importance as nineteenth-century authors.