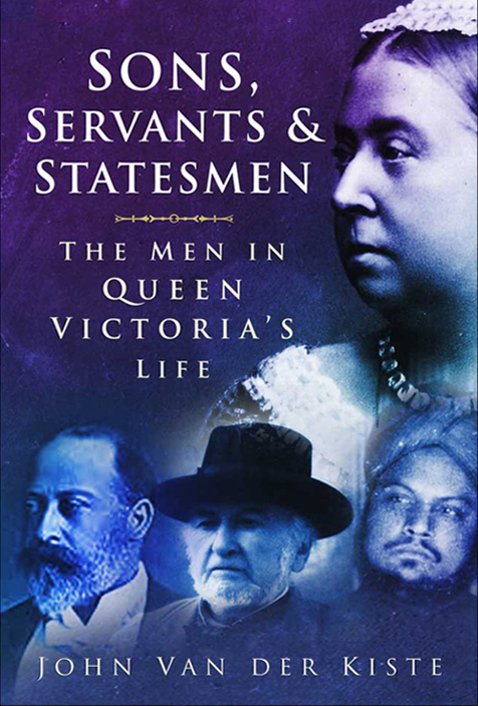

Sons, Servants and Statesmen

Read Sons, Servants and Statesmen Online

Authors: John Van der Kiste

Tags: #Sons, #Servants & Statesmen: The Men in Queen Victoria’s Life

ONS

,

S

ERVANTS

&

S

TATESMEN

S

ONS

,

S

ERVANTS

&

S

TATESMEN

HE

M

EN IN

Q

UEEN

V

ICTORIA’S

L

IFE

J

OHN

V

AN DER

K

ISTE

First published in 2006

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire,

GL

5 2

QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved ©

John Van der Kiste, 2006, 2011

The right of John Van der Kiste, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN

978 0 7524 7198 3

MOBI ISBN

978 0 7524 7197 6

Original typesetting by The History Press

I

wish to acknowledge the gracious permission of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II to reproduce material which is subject to copyright. All the other illustrations are from private collections.

Several people have assisted greatly in different ways during the writing of this book. Coryne and Colin Hall, Karen Roth, Katrina Warne, Sue and Mike Woolmans, Robin Piguet and Ian Shapiro have been their ever-supportive selves, always ready with information when needed. The staff at the National Archives and the Kensington Public Libraries have also assisted with access to primary sources and published information. As ever, my wife Kim and mother Kate have been a tower of strength, not least in reading the manuscript in draft form and making invaluable suggestions for improvement. Finally, my thanks go to my editors at Sutton Publishing, Jaqueline Mitchell and Anne Bennett, for helping to see the work through to publication.

F

rom her early days, Queen Victoria admitted to having ‘very violent feelings of affection’. Her Hanoverian forebears had generally been an emotional family, not afraid to give vent to their feelings in front of others. They had nothing of the stiff-upper-lip quality so often associated with the typical Englishman. At the same time, she clearly had a fondness for masculine company, not in any immoral or amoral sense, but rather because she felt more at ease with the male of the species than with women. One modern biographer has remarked with considerable insight that she was a man’s woman, and the men she liked best were ‘strong and imperturbable men who made her laugh, maybe with a touch of the rascal about them’. Her husband was the exception to the rule, but most of the others she liked fit the description well.

Her dealings with men throughout her life therefore make for an interesting study. How did Her Majesty Queen Victoria of Great Britain, at the height of her nation’s prestige and global preeminence deal and interact with her family, her most favoured servants and her prime ministers? How did a woman, the most renowned sovereign of her age yet at the same time a constitutional monarch who in practice wielded far less political power than her predecessors, reconcile the demands of matriarch and ruler?

Human beings are generally a mass of contradictions, and Queen Victoria was no exception. Sometimes she would complain that she could not defend her country as wholeheartedly as she could have done had she been a king. At the height of the Russo-Turkish war in 1877, she wrote that if only she was a man, she would ‘give those horrid Russians . . . such a beating’. At others, she would admit the limitations imposed on her by her gender. ‘We women are not

made

for governing,’ she had admitted in 1852, ‘and if we are good women, we must dislike these masculine occupations.’ One day she almost railed at being a woman in a position which by its nature demanded certain masculine qualities, while on another she passively accepted the limitations of femininity, as there was naturally no alternative.

The attitudes she took to the most important men in her life on political and personal levels, her relationships with them and the psychological factors inherent in these are worthy of examination in their own right, and this is what I have endeavoured to do in this book. Her initial admiration for, then detestation of and finally grudging respect towards Lord Palmerston, and her liking of and later passionate hatred of Gladstone are in their way just as fascinating as her controversial and much-debated relationship with John Brown and her ever-changing feelings towards her eldest son and heir, the Prince of Wales.

Father Figures

‘The daughter of a soldier’

K

ing George III and Queen Charlotte had seven sons who survived to maturity. The fourth is one of the least remembered. Had it not been for marriage late in life, and for the daughter born to him and his wife eight months before he died, Prince Edward Augustus, Duke of Kent, might have been all but forgotten. Yet, though she would say little about her father during her long life, Queen Victoria occasionally referred to herself with pride as the daughter of a soldier. Discussing the armed forces with her ministers in November 1893, she remarked that she ‘was brought up so to speak with the feeling for the Army – being a soldier’s daughter – and not caring about being on the sea I have always had a special feeling for the Army.’

1

Prince Edward Augustus was born at Buckingham House on 2 November 1767 and given his first name in memory of his uncle Edward, Duke of York, a dissolute young man who had died at the age of twenty-eight that same week. The circumstances of his birth, he would say self-pityingly, ‘were ominous of the life of gloom and struggle which awaited me’.

2

In 1799 he was raised to the peerage, becoming Duke of Kent and Strathearn and Earl of Dublin.

Brought up with his brothers and sisters mostly at Kew Palace, Edward’s early life was not so cheerless as he might have wished others to believe, notwithstanding the harsh regime and discipline at home to which he and his brothers were subjected as small boys. However, like his elder brothers he was quick to react against the frugality of his parents once he reached manhood, and soon found himself deep in debt, a state of affairs which would remain constant to the end of his days. According to one writer of a later generation, he considered that the Royal Mint existed solely for the benefit of royalty,

3

though he was not the only member of his family to do so. Wherever he was stationed on military service, be it North America, Gibraltar or Europe, he considered that as a king’s son he had to live in comfort and maintain a certain sense of style. Any house in which he lived, and the gardens which surrounded it, had to be refurbished to the highest standards, with no expense spared. The bills from builders, carpenters, glaziers and gardeners soon rapidly exceeded his parliamentary income and military pay.

In the Army he rose to the rank of field-marshal, but even by the standards of the day he was regarded as a merciless martinet. He thought nothing of sentencing a man to one hundred lashes for a basic offence like leaving a button undone. In 1802 he was appointed Governor of Gibraltar and considered he had been sent to restore order in what had become a rather undisciplined garrison. His conscientious efforts to do so, in particular to curb the drunkenness of the men, soon provoked mutiny, secretly encouraged if not instigated by the second-in-command, who was keen to get rid of him. Within a year he had been recalled to England.

Despite his reputation as a harsh disciplinarian, away from the parade ground some people found him one of the most likeable of the family. With the exception of the Prince Regent, he was probably the most intelligent of the brothers. The Duke of Wellington once said that he never knew any man with more natural eloquence in conversation than the Duke of Kent, ‘always choosing the best topics for each particular person, and expressing them in the happiest language’,

4

and the only one of the royal Dukes who could deliver a successful after-dinner speech. This favourable opinion was not shared by his siblings. The Prince of Wales, later Prince Regent and King George IV, so resented his air of righteous self-pity that he called him Simon Pure, and his sisters considered him so hypocritical that they named him Joseph Surface after a character in Sheridan’s

The School for Scandal

.

Austere where creature comforts were concerned, he rose early in the morning, ate and drank little, and abhorred drunkenness and gambling. He was a close friend of the pioneer socialist Robert Owen, and it has been suggested that the Duke of Kent could claim to be the first patron of socialism,

5

at least in the annals of British royalty. He took a keen interest in Owen’s workers’ co-operatives, and in improving education for the working classes, in order that they might be able to better themselves. No slavish adherent to the Church of England, he sometimes attended dissenting services, much to the irritation of Manners Sutton, Archbishop of Canterbury. He actively supported over fifty charities, including a ‘literary fund for distressed authors’ and the Westminster Infirmary.