Something to Declare: Essays on France and French Culture (27 page)

Read Something to Declare: Essays on France and French Culture Online

Authors: Julian Barnes

When Flaubert wrote to George Sand in 1866 that “I am sometimes truly bothered by how bourgeois I am beneath my skin,” he was partly trying to defuse Sainte-Beuve's judgement on him as “depraved.” But the years 1859–68 show Flaubert more than ready to exploit the advantages and connections of his place in the upper bourgeoisie, to use his influence, push friends, play the system. This is normal—even

de rigueur

—in French literary life; but Flaubert also had no compunction about nobbling Rouen judges, or putting a word in with Princesse Mathilde to help the husband of a friend of Caroline's get promoted

chef de bataillon.

And when it came to Caroline herself, the bourgeois within him lay very close beneath the skin. He adored her; he brought her up to value the artistic life; he urged her to avoid the un-joined-up thinking he found characteristic of her sex, and paid her the highest compliment of writing to her “as if to a sensible young man.” But when the lessons of her artistic upbringing looked like they were being applied in real life—when, still only seventeen, she fell in love with her art teacher Johanny Maisiat, a man twenty-two years her senior and manifestly lacking a fortune—Flaubert conspired with his mother to marry her off to Ernest Commanville and into social safety. Decades later, Caroline wrote in her memoir

Heures d'autre-fois

(still for some reason unpublished), “They suggested a proper, honourable, indeed bourgeois marriage”; as a result of which “I was thrown out of Parnassus.” Mme Flaubert, a tough old bird, was certainly the chief fixer, just as she brusquely paid off Caroline 's banished father when he expressed the unacceptable desire to come to his daughter's wedding; but Flaubert's collaboration, his influence over the effectively orphaned Caroline, was central. In October 1863, two months before the drama, he was recording to Amélie Bosquet his proud loathing of “the assembled cream of Rouen, Le Havre and Elbeuf.” In December he sends Caroline a letter which for all its initial non-advice-giving, tells her plainly that “I would rather you married a millionaire grocer than a penniless great man”; better, he says, to be rich in Rouen than a pauper in Paris. Six days after this he writes complacently to Duplan of the crisis, “Everything will work out in the best bourgeois manner.”

Caroline's sole surviving letter, written while trying to make up her mind on what was proposed, is a touching, naïve document,revealing deep uncertainty and an equally deep desire to please her uncle. She has played music with M. Commanville, she says; he is harmonious in this respect. “But I'm afraid, so afraid of making a mistake. And the idea of leaving you, my poor old uncle, really hurts. But you'll always come and see me, won't you? Even if you found my husband too

bourgeois,

you'd come to see your Liline, wouldn't you? And you'd always have your own room at my house, with big armchairs just as you like them.” No doubt the thoughtful railroading of Caroline into marriage was not so unusual for the time; but she did suffer one extra, humiliating betrayal. Before the marriage Caroline went to her grandmother and explained that she did not want children; Commanville should be informed of her decision and its necessary consequences for him. Mme Flaubert led Caroline to believe that she would square the husband-to-be; but when her granddaughter, dressed in her going-away clothes, found herself in th

e pavillon

at Croisset, alone for the first time with her new husband, she discovered that the bad news had not been transmitted. “My avowal to M. Commanville was harsh and cruel,” she recalled, “and our honeymoon voyage was a sad one.” The marriage was not a success, and Caroline's subsequent life followed the same unfortunate pattern: twice more she fell in love, once more she married, but the two conditions never coincided.

How far should we blame Flaubert? Mlle Leroyer de Chantepie once complained that those who loved her had done her more harm than those who hated her, and this seems to have been Caroline's case; perhaps it always is. Flaubert was certainly in awe of his mother (“So, you are guarded like a young girl?” was Louise Colet's taunt), and the marriage was convenient to him: if Caroline remained in Rouen, she could help him out with mother-care. What the writer wanted most of all from his immediate family was calm. When a dispute arose over Caroline's dowry, he retreated swiftly into the irritable vagueness of the artist who must not be bothered with quotidian concerns. Let everything arrange itself in the best bourgeois manner while he gets on with his work. This might be understandable, and

sub specie aeternitatis

almost forgivable, if he had been writing

Madame Bovary

at the time; but the dismal irony of his role in Caroline's marriage is that the art he needed to concentrate on was that duff

féerie

called

Le Château des coeurs.

The Goncourts' verdict on the play was snobbish but fair. When Flaubert read it to them, they judged it “A work of which we would have judged him incapable, given our opinion of him. To have read your way through every single

féerie

and then produce the most vulgar of all of them …”

Everything did, in a sense, for a time, go in the best bourgeois manner. Caroline wrote comforting letters from her honeymoon implying that all was well. She returned to Rouen and settled into the life of “a fashionable young lady much in demand.” But a breach with her uncle has been opened. Flaubert now begins to rebuke her for being what he had encouraged her to be: an independent bourgeois wife rather than a dependent and adoring niece. He recognizes her new status by using her increasingly as an intermediary in dealing with his mother; but he also finds that she doesn't do what he expects. She comes to Paris when it would be more useful to him if she stayed and looked after his mother. When Commanville is away in Dieppe and he invites her to lunch, she declines. He rebukes her thus:

“Lui, bon oncle pourtant. Lui bon nègre. Lui aimer petite nièce. Mais petite nièce oublier lui. Elle pas gentille! Elle cacatte! Lui presque pleurer! Lui faire bécots, tout de même.”

This retreat into baby-talk, or Little Black Sambo–speak, is peculiar and revealing. By using it, he is seeking to corral his niece back into obedient childhood, but in fact it is he who emerges sounding childish, the whiner not getting his own way.

Caroline continues with the life allotted to her, while Flaubert makes uneasy remarks about her sumptuous carriage and the fact that “Tomorrow Madame is having a big party for all the

grand monde.

Will she even have time to read the love and kisses her poor uncle sends her?” What makes such comments distasteful is that while Caroline is disporting herself with the despised

rouennerie, havrerie,

and

elbeuferie,

Flaubert is simultaneously relaying rather self-congratulatory accounts of his own progress in the truer

grand monde.

He ticks her off for abandoning her study of Montaigne, and in the next letter writes preeningly to her:

“Two

princesses made fun of me.” This is one of the periods from which Flaubert comes out least well. That solitary, plaintive letter from Caroline contrives to haunt a long stretch of the

Correspondance,

and makes the manner of its survival intriguing. Did Flaubert keep only this single letter from his niece? Unlikely. Did he keep all or most of them, and did she then destroy the rest, preserving only this one? And so should we imagine her burning all those cheerful honeymoon lies while saving this true appeal for help, letting it stand thereafter as a rebuke against her famous uncle?

We could not trace Caroline's story so clearly without the extraordinary completeness of the Pléiade edition. Inevitable moments of repetitiousness are balanced by the way we are allowed to follow the life of even a phrase: how “Fuck your inkwell!” (to Feydeau, 1859) becomes “The inkwell is the true vagina for men of letters” (Feydeau 1859) becomes “Drink ink! it makes you drunker than wine” (Feydeau 1861) becomes “Ink is a wine that makes us drunk, let's plunge into dreams since life is so appalling” (Amélie Bosquet 1861) becomes “Let's get drunk on ink, since we haven't got any nectar of the gods” (Bosquet 1861). Or we may watch the creation of an image: when Mme Flaubert is ill in August 1861, Flaubert reports to Caroline that she is given a vesicatory (an irritating ointment or plaster designed to blister the skin—the dying M. Dambreuse is given one in

L'Education sentimentale).

Two days later she is better; two weeks later the writer has appropriated the image to himself, writing to the Goncourts, “My work isn't going too badly. My literary vesicatory brings relief.”

Completeness also allows us to follow the volte-faces, ironic juxtapositions, and quiet hypocrisies that bestrew a long correspondence. Flaubert mocks Michelet in a letter to Gautier, but not long afterwards the historian becomes “cher Maître” (Flaubert also goes into turn-around over George Sand). When Froehner denounces

Salammbô

and also calls it “the illegitimate daughter of

Les Misérables”

we can better imagine Flaubert's double wrath by having read his earlier private trashing of Hugo's book to Edma Roger des Genettes. Equally, the wrong praise can produce a squirm: Flaubert explains to Sainte-Beuve that his approach to antiquity in

Salammbô

is diametrically opposed to Chateaubriand's method; a few months later Maurice Schlesinger innocently congratulates Flaubert on the novel—“People are quite right to compare it to Chateaubriand.” And after reading Flaubert's slightly patronizing teases of Caroline over

le grand monde,

it seems like an act of editorial justice when Bruneau helps us understand the figure the novelist actually cut as he joked with his princesses. The comtesse Stéphanie de Tascher de la Pagerie, for instance, in her

Mon Séjour aux Tuileries

(1894) recalled: “Gustave Flaubert … was showing off amongst us. He has a penetrating glance, but the complexion of a drunkard … His books are heavy-going and so is he.” In 1867, after a ball at the Tuileries which he clearly regarded as a social peak, Flaubert thanks the Princesse Mathilde: “The Tuileries ball stays in my mind like an enchanting dream.” (Comte Primoli, editing this letter, gratuitously inserted the words, “I felt like Madame Bovary, knocked out by her first ball.” A new gloss on “Madame Bovary, c'est moi.”)

The reader of Volume Three can wander constructively among text and notes and variants, letters to and from Flaubert, third-party documents, Goncourt Journals, socio-historical background, plus extensive summaries of books to which Flaubert makes brief allusion, and will constantly be amazed and impressed by Bruneau's rage for perfection. A different sort of rage is in order when considering the obstructiveness and pig-headedness of some owners of Flaubert material. This complete edition could have been even more complete. At the very start of his quest, for instance, Bruneau found ten letters to Ernest Chevalier from the 1830s and 1840s, but couldn't get permission to publish them; there is a similar problem with letters to the comtesse de Grigneuseville. Sadly, it's more than just a case of individual owners harbouring their possessions, aware that an unpublished letter may be twice as valuable as a published one. Bruneau, with what the outsider assumes to be the normal academic altruism, allowed Steegmuller to draw on material as yet unpublished in the Pléiade edition for his second Harvard volume; Alphonse Jacobs, splendid editor of the Flaubert-Sand correspondence, allowed Bruneau to reproduce the whole of his text in the Pléiade edition. The problem lies with Flaubert's letters to his publisher Michel Lévy Bruneau was allowed to reprint in full those which had already appeared in the Conard edition of the

Correspondance.

But every single one of the 102

Lettres inédites de Gustave Flaubert à son éditeur Michel Lévy

can only be represented in the Pléiade edition by their date and their first line. What are the publishers Calmann-Lévy playing at? Protecting the inevitably sluggish sales of a book published way back in 1965 in an edition of 1,500 (of which I bought copy no. 827 in 1985)? Perhaps it is posthumous revenge on Flaubert for the

hauteur

with which he treated his publisher. Whichever way, it is mean-minded and contemptible. It makes you wish Flaubert had been even more eccentric in his negotiating technique and asked how much Lévy would pay for the right not to publish

Salammbô

as well as for the right not to read the manuscript.

(12)

Two Moles

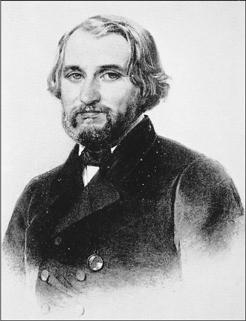

Turgenev at forty: the age of renunciation

Flaubert and Turgenev met on 28 February 1863 at a Magny dinner; the Russian had been brought along by the Franco-Polish critic Charles-Edmond. Recording the event, Goncourt compared Turgenev to some elderly, sweet-tempered spirit of forest or mountain; there was something of the druid about him, or perhaps of Friar Laurence from

Romeo and Juliet.

The Magny regulars awarded him an ovation. In reply, he discoursed on the state of Russian literature, and impressed his hosts with the very high rates paid by Russian magazines. Then the solitary Russian and the several Frenchmen sealed their mutual regard by praising a writer from a third country: Heinrich Heine.