Sisters in the Wilderness (24 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

Susanna considered St. Thomas's Anglican Church “an eye-sore.”

As sheriff of Victoria County, John was in a sensitive position. His job was to keep the peace among the various factions. This meant, in his view, staying aloof from the ethnic, sectarian and political schisms within the populace. He might have managed to stay away from ethnic and sectarian squabbles, but there was no hope of avoiding the political

quarrels. A chasm separated the Tories, who swore undying loyalty to the British crown, and the Reformers, who felt that the colony should be given a greater degree of control over its own affairs. John tried to stay on the fence, by attending both the Anglican and the Presbyterian churches, and by appointing as his deputy sheriffs one Tory and one Reformer. But “however moderate your views might be,” Susanna discovered, “to belong to the one was to incur the dislike and ill-will of the other.”

While John had to deal with Belleville's frock-coated lawyers and merchants, who pursued their public vendettas through elections, legal cases and business practices, Susanna had to deal with their wives. Many were the kind of educated women for whose company she had hungered in the wilderness. But now she discovered that Belleville wives “entered deeply into this party hostility; and those who ⦠might have become friends and agreeable companions, kept aloof, rarely taking notice of each other when accidentally thrown together.” Her hands still roughened by field work, she also found them snobbish and superficial: she deplored their love of finery and their sneering disregard for farmers and “mechanics.” In fact, she found herself in the unfamiliar position of scorning their hoity-toity pretensions, which were remarkably similar to those with which she had arrived in Canada.

A chilly social reception was only the start of the Moodies' problems. The knives were out for the new sheriff before he'd even set foot in the courthouse. There were a lot of civic offices attached to the new Victoria District, but the permanent, full-time office of sheriff was the plum. Although the sheriff 's job had no salary attached, its holder could expect an income of at least $200 a year from fees received for serving writs and subpoenas. This was a very modest income for a professional man: John had earned 325 pounds a year as paymaster to the militia, and a successful lawyer in Upper Canada might bring in $1,000 a year. However, the real money for John came from the sheriff 's right to keep any proceeds from the sale of impounded property and any court-imposed fines he collected. Income from these sources could amount to five or six times the

total of fees received. The prospect of an annual income of more than $1000 meant that various Belleville worthies had been competing for the office long before the district was formally established. The strongest candidate was Thomas Parker, a Tory bully who was the former deputy sheriff of the Midland District (which then included what would later become the Victoria District) and the Belleville agent of the Commercial Bank in Toronto.

Parker was desperate to be sheriff because he was close to bankruptcy. He thought he had the job in the bag. When he heard that some

arriviste

half-pay Scot, who knew little about Belleville and nothing about municipal politics, had upstaged him, he was mad as hell. And so were all his friends. Anglican Tories to a man, they decided that the newcomer must be a Reformer and a Presbyterian, and that it was their civic duty to prove he was an incompetent sheriff. Knowing that the Moodies were chronically hard up, Parker played a vicious cat-and-mouse game with John. He and his Tory pals delayed payments to the sheriff on trumped-up grounds and brought nuisance lawsuits against him, which never came to anything but cost John money. John was soon begging the Toronto authorities for an additional appointment: “At present I am hardly able to support my family with the most rigid economy.”

On top of all this unpleasantness, John had a messy start to the new job. Because he would be handling public funds, he had to produce two letters from people who would act as guarantors for him. But they had to be men known to the Toronto authoritiesâwhich was a challenge for John, who had rarely met any of the colony's prominent lawyers, merchants and landowners while he was stuck in the backwoods. He first nominated his two brothers-in-law, Thomas Traill and Sam Strickland, but after several weeks he heard that they didn't meet the exacting standards of the Toronto bureaucrats. As time ticked on, he grew anxious that his appointment wouldn't be confirmed before the first Quarter Sessions were due to be held in Belleville's new courthouse. He produced a second pair of guarantors, and then a third. The second pair of guarantors was finally accepted, and, at the last moment, John was sworn in

and documented as sheriff. But his cheery self-confidence was punctured. He was sure that Thomas Parker was already denigrating him to the government. In a letter to Sir George Arthur in February 1840, ostensibly thanking the Governor for the job, John rushed to defend himself from any base accusations that might have reached Toronto ears. The Governor assured him that “Mr. Parker has not made any communication of the kind, directly or indirectly.”

Initially, Susanna kept her distance from the tiresome infighting of Belleville citizens and concentrated on her children and her writing. Now that she was out of the woods, she wanted to reestablish herself as a professional writer so that she could supplement the family income. She had more time: she no longer had to care for livestock (though, like most town-dwellers, she still kept chickens and had a vegetable garden), and much of the arduous work of childcare, cleaning, laundry, cooking and baking had been delegated to the series of young Irish maids who had taken Jenny's place. And Susanna finally had in the New World an editor who valued her workâJohn Lovell, the most famous printer-publisher in nineteenth-century Canada, who had first approached her two years earlier to contribute to his

Literary Garland.

Lovell's support was just the encouragement she needed. He paid according to the quantity of pages (five pounds per sheet) rather than offering a set fee for each contribution, and he printed anything she sent him. The poems, serialized novels and short stories that Susanna produced were written for an English (or at least a British-educated) audience. She assumed that her readersâfor the most part, the merchant élites of Montreal and Torontoâwould prefer European settings and fastidious heroes. She also sent works that she had written twenty years earlier, in Suffolk. And she began to play with the idea of shaping some of her experiences of the past eight yearsâher first impressions of Canada, the early months in Hamilton Township, the ups and downs of life in Douroâinto sketches for publication.

Alongside her literary compositions, Susanna wrote personal letters to Lovell with all her family news (“I have been busy preparing my boys'

winter clothing”). Once or twice she and John even managed a trip to Montreal to see her editor and visit with his wife, Sara, and their family in their elegant townhouse on St. Catharine Street. “She was a pleasant companion,” Sara would recall. She admired Susanna's skill with water colours, and was amazed to hear that this English lady often had little Johnnie on her knee as she composed articles. Nostalgia for London tugged at Susanna as she glimpsed the cultured life of Montreal in the 1840s, with its concerts, theatres and soirées.

Susanna entrusted Lovell with the realization of one of her greatest dreamsâthe purchase of an inexpensive piano. In the backwoods, a piano had become the symbol of the lost state of gentility. Nothing had underlined their cultural and spiritual poverty so much as her inability to accompany herself on the piano when she taught her children the nursery rhymes and hymns of her youth. When Lovell secured one in Montreal and had it crated and shipped up the St. Lawrence to Belleville, Susanna was overjoyed. It almost made up for the ostentatious disregard that her Belleville neighbours continued to show for her literary achievements. At one point, one of her sons arrived home from school looking downcast; he said that another boy had jeered at him that “Mrs. Moodie invents lies, and gets paid for them.”

In spite of their fresh start, sadness and misfortune continued to dog the Moodies. In July 1840, Susanna gave birth to a sickly little boy. Christened George Arthur, after their benefactor the Governor, he clung to life for only three weeks. It was an ill omen. Next, in December, the Moodies' rented cottage caught fire, and they lost their furniture, clothing and winter stores. They almost lost two-year-old Johnnie, too: he had hidden in the kitchen of the burning building and was rescued only seconds before the roof collapsed. The fire traumatized Susanna, who had suffered one house fire already in the Moodies' backwoods log cabin, and who was still mourning the death of her infant four months earlier: “The agony I endured for about half an hour [before Johnnie was found] I shall never forget.” Had the calamity occurred in Douro Township, she would have rushed to her sister Catharine for solace.

Instead, she poured out her terrors in a letter to her mother and sisters in England. Astringent Agnes replied, “We were all much grieved to hear of your sad loss by fire and the distress it must have been to you and your lovely little flock, but if it had occurred before Moodie got the appointment it would have been of far more serious consequence.”

By 1842, the Moodies had settled into a pleasant house on the corner of Bridge and Sinclair streets, on the western edge of Belleville. Built seven years earlier of local limestone, with a verandah across the front and a spacious and separate kitchen wing to the rear, it boasted the kind of features that have come to be known as “wilderness Georgian”âa graceful staircase curling upwards with a narrow banister, and a front door with sidelights and a deep cornice supported by four gently tapered pilasters. It was light-years away from the squalid log cabin in the backwoods, and it brought back happy memories to Susanna of the little clifftop Regency cottage in Southwold that she and John had lived in during their first year of marriage. It was the wrong side of townâthe

haute bourgeoisie

of Belleville lived on the east side of the Moira, preferably on Church Street or John Street, at the top of the hill. But Susanna didn't care too much for gradations of status among small-town merchants She still regarded her refined English origins as all the rank she needed.

In later years, Susanna would look back on these years as being the most prosperous she and John ever enjoyed. They had (as she wrote to a friend in England) “many of the luxuries of life or such as are considered so in the Provinces,” and the house was “a grand and comfortable home.” She had at least two servantsâa maid and a handymanâwhich allowed her to establish a household routine that included as much reading and writing as possible. She rose at six o'clock, hurriedly read some prayers with her children, organized breakfast, made whatever bread and pies were required for the day, then sat down to write. She wrote steadily until dinnertime, turning a deaf ear to interruptions from the maid or children. After an early evening meal, she took a walk, then made or mended clothes until the light was too dim for her to sew any longer.

Once the lamps were lit, she returned to whatever manuscript she was working on.

The worst tragedy of her life struck the family a couple of years after they had moved into the Bridge Street house. One night in June 1844, Susanna awoke to find her pillow drenched in tears. In her dream she had taken Johnnie, then five, to England, to visit her mother at Reydon Hall. Her older sister Jane had appeared and told Susanna that their mother had died years earlier, but that Susanna had never been told because her English relatives felt she already had so many sorrows of her own. Susanna was badly shaken by the dream and spent the following day wracked with homesickness and a strange sorrow.

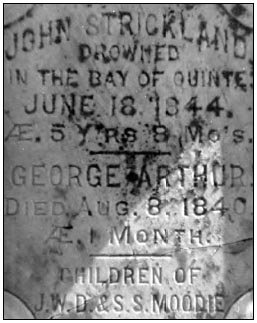

A memorial tablet for Susanna's

two lost sons: “hope has faded

from my heart.”

She was so preoccupied that she scarcely noticed that little Johnnie, who had been watching his two elder brothers fishing in the Moira, was late home. Suddenly an older child rushed into the kitchen, shouting that Johnnie was missing. John Moodie rushed along Bridge Street to the river and pounded up and down the bank, calling his son's name into the deepening twilight. The child had been washing all the brook trout that

his brothers had caught and had lost his balance as he leaned over the wooden wharf. Dunbar and Donald had been busy rewinding their lines and hadn't seen him leave them. Nobody had heard Johnnie's cries above the roar of the river. His father finally found the limp little body caught in the wooden supports of the wharf.

Susanna was devastated. The loss of her “lovely, laughing, rosy, dimpled child” was the “saddest and darkest [hour] in my sad eventful life.” Johnnie's death plunged her into a despair deeper than she had ever known; she never entirely recovered her mirth and spontaneity. She brooded inconsolably for months and wrote heartfelt poetry about her loss.