Something to Declare: Essays on France and French Culture (10 page)

Read Something to Declare: Essays on France and French Culture Online

Authors: Julian Barnes

Could it be that Elizabeth David was too good a writer to be a food writer? Or is this just special pleading by one who needs constant textual hand-holding? Probably. E.D. cites a recipe of the French gastrotechnologist Edouard de Pomiane as “the best kind of cookery writing,” by which she means something that is “courageous, courteous, adult.” Further, “It is creative in the true sense of that ill-used word, creative because it invites the reader to use his own critical and inventive faculties, sends him out to make discoveries, form his own opinions, observe things for himself, instead of slavishly accepting what the books tell him.” E.D. herself could not be better described than as “courageous, courteous, adult.” Perhaps her ellipses are in fact sly encouragements to adulthood. Perhaps my frenzied use of the potato masher was, in its small and shameful way, creative?

Elizabeth David stood for: excellence of ingredients, simplicity of preparation, respect for tradition and for region. She stood against: fuss, overdecoration, pretentiousness; “heaps of vegetables” and “food tormented into irrelevant shapes”: the castellated radish, the limply supportive lettuce leaf, the worm-cast of potato salad. She was wary of three-star restaurants and ambivalent about

nouvelle cuisine.

She sang of the Mediterranean but was also learned about British food. Her approach is always unsnobbish, even if snobberies attach to some of her followers. She could be scholarly about the history of sardine canning, and equally precise about “the sound of air gruesomely whistling through sheeps' lungs frying in oil.” She described the state of the British bread industry with a fury worthy of Evelyn Waugh, but, instead of Wavianly bemoaning the equivalent of the Cripps-Attlee terror and retreating into the brandy balloon, she told people how to go about making proper bread themselves, and so helped kick-start the British bread revival.

E.D. was a liberator; perhaps it is not absurd to compare her effect on a certain sector of tired, hungry, impoverished Fifties Britain with Kinsey's effect on America. Perhaps she knew even more than he: that pine nuts, basil, and garlic are more certain providers of pleasure than unreliable human flesh. She became famous, revered and fetishized within her own culture, to the point where one instinctively searches for the

but.

Asking around among foodies, I turned up a few small buts, or semi-buts: that all food writing is evolutionary, not revolutionary; that other, forgotten figures were aware of the South at the same time; that her influence is narrower than supporters claim, or hope; that the over-all effect of her work has been to persuade Britain away from its authentic culinary roots, resulting in the geographical anomaly of the Birmingham housewife proudly serving up a Provençal dinner. “To put it crudely,” an ex-restaurant critic suggested to me, “where are the recipes for Brussels sprouts?” Where, indeed; and that is part of the point. In

French Provincial Cooking

Elizabeth David quoted Ford Madox Ford, fellow-Mediterraneanist and enthusiastic home cook, on one of the prime virtues of Provence: “There there is no more any evil, for there the apple will not flourish and the Brussels sprout will not grow at all.”

*

These buts and semi-buts would have been irrelevant to those who assembled in February of 1994 for the sale of E.D.'s kitchen remnants. I went along one viewing afternoon, intending to return for the sale, but was unnerved by the atmosphere, a smellable mix of melancholy, hysteria, and acquisitiveness. The melancholy came not so much from the hovering fact of Mrs. David's death two years previously as from the pathetic nature of most items: chipped jugs, two-legged colanders, battered sieves, stained cookbooks, bashed-up wooden spoons. Apart from a Welsh dresser and the large table at which E.D. had both cooked and written (bought by Prue Leith for eleven hundred pounds), it was—objectively— junk. As one of her nephews tactlessly admitted, “The best has been creamed off. It's gone to family and friends. These are the dregs.” But these resonant dregs had been touched by the radioactive hand of Mrs. David, and the auction raised £49,000, three times the Phillips estimate. Francis Wheen, the biographer of Karl Marx, spent £220 of his capital on three cheesegraters, two paperbacks, and a nutmeg grater—the last item still containing a talis-manically half-used nutmeg.

In 1976, when Elizabeth David collected her O.B.E., the Queen asked her what she did. “Write cookery books, Ma'am.” To which the Queen responded, “How useful.” It isn't known if the monarch then rushed—or sent—out for potted basil, extra-virgin olive oil, live yeast, and the right sort of bread crock. But for once she spoke for her nation. E.D. was, and after her death continues to be, very useful. It isn't always the correct accolade for a prose writer, but on this occasion it is.

*

She didn't. Two of the things she always refused to stock at the Elizabeth David shop were the wall-mounted knife-sharpener and the garlic press.

*

Sprouts were an

idée fixe

for Ford: “Any alienist will tell you that the first thing he does with a homicidal maniac after he gets him into an asylum is to deliver, with immense purges, his stomach from bull-beef and Brussels Sprouts.”

(5)

Tour de France 1907

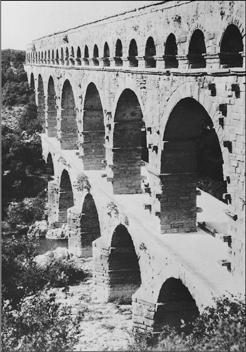

The Pont du Gard: “a little stupid,” according to Henry James

The first

Michelin Guide to France

—limp-bound, pocket-sized, and, of course, red—came out in 1900. “The appearance of this work,” its foreword pomped, “coincides with that of the new century, and the one will last as long as the other. The art of motoring has just been born; it will develop with each year, and the tyre will develop with it, since the tyre is the essential organ without which the car cannot travel.” The years between 1900 and 1914 were a blessed age for motorists (and, no doubt, for tyre-developers): a time at which—for those who could afford it—technology seemed to have advanced the possibilities of pleasure with no apparent drawback. “In those days,” Ford Madox Ford recalled, “the automobile was a rapturous novelty, and when we had any buckshee money at all it went on hiring cars.” Henry James declared that “the motor is a magical marvel,” and there can have been few more attractive countries in which to turn loose its magic than what he called “this large smooth old France.”

Edith Wharton—like Ford, like Conrad, like Kipling—took to motoring with a passion. The rapturous novelty was modern yet also cleverly historical: for Wharton it restored “the romance of travel,” offering the “recovered pleasures” experienced by “our posting grandparents.” What had destroyed these pleasures were the iron routes and timetables of the railway; now the motorist was freed from such dependency, and could enjoy a sharp sense of increased individual liberty. As the

Baedeker Guide to Southern France

of 1907—the year in which she undertook the second of her three “motor-flights”—candidly put it: “Motoring enjoys an enor mous vogue in France, principally owing to the absence of police-restrictions and to the excellent roads.” From the opposite end of the century, when Europe's autoroutes are clogged with freight, and individual vehicular liberty often consists of no more than the right to be by yourself in a traffic jam, it's easy to imagine, and to envy vividly, our own motoring grandparents.

Edith Wharton was quite unconcerned about all mechanical aspects of the magical marvel; but she grasped clearly what Percy Lubbock called “the opportunity of its power.” As he put it, she “remained an example to all for the intelligence with which she worked the capacity of her slave. It played an honourable, never obtrusive or assertive part in innumerable excursions”—in England, France, Italy, and the States. It also brought unexpected creative benefits. In her autobiography

A Backward Glance,

Wharton describes her early American motoring adventures, and how “one would set out on a ten-mile run with more apprehension than would now attend a journey across Africa.” Gradually, she began to make longer and longer sorties into the remote blue hills of Massachusetts and New Hampshire, “discovering derelict villages with Georgian churches and balustraded house-fronts, exploring slumbrous mountain valleys, and coming back, weary but laden with a new harvest of beauty.” Laden sometimes with more than this: for it was the suddenly possible exploration of these “villages still bedrowsed in a decaying rural existence,” filled with “sad slow-speaking people,” that provoked her bleak masterpiece

Ethan Frome,

as well as its warmer pendant

Summer.

In this American phase Edith Wharton and her husband Teddy got through numerous motors: “selling, buying and exchanging went on continually, though without appreciably better results.” The three journeys she described in

A Motor-Flight Through France

were all undertaken in the same secondhand 15hp Panhard bought by Teddy in London. Literary—and perhaps automobilistic— decorum prevented her giving us details of punctures, oil-changes, and breakdowns; social decorum from giving us details of fellow passengers. Also textually suppressed was the level of domestic support on these motor-flights: half a dozen servants went ahead by train or van and prepared for the subsequent arrival of the principals. Writing from the Grand Hotel in Pau while Teddy Wharton was laid up with bronchitis, Henry James alluded to this aspect of their travels in a typical parenthetical curlicue: “My hosts are full of amenity, sympathy, appreciation, etc., (as well as of wondrous other servanted and avant-courier'd arts of travel).”

The first flight, a two-week run from Boulogne down to Clermont-Ferrand and back to Paris, took place in May 1906 with Edith's brother Harry Jones for company; the second, a big circle of the southwest, the Pyrenees, and the Rhône Valley, occupied just over three weeks of March–April 1907, with Henry James as fellow passenger; for the third, a quick dash into Picardy over the Whitsun weekend in 1907, Edith and Teddy were unaccompanied. Their regular chauffeur was Charles Cook, a man of “native Yankee saneness and intelligence,” according to James. Wharton wrote up the flights for the

Atlantic Monthly,

and published them in book form in 1908.

It would be a misapprehension to assume that James—elderly, distinguished, yet not rich—was the guest of the younger and much richer Whartons. In fact, he paid his own way, and the hotels de luxe which his hosts automatically patronized put him to financial strain. As he admitted in another letter from Pau, he was living “an expensive fairy-tale,” learning once again how it was always “one's rich friends who cost one.” He realized with some apprehension that by the end of the trip there would be six servants, plus chauffeur Cook, to tip. James evidently forbore to mention such embarrassments to the Whartons, although Edith would certainly have had a general awareness of his financially subservient state. Percy Lubbock tells a story of the two writers taking a drive in Edith Wharton's latest brand-new motor—bought, she just happens to mention, with the proceeds of her last novel. “With the proceeds of

my

last novel,” James replies meditatively, “I pur chased a small go-cart, or hand-barrow, on which my guests' luggage is wheeled from the station to my house. With the proceeds of my next novel I shall have it painted.”

The early motorist had to be an adventurous stoic. The 1900

Michelin Guide,

alongside various remedies for mechanical ills, lists its special formula for “driver's eye-lotion” (450g infusion of coca leaves, 25g cherry-laurel water, 15g biborate of soda). Wharton's very first motoring experience—a thrilling hundred-mile round trip from Rome to the Villa Caparola in 1903—left her with two afflictions: acute motor-fever and acute laryngitis, the latter keeping her in bed for several days. On subsequent expeditions she was obliged, even in the hottest weather, to take the precaution of being “swaddled in a stifling hood with a mica window, till some benefactor of the race invented the windscreen and made motoring an unmixed joy” The Wharton windscreen appears to have arrived between the first and second motor-flights. For the 1906 trip they went unscreened and were pursued by rain: “It has been a cold, dark dreary spring in Europe, owing to Vesuvius they say.” But we know that at some point before departure for the south Teddy Wharton personally made modifications to the car, closing in the body, installing interior electric light, and adding “every known accessorie and comfort.”

It was Henry James who proposed himself as companion on the second and longest of these motor-flights. When he heard about the previous year's trip—and in particular about the visit to George Sand's house at Nohant—he reacted with theatrical yet real jealousy He had, he wrote to Edith, “a strange telepathic intuition. A few days after you sloped off to France I said to myself suddenly: ‘They're on their way to Nohant, d—n them! They're going there—they

are

there!’” Such envy is understandable: during his younger days in Paris, James had met Flaubert, Gautier, and Maupassant, each of whom had described to him the Second Empire's most famous literary pilgrimage—then made by train and diligence—to visit

la mère Sand.

Now, writing from the Reform Club in November 1906, James begs Wharton to recount “Your adventure and impressions of Nohant—as to which I burn and yearn for fond particulars. Perhaps if you have the proper Vehicle of Passion—as I make no doubt—you will be going there once more—in which case

do

take me!” This request accounts for the only narrative duplication in

A Motor-Flight;

though on the second visit to Nohant James's presence helped gain them access to the interior of the house.