Six Women of Salem (34 page)

Read Six Women of Salem Online

Authors: Marilynne K. Roach

Tags: #The Untold Story of the Salem Witch Trials

This day other prisoners also facing the court and the noisy afflicted witnesses included Mary Toothaker, wife of jailed folk healer Roger Toothaker, and their nine-year-old daughter, Margaret; Captain John Flood, a militia leader even less successful than Alden; and William Procter, the seventeen-year-old son of John and Elizabeth Procter. Constable John Putnam had brought in the Procter boy.

According to Thomas Putnam’s list of those afflicted as of May 28, William Procter’s specter had tormented Mary Walcott and Susanna Sheldon “& others of Salem Village.” Precisely what Mary Warren, herself still suspected by the other girls, did and said during William’s questioning is, unfortunately, lost, as is how William felt toward her and who among his brothers might have dared be in the audience. Although their household had not been without conflict before, they must have been united in resenting her for helping to rupture the family so thoroughly.

The surviving paperwork indicates that William’s specter tormented Mary Warren and Elizabeth Hubbard, who most distrusted Mary, presumably during questioning. William refused to confess, and the court then took the unusual move of tying him neck and heels, a military punishment that drew the prisoner’s head down toward his bound feet. As John Procter would write,

My Son

William Procter

, when he was examin’d, because he would not confess that he was Guilty, when he was Innocent, they tyed him Neck and Heels till the Blood gushed out at his Nose, and would have kept him so

24

Hours, if one more Merciful then the rest, had not taken pity on him, and caused him to be unbound.

All of those questioned were held for trial, including an Arthur Abbott, who lived “in a by place” near Major Appleton’s farm on the border area of Ipswich, Topsfield, and Wenham. Though “Complained of by Many,” his sparse case notes suggest that he, like Mary Esty, would be set free in the near future. Unlike her but like Nehemiah Abbot (no relation), he would apparently remain free.

Before the magistrates left the Village Mrs. Ann Putnam submitted a deposition that Thomas had written out for her. In it she related how Rebecca Nurse’s specter began to torture her from March 18 onward. Martha Corey’s specter was just as bad, nearly tearing Ann to pieces, attacking with “dreadfull tortors and hellish temtations,” urging her to sign her soul away “in a litle Red book” with “a black pen.” But the tortures Nurse inflicted “no toungu can Express.” On March 22, when Nurse had appeared in her shift, “she threatened to tare my soule out of my body blasphemously denying the blessed God and the power of the Lord Jesus Christ to save my soule.” Ann was also tormented on March 24, especially during Rebecca’s examination, so “dreadfully tortored . . . that The Honoured Majestraits gave my Husband leave to cary me out of the meeting house,” allowing her to recover. And that had ended the specters’ power to hurt her.

Just having to talk about it again was distressing. As a court official read her words back to her prior to her swearing to them, she became overcome and convulsed—right in front of the magistrates, in front of her daughter. It was Nurse’s vengeful specter attacking her—Nurse, her great enemy. Yes, said Annie. It

was

Goody Nurse, and Goody Cloyce and Corey too—all attacking her mother.

Samuel Parris, having taken most of the day’s examination notes, added to Ann’s deposition. She had not been troubled since Goody Nurse’s hearing “untill this 31 May 1692 at the same moment that I was hearing my Evidence read by the honoured Magistrates to take my Oath I was again re-assaulted & tortured by my before mentioned Tormentor Rebekah Nurse.”

Francis Nurse, however, was busy gathering signatures on a petition verifying Rebecca’s good character. In part it stated, “Acording to our observation her Life and conversation was Acording to hur profestion [of Christianity] and we never had Any cause or grounds to suspect her of Any such thing as she is nowe Acused of.”

Thirty-nine neighbors signed, with Israel and Elizabeth Porter (Hathorne’s sister), who had visited in March, among the first. Eight Putnams signed, including John and Rebecca Putnam, whose baby had died mysteriously. Daniel Andrews, another of the March visitors, had also signed, but he had already fled some weeks before after being accused himself, so how useful the document would be was in question.

The other prisoners from Salem in Boston’s jail would resent Tituba for her confession—Tituba, the catalyst, whose lies had helped get the rest of them in so much trouble. Did any of them empathize with her impossibly difficult situation? Or did they keep their distance, marking out territory in the big common room? Some were chained down and had no choice. Perhaps Tituba associated with the other nonwhite woman in that place, with Grace, a slave under a death sentence for infanticide. In the long, endlessly boring days and sleepless nights Tituba and Grace might have shared stories of their past lives. If so, Tituba would have learned how Grace, working in Boston as the property of the province’s treasurer, had born a child—alone, in winter—dragging herself to the backyard privy for privacy. Then, once rid of the burden, she jammed the infant headfirst down the privy hole. That was where someone had found the tiny body. Grace was arrested for murder, tried and convicted. Yet with no charter and the government in limbo, she could not be executed. The local government would not presume so far until they knew what England expected of them. So Grace languished in the Boston prison for years, she and Elizabeth Emerson, a young unmarried white woman from Ipswich who had born twins who were later found dead, sewn in a sack and buried in her parents’ garden. Elizabeth told the authorities that they were born dead, but something about the bodies suggested otherwise. She too was found guilty of murder and awaited execution. Now that the government was being re-formed—enough for the courts to try the witchcraft cases—death sentences could be brought against Elizabeth and Grace as well.

The court records do not indicate whether Grace had conceived the child from a consensual act or from rape, nor did it say if she killed the infant as an unwelcome reminder of the rapist who had sired it or killed the child to free it from a life of slavery and humiliation. Perhaps Tituba learned.

____________________

More and more suspected witches have been sent from Salem to Boston’s jail. Tituba is surprised that so many respectable women are among them—or at least women whom neighbors had once regarded as respectable. Even church members and those women of wealth and prestige were here alongside poverty-stricken Sarah Good. Mistress English has servants who bring changes of clean linen. Others, like Goodwives Nurse, Esty, and How have devoted families who make the long journey to visit. It takes the horses more than half a day to cover the distance from Salem to Boston. Others must hope for the sparse help of strangers.

A few brave folk venture to visit, usually armed with spiritual comforts instead of the practical necessities so desperately needed. Others send a servant to do so, a more convenient way to store up credit in Heaven.

At the least it breaks the monotony to watch them. Tituba notices Sarah Good begging a bit of tobacco from a nervous hired girl who is trying not to look any of the suspects in the eye. Clearly she does not want to be there.

Sarah, already more on edge than usual since the death of her infant, raises her voice to repeat the request, but doing so makes it sound like an order.

The girl panics, snatching a handful of the dirty wood shavings from the floor. “That’s Tobacco good enough for

you!

” she shouts, throwing the filthy remnants into Good’s face.

Sarah erupts in an enraged spate of ill words that terrifies the maid even more, sending her running to the guard to be let out.

The suspected witches are a fearful class of prisoner to most of the population, though this prisoner class clearly makes its own distinctions—Tituba and Good apart from Nurse and Esty, all apart from Cary and English. Later, word trickles back that that girl has become as wracked by fits as any in Salem.

Tituba is not surprised. When the mischievous and malicious run free, aren’t we all, both high and low, enslaved by other’s whims?

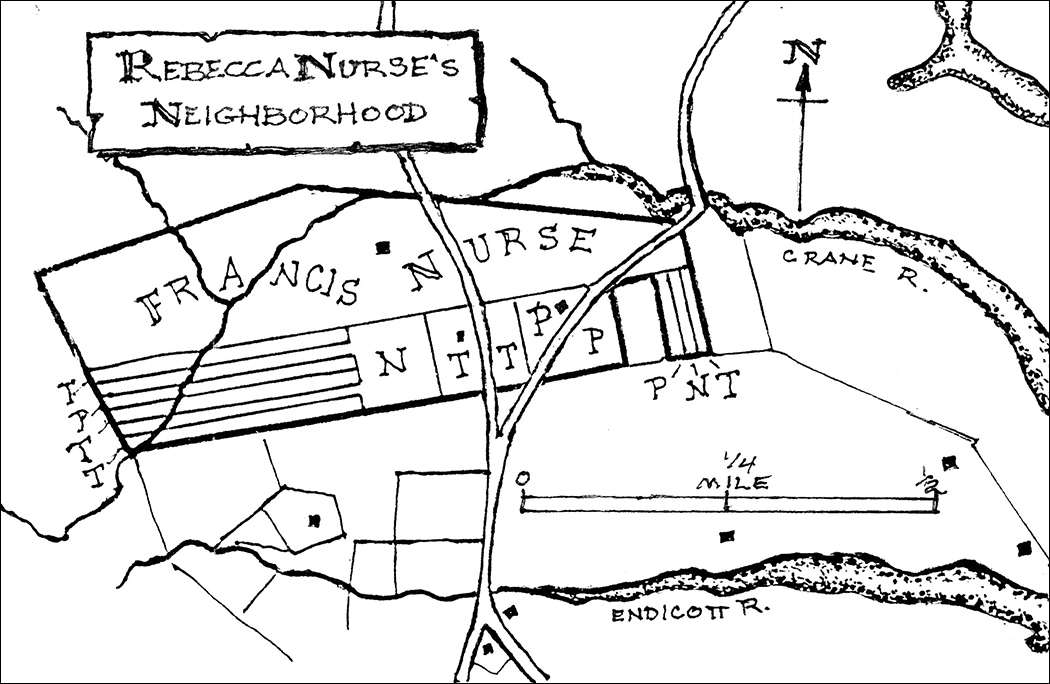

Francis and Rebecca Nurse’s Neighborhood. Francis Nurse divided about half of his farm in 1690 and parceled the various lots to his son Samuel Nurse and sons-in-law John Tarbell and Thomas Preston. (Map by the author. Source: Perley, “Endicott Lands, Salem in 1700.”)

N Samuel Nurse

T John Tarbell

P Thomas Preston

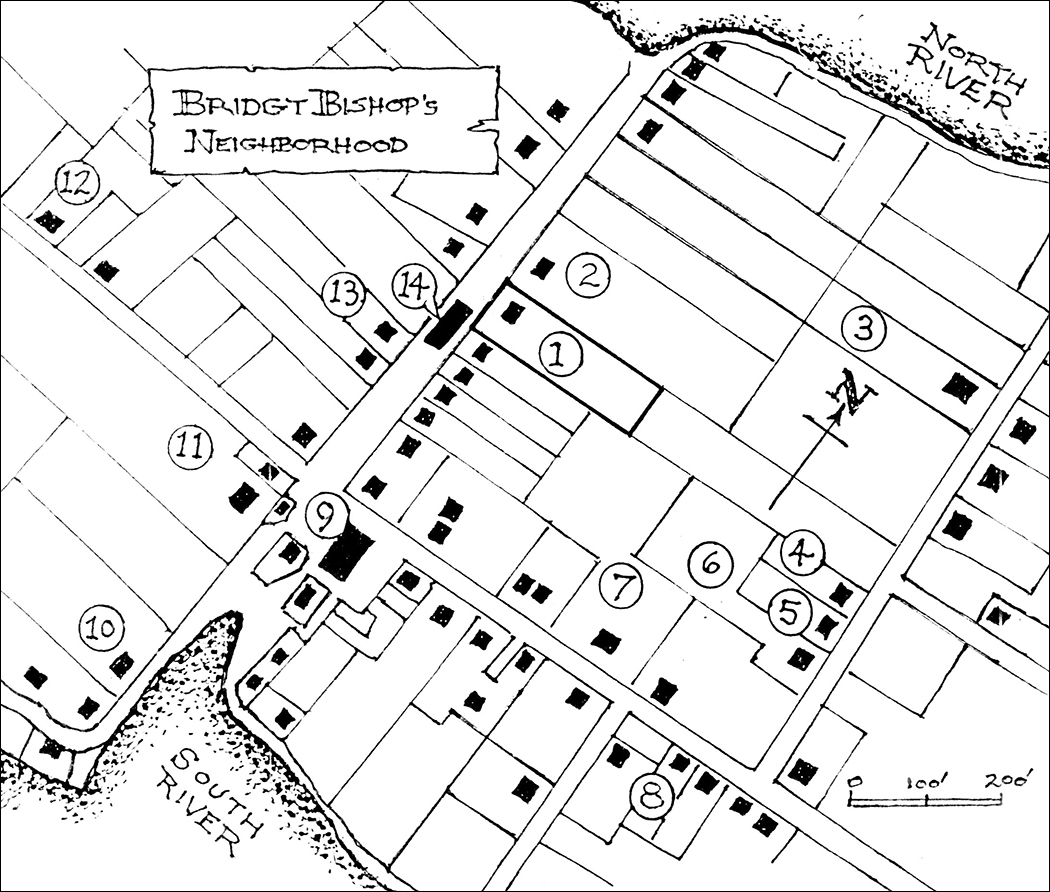

Bridget Bishop’s Neighborhood. (Map by the author. Source: Perley, “Part of Salem in 1700,” Nos. 1, 2, 3, 14, 15, 28.)

1. Edward and Bridget Bishop, the Thomas Oliver estate.

2. Daniel Epps, schoolmaster.

3. Jail.

4. Samuel Beadle, tavern.

5. Robert Gray, said he was tormented by Bridget’s specter.

6. John Burton, surgeon, examined Bridget and other suspects for witch marks.

7. Ship Tavern.

8. Samuel Shattuck, said Bridget bewitched his son.

9. Salem Meeting House.

10. Sheriff George Corwin.

11. John Hathorne, magistrate and judge of the Court of Oyer and Terminer.

12. Stephen Sewall, clerk of the Court of Oyer and Terminer.

13. Reverend Nicholas Noyes.

14. Town House, scene of Oyer and Terminer trials.

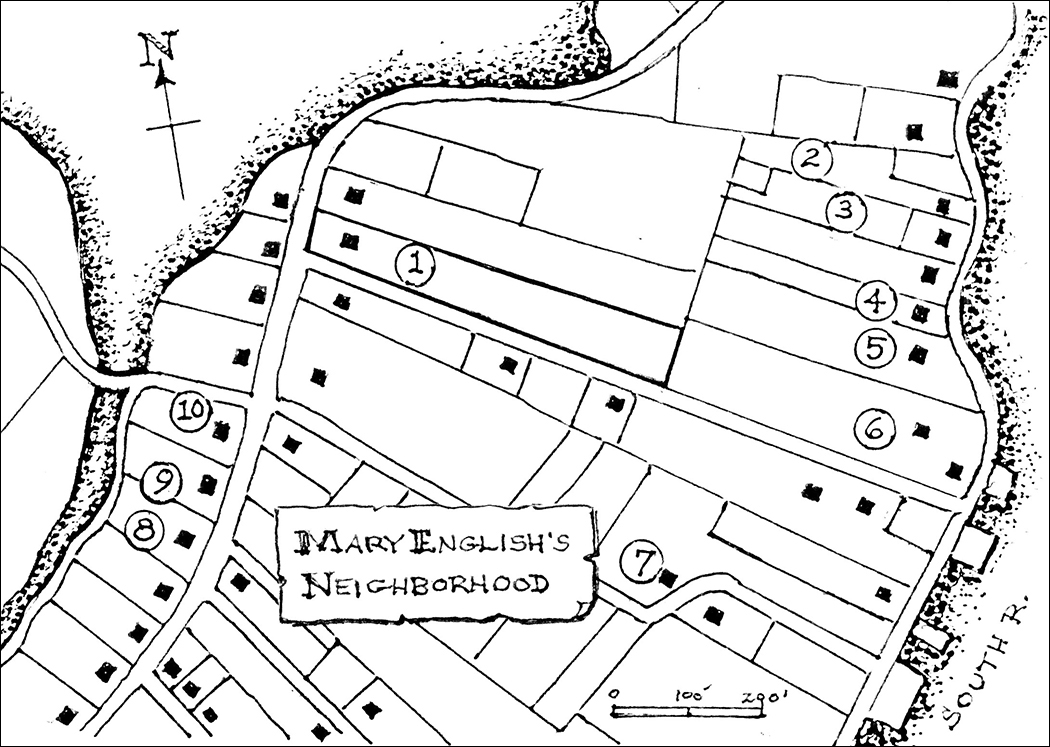

Mary English’s Neighborhood. (Map by the author. Source: Perley, “Part of Salem,” Nos. 21, 23, 22, 23.)

1. “English’s Great House,” Philip and Mary English.

2. Walter Whitford, fisherman, died 1692.

3. John and Bridget Whitford. John also died 1692. Whitford is presumably the same as Whatford. A distracted Goodwife Whatford said the specters of Bridget Bishop and Alice Parker tormented her.

4. William and Elizabeth Dicer here 1668to 1685 when William sold the lot to Philip English and moved to Maine. Elizabeth called Eleanor Hollingworth a witch in 1679 (and would herself be accused in 1692).

5. Fisherman John Parker and wife Alice rented this house. Originally owned byWilliam Hollingworth, it passed to his daughter Mary English, and then to Philip English.

6. Blue Anchor Tavern, operated by Eleanor Hollingworth in her home, deeded to her daughter Mary English in 1685, descended to Mary’s son John English Jr.

7. In 1735, John Beckett inherited half of the family home and purchased the remainder for himself and his wife Susanna (Mason) Beckett.

8. Rental property owned in 1662 by Eleanor Hollingworth, then by her sonWilliam who sold it. A few owners later, Philip English bought it in 1675 and later willed it to his daughter Mary (English) Browne.