Something to Declare: Essays on France and French Culture (7 page)

Read Something to Declare: Essays on France and French Culture Online

Authors: Julian Barnes

Upstairs I listened to Brel satirically discussing his own death in “Tango Funèbre” and in “Le Moribond”:

Et je veux qu'on rie

Je veux qu'on danse

Je veux qu'on s'amuse comme des fous

Je veux qu'on rie

Je veux qu'on danse

Quand c'est qu'on me mettra dans mon trou

*

As for Brassens, the album that he brought out during my year in Rennes—

Georges Brassens IX

—began with an enormous departure for this established master of the two-, three-, or if you were very lucky four-minute ballad. “Supplique pour être enterré sur la plage de Sète” (“Petition to Be Buried on the Beach at Sète”) weighs in at a marathon seven minutes and eighteen seconds. It is a grand, lilting, jocular codicil to his earlier testamentary songs, and contains specific instruction for the disposal of his body. He wants it transported

“dans un sleeping du Paris-Mediterranée”

to the “minuscule” station at Sète (where the station-master would probably have the delicacy to give himself the day off), and thence to the beach for burial. The eternal

estivant

is to lie in the sun between sky and sea, spending his death on holiday. He hopes that girls will undress behind his tomb; perhaps one of them will even stretch out on the sand in the shadow of his cross—thus affording his spirit

“un petit bonheur posthume.”

And just as Brel in Altuona was to have Gauguin for company, at Sète Brassens would be close to Paul Valéry, delineator and occupant of

Le Cimetière marin.

The singer, a humble troubadour beside the great poet, would at least be able to congratulate himself that

“Mon cimetière soit plus marin que le sien”

(“My graveyard is nearer the sea than his”).

In the event, he didn't quite make the beach. Instead, on the first weekend of November 1981, he was added to the family vault in the Corniche cemetery: this despite complaining in the “Supplique” that the vault was already stuffed to bursting point and he didn't want to be reduced to shouting “Move along inside there please”—

“Place aux jeunes en quelque sorte.”

(The sea is barely visible from here, and his grave after all less

“marin” than

Valéry's.) The ending of his life contained the symmetry he desired and feared: born in Sète in 1921, the naturalized Parisian returned to die there sixty years later. In that shortened span he never travelled well himself, being allergic to aeroplanes and abroad; while his songs, with their compacted, allusive, slangy texts and spare music, have travelled less successfully than those of Brel. But he was France's greatest and wisest singer, and we should visit him— spending his death on holiday—in whatever way we can.

*

When Paul Valéry met the correct English poet W. E. Henley in 1896, he was shocked to find the Englishman expressed himself with much idiomatic and perfectly accented obscenity. It turned out that Henley had learnt French from Rimbaud and Verlaine.

*

“And if I were God / I don't think I'd be too proud / I know, you can only do what you can / But it's the way you do it that counts.”

*

A note on the social penetration of Brassens's work. Three decades and more later, Jacques Fouroux was preparing the French rugby team to face the New Zealanders in the ritual encounter between flair and structured method. The coach reminded his men that, “to quote Brassens,

le talent sans technique nest qu'une sale manie.”

*

“I want you to laugh / I want you to dance / I want you to have a bloody good time … when they put me into my hole.”

(3)

The Promises of Their

Ordination

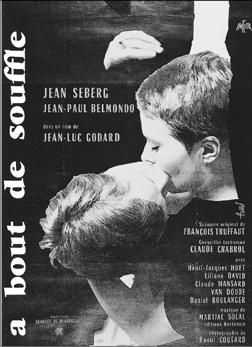

Jean Seberg kisses Jean-Paul Belmondo to advertise

A bout de souffle

Near the start of Truffaut's

Tirez sur le pianiste

there is a deft moment of authorial cheek. Charlie (Charles Aznavour) returns from the piano bar to his rented room and climbs wearily into bed, cuddling an ashtray the size of a salad bowl. Clarisse (Michèle Mercier), the jolly tart who lives next door, sidles in with an offer. Charlie says he lacks the money; she offers him credit; he declines. None the less she stays, undresses, climbs into bed beside him, and sits, her breasts fully visible, talking about a movie she's just seen. He interrupts her: “In the cinema, it's always like

this,”

—and he pulls the bedclothes up around her into a parody of the starlet-sitting-respectably-up-in-bed shot. It is lightly done, and fits the jokey, tumbling relationship between Charlie and Clarisse. Still, it has its echo.

In the cinema, it's always like this:

but it isn't like this in life, and from now on it won't be like this in the cinema either.

My movie education began in Paris during the early Sixties, when the

nouvelle vague

was still a surfer's paradise. Godard 's

A bout de souffle,

with a script by Truffaut, seemed the ultimate modern film: brave, nose-thumbing, hip, stylish, sexy, anti-authoritarian, above all true to the jagged inconsequentiality and moral vacuum of life as Godard and I (plus Truffaut and a few more initiates) perceived it to be. Like

Tirez sur le pianiste

it thrilled to loucheness and the rough touch of urban contemporaneity: “The Underpass in Modern French Film” is a thesis waiting to be written. If the theme of both films was Man on the Run, the technique was Camera on the Run: the lens probed and wandered, scuttled and hopped. Godard and Truffaut were exultantly picking apart the grammar of film and risking new combinations; together they were seeing afresh both life and the possibilities of art, in a joyful collaborative rivalry reminiscent of, well, Braque and Picasso perhaps.

Watching

A bout de souffle

again after a gap of more than twenty years, my first reaction was to lament the way things seem unquenchably novel when you are eighteen because of an unawareness of context and prehistory. In the present case: tone from American film noir, moral stance from

L'Etranger

(much watered), pretentiousness and fake

aperçus

from avant-garde café life. Today the shooting of the policeman in the opening minutes no longer seems to me a moment of liberating, audacious anarchy, but a calculated ploy by both anti-hero and director/writer (kill a cop to give your film a gallon of plot-gas). What still grips, however, is the panache of Godard's direction. Here is someone in immediate control of the medium, confident enough to try anything (how long can that sequence of Belmondo and Seberg not going to bed together possibly last? Well, about as long as the parallel sequence in

Tirez sur le pianiste

where Thérésa confesses her “vileness” with the impresario). The zest, the cockiness, the sheer ardour of filmmaking remain as infectious as ever, and almost cover up the melancholy truth: that

A bout de souffle

is a tremendous display of style balancing on a minimum of content. The closeness of Truf-faut and Godard at the time of these two films was deceptive.

A bout de souffle

still looks more accomplished than

Tirez sur le pianiste.

But Truffaut was just trying on the bell-bottoms; Godard was laying in a lifetime's supply.

The

nouvelle vague

was a revolt against

le cinéma de papa,

but it was less a matter of mass parricide than of selective culling. The wisest innovators know—or at least find out—that the history of art may appear linear and progressive but is in fact circular, cross-referential, and back-tracking. The practitioners of the

nouvelle vague

were immersed (some, like Truffaut, as critics) in what had preceded them. This was perhaps the only artistic revolution that began in a museum (the Cinémathèque), and in their films the revolutionaries acknowledged with many a wink and nod their favoured masters: thus in

La Nuit américaine

the film crew set off for a location shoot down the Rue Jean Vigo. Such hat-tipping was returned: Jean Renoir (Truffaut's French hero as opposed to his American hero, Hitchcock) slyly dedicated

My Life and Films

to “those film-makers who are known to the public as the ‘New Wave’ and whose preoccupations are also mine.” The

nouvelle vague

was denunciatory and iconoclastic in manner; but while knocking the heads off a few statues it none the less carried on building the cathedral. It developed and promoted the

auteur

theory, while also retrospectively applying it to American

cinéastes

like Howard Hawks; it loosened the financial garrotte with which film backer had long held film maker; it confirmed a move away from studio shooting to a sort of

plein-airisme;

and it turned its back on the established star system, while inevitably producing stars of its own, some of whom duly behaved with traditional megalomania.

By 1982 Truffaut could take a historial view of the

Cahiers du cinéma

row of the 1950s. He told the American critic Jim Paris that he still looked out for examples of

le cinéma de papa

when they came around again on television. He always hoped for a “pleasant surprise.” But the distinguished film maker of fifty found that his objections remained the same as those of the feisty young critic: “These relate mainly to the representation of love, the female characters, the anti-bourgeois

statements,

the absence of children and above all the falseness of the dialogue.” He concluded:

The revolt, to use a very grand word, of

Cahiers du cinéma

was more moral than aesthetic. What we were arguing for was an

equality

of observation on the part of the artist

vis-à-vis

his characters instead of a distribution of sympathy and antipathy which in most cases betrayed the servility of artists with regard to the stars of their films and, on the other hand, their demagoguery with regard to the public.

To each his own revolt: for Godard it was chiefly aesthetic and political, for Truffaut financial and moral. “Why don't you make political films?” the tiresome German fan demands of the film director Ferrand (played by Truffaut himself) in

La Nuit améri-caine.

“Why don't you make erotic films?” Ferrand doesn't reply; he is too busy getting on with the job. And in Truffaut's case, too, the main answer must come from a body of work whose character was settled early, and more by cinematic instinct than ideological decision. “A film-maker shows what his career will be in his first

150

feet of film,” Truffaut wrote of Jean Vigo. Apply this test to his own first feature,

Les Mistons,

and what sort of film maker do we discover? One attracted to the love story that ends badly, and with a singular empathy for the child on the nervous edge of adolescence; one with a taste for cinematic quotation, borrowed gags, and surprise cameo moments, plus a reliance on the literary device of voice-over narration; a storyteller imbued with charm, lyricism,

aigre-doux

humour, and a predilection for sunlit woodlands. (Is there a danger of sentimentality? Perhaps. But we might recall Alain-Fournier's reply to this charge: “Sentimentality is when it doesn't come off—when it does, you get a true expression of life's sorrow.”) And if we look behind the film, we discover an equally vital element:

Les Mistons

was largely financed by Truffaut's wife. This is a key lesson of the

nouvelle vague,

and one on which Truffaut and Godard could agree: that in an essentially collaborative medium, collaboration with the wrong money destroys individualism.

“When I was a child … I hated my family, I was bored by my family.” The young Truffaut dropped out of school at fourteen, and diversified into petty theft and minor vagabondage. When he stole a typewriter, his father committed him to a psychiatric “observation centre.” (A few years previously, Godard had stolen from Swiss Television, and been put in a mental hospital by his father.) Truffaut next joined the army, only to spend his time there in a constant state of near desertion. These experiences fed directly into the Antoine Doinel cycle of films, with the febrile, burning eyed Jean-Pierre Léaud as Truffaut's half-lost, half-damaged alter ego. This rich theme of fractured childhood and the search for a salvaging parent figure climaxes in Truffaut's painful and pessimistic masterpiece,

L'Enfant sauvage,

the tale of Victor, the Wild Boy of Aveyron, and Dr. Itard, his potential saviour. But while Truffaut's own story was that of a wild boy tamed and helped by a surrogate father (the film critic André Bazin), one finally consoled and fulfilled by learning to speak the language of film,

L'Enfant sauvage

is a bleak example of the story not working out. For all Itard's patience, inventiveness, and occasional exasperated toughness, small breakthroughs fail to lead to larger ones. Victor cannot finally be helped, the damage being too great for more than superficial remedy; he manages to pick up a few words and a few tricks, but fails to master language in such a way as to bring true communication and possible consolation.