Something to Declare: Essays on France and French Culture (12 page)

Read Something to Declare: Essays on France and French Culture Online

Authors: Julian Barnes

(6)

Tour de France 2000

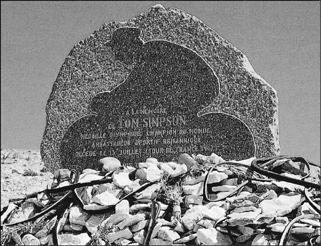

“To the memory of Tom Simpson, Olympic medallist, World champion, British sporting ambassador, died 13th July (Tour de France 1967)”

In early July, as the first Tour de France of the new millennium meandered joustingly down the flat western side of the country, I visited a small cycling museum in the mid-Wales spa town of Llan-drindod Wells. Halfway round this testament to curatorial obsession, among the velocipedes and the 1896 Crypto Front Wheel Drivers, the passionate arrangements of cable clips and repair-outfit tins, there is a small display window containing the vesti-mentary leavings of the British cyclist Tom Simpson. A grubby white jersey with zippered neck, maker's emblem (Le Coq Sportif), big Union Jacks on each shoulder, and discoloured glue bands across the thorax indicating the removal of perhaps a sponsor's name, perhaps the coloured stripes awarded for some previous triumph. Black trunks with peugeot embroidered in surprisingly delicate white stitchwork across the left thigh. Chamois-palmed string-backed cycling gloves with big white press-buttons at the back of the wrist, and the fingers mittenishly cut off at the first joint. This is what Simpson had been wearing on 13 July 1967, during the thirteenth stage of the Tour, when he collapsed on Mont Ventoux, the highest of the Provençal Alps. Thirty-three years to the day of his death, the 2000 Tour was due to climb the mountain again.

Back in 1962, Simpson had been the first British rider ever to wear the race leader's yellow jersey (only three other Britons have acquired it since); he'd been World Champion in 1965, and in 1967 had already won Paris-Nice, the early-season classic flatteringly known as “The Race to the Sun.” He was a strong, gutsy cyclist, popular with fellow riders, the press, and the public. He also played up cheerfully to the Englishman's image, posing emblematically with bowler hat and furled umbrella. The memorial to him near the summit of Mont Ventoux lists his achievements as “Olympic Medallist, World Champion, British Sporting Ambassador,” and the last of these three is no sentimental piety. If sport increasingly becomes a focus for slack-brained chauvinism, it also, at its best, acts as a solvent, transcending national identity and raising the sport, and the sports person, above such concerns. Simpson was one of those transplanted stars (like John Charles in Italy, or Eric Cantona in Britain) who managed to win over a foreign public, and thus did more to harmonize Europe—or at least, reconcile diversity—than a thousand Brussels suits. His martyrish suffering on a French mountain added to the myth. His name is still widely remembered in France—more so, probably, than in Britain.

Mont Ventoux, which rises to just over nineteen hundred metres, doesn't appear especially sharp-sided or rebarbative from a distance. For those on foot, it is comparatively welcoming: Petrarch climbed it with his brother and two servants in 1336, and a local hiking firm offers night-time ascents for the reasonably fit with a promise of spectacular sunrises. For the Tour rider, it is another matter. Other mountains in the race may be higher or steeper, but seem more friendly, or more functional; or at least more routine, being climbed most years. Ventoux is a one-off. Its appearance is perpetually wintry: the top few hundred metres are covered with a whitish scree, giving the illusion of a snowbound summit even in high summer. A few amateur botanists may scour its slopes for polar flora (the Spitzbergen saxifrage, the Greenland poppy), but there is little other recreational activity on offer here. Ventoux is just a bleak and hulking mountain with an observatory at the top. There is no reason for going up it except that the Tour planners order you to go up it. Cyclists fear and hate the place, while the fact that the Tour only makes the ascent once every five years or so increases its mystique, builds its broodingness. In his autobiography,

It's Not About the Bike,

Lance Armstrong called the Tour de France “a contest in purposeless suffering”; the climb of Mont Ventoux illustrates this implacably.

When the tree line runs out, there is nothing up there but you and the weather, which is violent and capricious. Legend has it that on the day Simpson died a thermometer in a café half-way up the mountain burst while registering fifty-four degrees centigrade (officially, the temperature was in the nineties Fahrenheit). But there is one thing cyclists fear as much as heat: wind. One task of the support riders in a team is to protect their leader from the elements; they cluster round him on windy stretches like worker bees protecting the queen. (This abnegation is also self-interested, for in the Tour the monarch is also a cash crop, his prize money being divided among the team at the race's end.) But on the mountains, where the weaker fall away, the top riders are often left to themselves, unprotected. And Ventoux, where the mistral mixes with the tramontane, is officially the windiest place on earth: in February 1967, the world gusting record was set there, at 320 kilometres per hour. Popular etymology derives Ventoux from

vent,

wind, making it Windy Mountain; appropriate but erroneous. The proper etymology—

Vinturi,

from the Ligurian root

ven-

meaning mountain—is duller but perhaps truer. Mount Mountain: a place to make bikers feel they're climbing not one peak but two; a place to give bikers double vision.

*

As I drove towards the mountain the day before the Tour climbed it, there was cloud hanging over its summit, but otherwise the day felt clear, if breezy. This changed quickly on the upper slopes. Cloud covered the top fifteen hundred feet or so; visibility dropped to a few yards; the wind rose. By the side of the road, hardy fans who had arrived early to claim their places were double-chocking the wheels of their camper vans and piling stones halfway up the rims for extra security. The Simpson memorial— the profile of a crouched rider set on a granite slab—is placed where he fell from his bike, a kilometre and a half from the summit on the eastern side. Its handsome simplicity is subverted by the clutter of heartfelt junk laid on the steps in front of it. Some mourners have simply added a large white stone from the nearby slope; but more have strewn the site with a jumble of cycling castoffs: water bottles, logoed caps, T-shirts, energy bars, a saddle, a couple of tyres, a symbolic broken wheel. It is part Jewish grave, part the tumultuous altar of some popular if dubious Catholic saint. All this was difficult to take in because the cold and the wind were pulling so much water into my eyes. It felt locally strange to be attempting some vague act of homage while being barely able to stand; more largely strange in that the winds—gusting at more than 150 kilometres per hour that day—seemed to have absolutely no effect in dispersing the cloud. After a few minutes, I got back into the car and drove down the mountain to Bédoin, where I found that the bones of my fingers and toes still ached from the cold. I craved a whisky. An hour or so later, snow fell on the summit.

When Petrarch set out on his ascent, he encountered, like any modern journalist, a quotable peasant who just happened to have climbed the mountain himself fifty years previously. However, the fellow “had got for his pains nothing except fatigue and regret, and clothes and body torn by the rocks and briars. No one, so far as he or his companions knew, had ever tried the ascent before or after him.” Petrarch's brother headed for the summit by the most direct, and therefore hardest, route; while the poet, being wilier or lazier, kept trying other paths in the hope of finding an easier way. Each time the trail proved false, and such shameful halfheartedness brought Ovid to the climber's mind. “To wish is little: we must long with the utmost eagerness to gain our end.” For Petrarch, the excursion up the Ventoux turned out to be a metaphor of the spiritual journey: it is uphill all the way, and there are no shortcuts.

But bikers, like hikers, are always looking for shortcuts. Next to the Simpson display window in Llandrindod Wells, I saw a publicity photograph of Mrs. Billie Dovey, a prewar cycling belle pro moted as “the Rudge Whitworth ‘Keep Fit Girl.’” This smiling, bespectacled icon pedals towards us in sepia innocence, an advertisement for comradely physical improvement,

mens sana in corpore sano.

But, as in most sports, the higher and the more professional you go, the less Corinthian it becomes. Various factors led to Simpson's death on 13 July 1967: the heat, the mountain, the lack of support (he was riding with a weak national team), the pressure on a rider approaching thirty to win the Tour before his time passed. But the prime cause of Simpson's heart attack on Mont Ventoux was the use of amphetamines, which helped his body ignore sense, and made his last words a dying plea to be put back on his bike. Traces of amphetamines were found in Simpson's body and among his kit. Speed kills, the moralists asserted. But Simpson's case was hardly egregious. Amphetamines—famously used to keep bomber crews alert on long missions—were widely consumed by cyclists in the postwar years. Their explosive effect caused them to be nicknamed

la bomba

in Italian,

la bombe

in French, and the somewhat more sinister

atoom

in Dutch. In the late Fifties, the legendary Italian rider Fausto Coppi was asked on French radio if all riders took

la bomba.

“Yes,” he replied, “and those who claim the opposite aren't worth talking to about cycling.” “So did you take

la bomba?”

the interviewer continued. “Yes, whenever it was necessary.” “And when was it necessary?” “Practically all the time.” The five-time Tour winner Jacques Anquetil told the French sports daily

L'Equipe

in the year Simpson died, “You'd have to be an imbecile or a hypocrite to imagine that a professional cyclist who rides 235 days a year can hold himself together without stimulants.”

Benjo Maso, the Dutch sociologist and historian of cycling, enlightened and depressed me about the prehistory of drug use. In the early days, this meant mainly strychnine, cocaine, and morphine,

*

though there were also folksier pick-me-ups, like bull's blood and the crushed testicles of wild animals. An Englishman named Linton died from his exertions in the Bordeaux-Paris race of 1896; his death was generally attributed to the use of morphine. In the 1920s, riders fuelled themselves with “incredible amounts of booze.” Maso cited another Bordeaux-Paris race (the event called for herculean stamina, being run in a single stretch, right through the night) in which one team's allowance per man was a bottle of eau-de-vie, some port, some white wine, and some champagne. These alcoholic habits continued; there are photos of Tour de France riders refuelling in bars and cafés. At Bédoin, where the Ventoux climb begins, Simpson supposedly complicated his body by stopping off with other riders for a drink; rumour has served him with a whisky and a pastis. This may sound foolishly self-defeating now, but at the time Tour regulations permitted the riders' support staff to give them liquid only at certain intervals; moreover, there was a general belief in the

peloton

(the main bunch of riders) that alcohol taken during the course of an event did you no harm, since it was quickly sweated out. Athletes and alcohol: when Captain Webb swam the English Channel in 1875, he washed his breakfast down that day with claret, and sustained himself on the way to Calais with brandy and “strong old ale.” So has it always been going on, I asked Maso. “Well, they had breath tests for alcohol in the ancient Olympic games,” he replied.

This all seems less shocking when you look at the terrain and remember that the riders have to cover 3,630 kilometres in three weeks, with only two rest days. The Tour de France is easily the most punishing endurance event in the athletic world. A triathlon, by comparison, is a fun-run. (Armstrong was a triathlete before becoming a professional cyclist.) The British rider David Millar, a Tour débutant this year, summed up a day that for him had consisted of eight and a half hours in the saddle, followed by a two-hour traffic jam to get to a hotel where the restaurant had closed and he was unable even to get a massage: “Sado-masochism.” If driving down the Ventoux to Bédoin leaves you croaking for a whisky, you'd certainly need one if asked to cycle up it; even the Rudge Whitworth Keep Fit Girl might take a snifter. The nearest equivalent to her on the Tour de France was perhaps Gino Bartali, Coppi's great rival, who won the race twice, in 1938 and 1948. “I didn't need drugs,” he once said. “Faith in the Madonna kept me from feeling fatigue and pain.” But such Petrarchianism was rare; for many riders miracles existed only in capsule form. With amphetamines, there was even a certain rough justice: they helped get you up the mountain one day, but exacted their price the next. Both Coppi and Simpson were known for their

défaillances,

their days of weakness; though doubtless climbing Ventoux without chemical help would leave you pretty tired the next day anyway.

*

Such speedy, boozy days now seem almost innocent; and they were innocent in that Coppi's use of

la bomba

didn't contravene the cycling regulations of the day—amphetamines were declared illegal only in the mid-Sixties. The quantum leap came when drugs designed to stimulate were replaced—or, in real terms, joined— by drugs designed to fortify, notably growth hormones and EPO (erythropoietin). Instead of helping suppress pain and giving you the illusion that you were stronger than you actually were, the new drugs really did make you stronger. In addition, Maso explained, “There are no bad days, as with amphetamines.” From the early Nineties, EPO became the drug of choice among many professional cyclists. Its function is to raise the red-blood-cell count, which sends more oxygen to the tissues, thus increasing your endurance and powers of recovery. If there are two riders of equal ability, the one taking EPO will always beat the one who remains clean; it really is as simple as that. And until this year, the presence of EPO was not detectable; only its suspicious consequences were.