Six Women of Salem (36 page)

Read Six Women of Salem Online

Authors: Marilynne K. Roach

Tags: #The Untold Story of the Salem Witch Trials

Gravestone for Mary English’s brother William Hollingworth and their mother Eleanor Hollingworth, Charter Street Burial Ground, Salem, Massachusetts. (Photo by the author.)

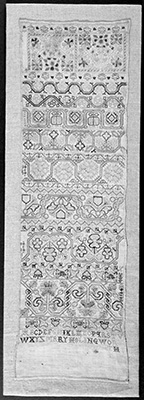

Mary Hollingworth’s sampler, c. 1665. (Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA.)

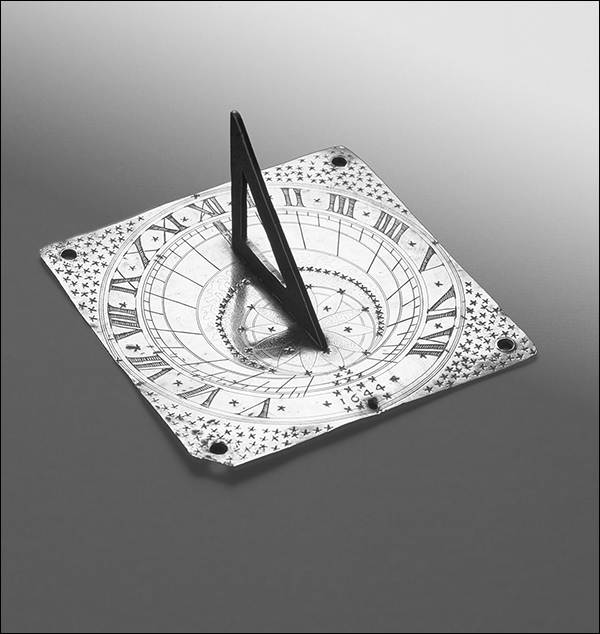

John Procter’s brass sundial, dated 1644. (Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA.)

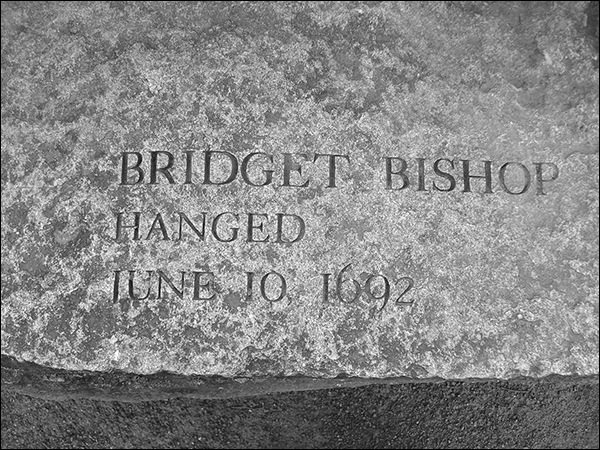

Bridget Bishop’s name carved into the Witch Trials Memorial, Salem, Massachusetts. (Photo by the author.)

Cloth poppet reportedly found walled into the brickwork of afirst period house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, on loan to theWitch House/Corwin House, City of Salem. This wasprobably meant to be a protective charm, unlike the pin-studded poppets supposedly found in Bridget Bishop’s cellar.(Photo by the author. Used courtesy of the City of Salem.)

Putnam tomb, Putnam Burying Ground, Danvers, Massachusetts. The unmarked mound in the foreground is the site of the tomb. (Photo by the author.)

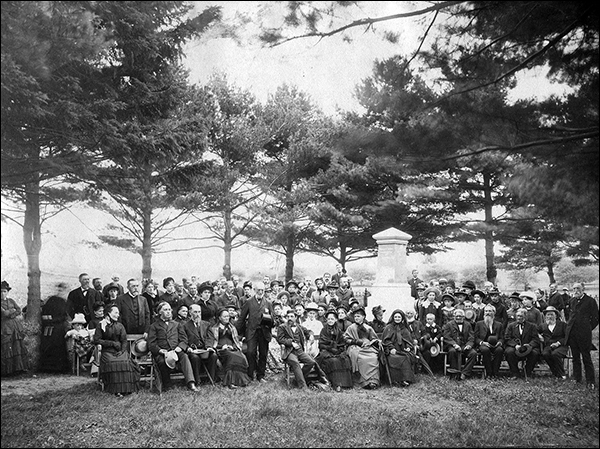

Dedication of the Rebecca Nurse Monument on July 30, 1885. (Photocourtesy of Danvers Historical Society.)

(

9

)

1

to

9

,

1692

Mistress Mary English, surveying the Boston jail’s common room, notices that something is afoot in the bustle of the guards and the tension of the prisoners. Court would sit soon—at last, after years of suspension—though no one quite knows whether or not that is good.

The new justices are men of influence responsible for the public’s safety. Yet considering the evidence brought against the accused—against herself—at the hearings, could those men

truly

discern what had and had not happened? Some of the Salem magistrates are part of the new court, and their acceptance, so far, of what the witnesses say is far from encouraging. The court must be informed of the true situation. The Nurse kindred thinks so too, having collected an impressive number of names on Rebecca’s behalf. The justices are reasonable men, aren’t they? Usually reasonable, anyhow, even if Hathorne and Corwin get carried away by the noise and fits.

Soon the heavy door rattles open, and the jailer, John Arnold, enters with a document. Certain prisoners, he announces, will be transferred to Salem to stand trial, moved out today—now. The prisoners have been expecting this, yet the moment still sends a shock of fear through the room, with their desire for something to break the monotony warring with trepidation.

Bridget Bishop, the officer calls, Susannah Martin, Rebecca Nurse, Sarah Good, Alice Parker, Tituba, John Willard, John and Elizabeth Procter.

Not yet,

Mary English thinks.

Not this time.

She watches the leave-takings wondering when—and under what circumstances—she will see Philip again. The guards have told her of his arrest.

Rebecca bids farewell to her sisters Mary Esty and Sarah Cloyce.

The Procters part from son Benjamin, Elizabeth from her sister Mary DeRich and sister-in-law Sarah Bassett. John murmurs some sort of fatherly advice to Benjamin, the words lost in the room’s commotion.

No one mentions it, but all know they might never see each other again in this life.

The jailer’s men move among them, unlocking the chains from the wall, levering the elderly and unsteady from the floor, where they have sat for so long.

The guards part Sarah Good from her daughter, the mother protesting, struggling, and the child wailing at this additional loss, frantic to join her mother but left behind all the same.

The door thuds shut at last, and the bolts clank into place.

Dear God,

thinks Mary.

What next?

____________________

L

ed, shuffling and clanking into the daylight, into a fresher breeze of salt air from the harbor after the closed-in fetor of the common room, hearing the sharp cries of gulls, most of the prisoners would be hoisted into a cart, John Procter likely insisting on helping Elizabeth. Tituba, as a repentant witch, was being treated as a potential witness. Newton had sent orders for her to be kept apart from the others, so perhaps she rode on a pillion behind one of the mounted officers. The procession left the stone jail, and as they headed to the ferry at the north end of Boston’s peninsula, they could probably hear Dorothy Good’s muffled wail, the child’s cries fading as the party threaded the narrow streets to the ferry wharf.

Once across the mouths of the Charles and Mystic Rivers, they began the journey through and around the great stretch of marsh that hummed this time of year with mosquitoes, unless the wind favored them. Partway though the trip the party encountered another cavalcade heading south, men on horseback with another wagonload of people—the latest batch of prisoners assigned to Boston. The groups would pause while the guards conversed, exchanging news and gossip of the latest suspects, the goings-on in court. From the wagons the prisoners could eye each other, the Procters recognizing their son William in the other cart headed for the Boston jail, as he saw his parents heading for trial and, after that, who knew what.

Philip English was in the cart as well and would reach Boston prison after the long, tiring trip, entering the stone jail where his wife awaited him.

But Mary English did not wait idly. On June 1 she and Mary Esty, with Edward and Sarah Bishop, submitted statements regarding Mary Warren’s testimony, determined to tell the court just what sort of “evidence” was being given against them. All four had been present in the Salem jail when Mary Warren explained that her visions had been only distraction—distraction or the Devil’s delusions, the four knew. Not accurate in any case.

Certainly

not accurate.

Prisoners could acquire ink, pens, and writing paper from visiting relatives (or servants), or obtain such supplies from the jailer for a fee. The Bishops and Goody Esty appear to have dictated their joint statement about the Warren girl to someone else:

Aboute three weekes Agoe . . . In Salem Goale . . . wee Heard Mary warrin severall Times say that the Majestrates Might as well Examine Keysars Daughter that had Bin Distracted Many Yeares And take Noatice of what shee said as well as any of the Afflicted persons . . . [Warren said] when I was Aflicted I thought I saw the Apparission of A hundred persons for shee said hir Head was Distempered that shee Could Not tell what shee said . . . [and] when shee was well Againe shee Could Not say that shee saw any of the Apparissions at the Time Aforesaid.

Mistress English was none too sure about these Bishops, what with that raucous, illegal tavern of theirs, not since her desperate cousin—one of the Bishop’s long-suffering neighbors—cut her own throat after trying to reason with them. However, she and they agreed about Warren. In any case she was quite capable of writing her own statement. Looping the letters across the paper and signing it at the end, she wrote,