Sisters in the Wilderness (49 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

The best news came when, largely thanks to James Fletcher, the Ottawa publisher A.S. Woodburn agreed to publish her manuscript under the title of

Studies of Plant Life in Canada.

It would be a more modest production than

Wild Flowers of Canada

: Woodburn wanted to bring it out as a quarto-sized volume, with twenty chromo-lithographs from

drawings by Agnes Chamberlin. The introduction was quintessential Catharine, and encapsulated all the themes she had developed in half a century of botanical study. She wrote how, during her early years in the backwoods, forest flowers and shrubs “became like dear friends, soothing and cheering, by their sweet unconscious influence, hours of loneliness and hours of sorrow and suffering.” She insisted that her careful catalogue of plants, which included the Latin name for each plus a host of botanical and literary references, was “not a book for the learned.” The flowers of the field, she wrote, were good reminders of the teachings of Christ. And she deplored the fact that so little effort was being made to record native plants before they vanished “as civilization extends through the Dominion.”

Studies of Plant Life in Canada

appeared in 1885, a couple of months before Catharine travelled down to Toronto to sit with her dying sister. The book's reception lightened Catharine's mood as she watched Susanna's steady decline and heard her sad, unhappy rantings. The Toronto

Globe

wrote of Catharine's publication: “There is in it enough of technicality to make it extremely useful to the student, while there is about it a literary charm that will lead even the reader most ignorant of botany to go through that book from one end to the other.” The

Week

acknowledged Catharine as “an authority upon the flora of this country” and praised her for her “simplicity of style.” The Marquis of Lorne, who had been Governor-General of Canada from 1878 to 1883, and to whom the book was dedicated, told Agnes Chamberlin that Catharine's work “will add a great deal to our pleasure in discerning the different species.” And Professor Fletcher wrote her: “With regard to your disclaiming the title of botanist, all I can say is, I wish a fraction of one percent of the students of plants who call themselves botanists, could use their eyes half as well as you have done. I think indeed your work of describing all the wild plants, in your book, so accurately that each one could have the name applied to it without doubt, is one of the greatest botanical triumphs which anyone could achieve, and one which I have frequently spoken of to illustrate how one can develop their powers of observation.”

Catharine knew how she wanted her “little work,” as she called it, to be regarded. She opened with a verse from Sir Walter Scott, and she addressed her “dear reader.” In the introduction, she stated that she hoped the book might become “a household book, as Gilbert White's

Natural History of Selborne

is to this day among English readers.” White's eighteenth-century classic was an anachronism to muscular post-Darwinian botanists at the turn of the nineteenth century. Yet Catharine always understood the book's gentle appeal, based on literary as well as scientific merit. Had

Studies of Plant Life in Canada

been received as a literary rather than a scientific text, it might have been seen alongside works by contemporaries who shared her concerns. Catharine Parr Traill would have been comfortable in the company of the nineteenth-century American poet Walt Whitman, who wrote, “A morning-glory at my window satisfies me more than the metaphysics of books,” or the Russian writer Anton Chekhov who, in

Uncle Vanya

, bemoaned the fact that, “Whole Russian forests are going under the axe. â¦We're losing the most wonderful scenery for ever, and why?”

Studies of Plant Life in Canada

, however, was assessed not as a literary work but alongside straightforward field-guides. It had a short shelf-life: it was reprinted in 1906, then virtually forgotten.

In the short term, Catharine's age alone gave

Plant Life

a novelty value that led to sales. Most octogenarian authors would have regarded this triumph as their last hurrah and retired to rest on their laurels. But Catharine couldn't. Her impulse to tell the next generation of Canadians about the natural beauty around them remained unquenched.

Chapter 20

The Oldest Living Author in Her Majesty's Dominion

C

atharine was seated in her favourite rocking chair near the French windows of Westove's parlour. From this vantage point, she could look out at the lilacs in her garden and watch the plump Canadian robins strutting about on the grass. On one side of her chair was a sewing basket, filled with brightly coloured scraps of fabric from which she was making a patchwork quilt for the Indian Missionary Auxiliary. On the other side was a knitting bag, in which was tucked a half-finished woollen hat for one of her grandsons. Today, however, Catharine was busy with the activity she most enjoyed of all her pursuits: writing. On her lap was a portable writing desk, with a fresh sheet of paper and an inkwell filled with thick black ink. Her steel-nibbed pen hovered over the page as her mind drifted back to her Suffolk childhood.

She was trying to capture in words the atmosphere of Reydon Hall in the early years of the century, when she and her five sisters were

growing up there. In 1887, her sister Jane Margaret Strickland had published

Life of Agnes Strickland

. Jane's book was an adulatory account of her sister's biographical achievements, describing Agnes in glowing terms as a sort of literary Madonna: “We must remember that Agnes Strickland was really more of the woman than the author. She had a feminine love of dress and female employments, was fond of fine needlework, and, till she had a maid, mended her own stockings.” Jane's biography of Agnes received some cruel reviews.

The Athenaeum

announced that it was “one of those books which might as well not have been written â¦[the author] is perpetually reminding us of the number of balls to which her sister was taken, the number of country houses which she visited, and the number of genteel persons who drove her out in their own carriages.” Jane's loving, but banal, memories of her dauntingly intelligent older sister provided an excuse for Agnes's male rivals to dismiss her achievements with misogynist glee. “We have not yet arrived,” sniffed

The Northern Whig,

“at that stage of evolution when women can rank as historians of the first order.” Jane was crushed by these comments. Her health, already poor, suffered. Within a few months, she was laid in a grave next to Agnes's splendid marble monument in the graveyard of St. Edmund's Church, Southwold.

Catharine didn't want to belittle Agnes's leather-bound royal biographies. She was too fond of Jane, and had too much experience herself of misogynist brushoffs from professional men, to reply to these unkind reviews on Jane's behalf. However, she was saddened by Jane's book because Jane had scarcely mentioned either Susanna or Catharine herself. Samuel Strickland was allowed a walk-on part as the author of

Twenty-seven years in Canada West,

“which contains everything necessary for a settler to know.” But there was no reference to the literary achievements of Agnes's youngest sisters, who had written much better, more helpful books about Canada. Catharine wanted to record a fuller picture of the gifted Strickland family.

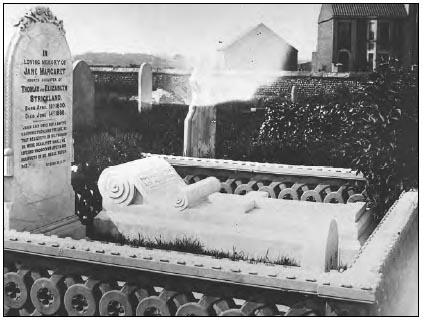

Agnes and Jane Strickland's gravestones in the graveyard of St. Edmund's Church, Southwold. A great-niece of Catharine sent her this picture.

Scratch, scratch, scratch ⦠the steel nib started moving quickly across the page. Catharine had always been a fluent and fast writer, and old age had not slowed her down. “We passed our days,” she wrote, smiling at the Reydon memories, “in the lonely old house in sewing, walking in the lanes, sometimes going to see the sick and carry food or little comforts to the cottagers; but reading was our chief resource.” Catharine enjoyed penning these “pictures of old world life,” as she described them to one publisher, “which will amuse if not astonish the reader taking him back into bygone scenes even to the past days of the former century ⦔ At the other end of her own lifetime and on the other side of the Atlantic, she acknowledged that she and her sisters had been part of an extraordinarily rich literary tradition, a uniquely Old World legacy which she had absorbed, and of which her own children and grandchildren had no notion. Before Thomas Strickland's death, the household at Reydon Hall had included servants to cook, clean, launder, press, garden, dust, sweep, preserve and bake. Thomas's young daughters had the time to furnish their minds from his library. Catharine scribbled down her memories of

how they had penned historical dramas, “embellished according to the invisible genius of their fertile minds,” and “ransacked the library for books.” She described how Agnes, when only twelve, could recite from memory whole scenes from Shakespeare and lengthy passages from Milton's

Paradise Lost.

She smiled as she remembered how she had thrown herself into the role of Ariel in a Reydon Hall production of

The Tempest.

Scratch, scratch, scratch ⦠the pen moved faster and faster as memories flocked back. Catharine recalled how Elizabeth had excelled at quick sketches of village characters, including John Fenn the rat-catcher, old Catchpole the mole-catcher and “some old women reputed to be witches but really very harmless creatures.” She wrote of Jane's cloud of curls and Sarah's sense of style: “When dressed in her riding habit and Spanish hat and feathers she certainly made a striking appearance.” But the sister she recalled with the deepest and most familiar affection was the one to whom she had always been closest.

It was more than five years since Susanna had died, and Catharine missed her. These days Catharine remembered her sister not as the cantankerous widow or the demented old woman on her deathbed, but as the lively, headstrong girl with “an inherent love of freedom of thought and action.” She wrote about her with a love and longing she had never expressed about Thomas Traill after his death. “We two lived in childlike confidence and harmony, as we grew up side by side as loving friends, our lives remaining in parallel grooves, and this continued even after we married and left the old home at Reydon to share the untried fortunes of the new world in our forest homes in what is now Ontario.” In particular, she remembered her youngest sister's intensity. “Susie was an infant geniusâ¦. Her facility for rhyme was great and her imagination vivid and romantic, tinged with gloom and grandeurâ¦.As is often found in persons of genius, she was often elated and often depressed, easily excited by passing events, unable to control emotions caused by either pain or pleasure. â¦I was not of so imaginative a disposition.”

Whatever wistful thoughts of Susanna she harboured, Catharine undoubtedly comforted herself with the pleasure she continued to take

in her own huge family. Five of her seven children were still alive in 1890, and she had twenty-one grandchildren. Kate Traill continued to look after her mother, and Annie Atwood and Mary Muchall, Catharine's two married daughters, lived close by. But both her sons, like so many young men in the late nineteenth century, had been forced to travel west in order to find work. William and Walter were now both settled in western Canada and had started families thousands of miles away from Lakefield. Catharine ached to see them and her “little Nor'wester grandchildren.” Even when her right hand was swollen with rheumatism, or her eyes cloudy with cataracts, she managed to write them lengthy letters. “See dear how I have blotted the sheet well you must not mind the blot but take from the hand of the aged mother,” she wrote to William Traill, now a chief trader dealing in furs for the Hudson's Bay Company in the remote northwest of the Dominion. William wrote affectionate letters home, filled with vivid descriptions of native uprisings, natural disasters and adventurous canoe trips. He sent his mother dried ferns and grasses from the Peace River region. But Walter's letters arrived infrequently these days, and were often gloomy. Catharine confided to William her concerns about Walter's mental health. “I fear for that morbid temperament so like his dear father's.”