Skywalker--Highs and Lows on the Pacific Crest Trail

Read Skywalker--Highs and Lows on the Pacific Crest Trail Online

Authors: BILL WALKER

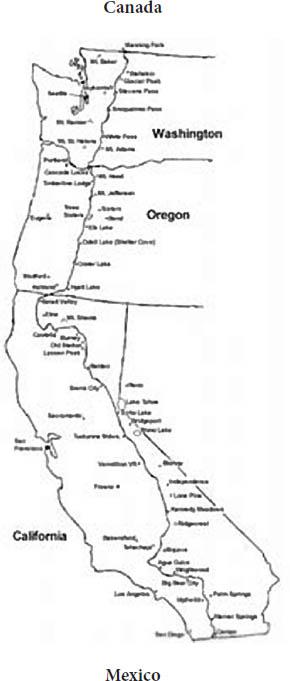

SKYWALKER

HIGHS AND LOWS

ON THE PACIFIC CREST TRAIL

By Bill Walker

eBook ISBN: 978-1-62112-206-7

My mother, Kathleen Malloy Walker, who has

never given in to the surely strong temptation to

crane her neck up at me and cry out in horror,

“What hath I wrought?”

This book describes the author’s experiences while walking the Pacific Crest Trail and reflects his opinions relating to those experiences. Others may recall these same events differently. Some names and identifying details mentioned in the book have been changed to protect their privacy.

Contents

Chapter 2: Why Long-Distance Hiking?

Chapter 3: The Pacific Crest Trail

Chapter 9: Caches, Ledges, and Trail Repartee

Chapter 17: Final Desert Surprises

Chapter 21: Scott Williamson PCT Superstar

Chapter 22: CanaDoug—Snow Maven

Chapter 24: Three’s Not the Charm

Chapter 25: Scottish-American Beacon

Chapter 26: “Worst Bug Day in PCT History”

Chapter 27: The ‘Root Canal’ Aspect of Hiking

Chapter 29: Donner’s (Dahmer’s) Pass

Chapter 30: Northern California Tales—Psychological Crucible

Chapter 32: The Art of the Possible

Chapter 33: California Leavin’

Chapter 34: An Eastern Man of the West

Chapter 38: The Corps of Discovery

Chapter 39: The Evergreen State

Chapter 40: The Northern Cascades

Chapter 41: Northwestern Hospitality

Chapter 42: Splendid Isolation

The most beautiful adventures are not those we go to seek.

Robert Louis Stevenson

“I

s this the worst you’ve ever been lost hiking?” Lauren suddenly asked me.

It was the afternoon of July 3, 2009. All across America people were heading off in packed cars to barbecues, beaches, and sunny vacations to celebrate the upcoming Independence Day holiday. Lauren and I, however, were confronted with a stunningly contrarian scene. All we could see, for miles on end, was a heavy blanket of snow interspersed with frozen mountain lakes. The last few miles had been up to our waists, at times.

Lauren was seventeen years old, and we were hiking together completely by accident. Her mother had heard from a co-worker that his son was planning a hike on the Pacific Crest Trail. Because Lauren had shown some nascent interest in hiking, her mother had inquired—perhaps against her better judgment—about the possibility of Lauren joining her co-worker’s son. That had led directly to this mess.

Weeks earlier Lauren had joined up with this proposed hiking partner. His name was Pat, and he was a 26-year old male of extraordinary athletic ability. The two of them had set out together on the hardest part of the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT). It is called the

High Sierra

and reaches the very highest points on the American mainland. By everyone’s appraisal, Lauren and Pat were making a game effort.

Having a hiking partner allowed them to share several items, including a tent. This critically reduced their backpack weight. However, because they slept in the same tent, there had been some murmurings on the trail grapevine about Pat trysting with the 17-year old Lauren. But I had seen them up close for several days and nights running, and it seemed all business. All about miles.

A hiking partner also reduces one’s chances of getting lost. Theoretically. But Pat was perhaps the fastest hiker I had ever seen, despite having a backpack that looked like it was loaded down with sandbags. He appeared so rhapsodic about hiking in this magnificent mountain setting that I had begun to think he was afflicted with the Icarus complex. Pat habitually blasted off ahead of Lauren first thing in the morning. She repeatedly sacrificed breaks, hiking for hours-at-atime, (earning her the trail name,

No Break

) to keep up with him. One could objectively say she was being courageous.

At the end of the day, when Pat and Lauren were finally reunited at some distant campsite, he often had a slightly embarrassed look on his face—like he couldn’t help himself. Maybe he couldn’t. Like so many mortals who had preceded him over the eons, he was utterly in the thrall of the High Sierra.

Long-distance hiking is inherently conducive to mood swings. But on this 3d day of July, my morale was especially fragile. The previous night I had camped alone, about a half-mile ahead of Pat and Lauren. I had gotten up this morning at first light prepared to clear Muir Pass, the last really difficult, snowy pass in the

High Sierra.

For days I had been anxiously debriefing south-bounders passing in the opposite direction about what exactly lay ahead. One after another had reported that the Pass was covered with a thick blanket of snow for miles on each side of the summit.

Not surprisingly, soon after I began trooping this morning, Pat had come jackrabbiting past me.

“Wait for Lauren and me,” I yelled ahead to him playfully.

“Yeah, yeah,” he said self-consciously. “I’ll, uh, see you up at the top.”

Yeah, sure!

The biggest problem was simply figuring out where to go. The vast amounts of snowmelt had created more surging streams than I could have ever fathomed. This morning I had been able to follow Pat’s footprints through the snow along the western edge of a couple of alpine lakes. But as the PCT started up the face of Muir Pass, the placid lakes and footprints gave way to the heavy rush of water crashing down a ravine. I saw footprints on the far side, which meant I needed to somehow get across.

Tentatively, I edged down the icy bank to get to a large rock. But my feet came out from under me, and I did a base-runner’s slide right into the icy running water. I frantically thrashed around attempting to reach the next icy boulder. I didn’t completely careen over, but splashed wildly the last several feet in the rushing current getting to the far side.

At least I’m over.

When I looked back down the hill I spotted Lauren, scoping around trying to decide on a route. Instinctively, I started waving her to come up my way. Lauren dutifully followed my footprints up the left bank, and soon stood at the precipice of the tumbling rapids.

“Here, here” I kept shouting. She looked dubious. For good reason. The spot I was pointing out was shallower, but the current even stronger.

“Right there, there,” I kept shouting over at her. “That rock.” Finally, we gave up any cross-stream communication, as she hung in suspense atop a jagged boulder, plotting her next step. Water roared by her on all sides, and she took on plenty of it. But soon enough she, too, was across.

“Good goin’,” I tried encouraging her. “We’ll stick together until we catch up with Pat.”

“Alright.”