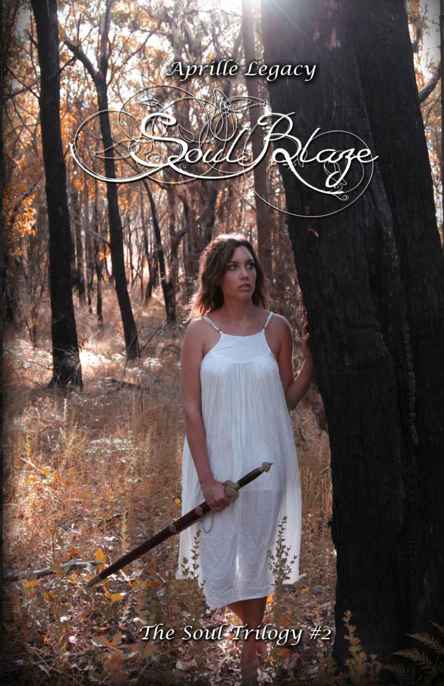

Soul Blaze

Authors: Aprille Legacy

The Soul Trilogy #2

Soul Blaze

First Edition 2014

Copyright © Aprille Legacy

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN 13: 9781490985879

ISBN: 1490985875

Front cover image by Brooklens Photography

Front cover model: Skye Foster

Cover design by E.J Duykers and R.A Dutton

T

his is a work offiction.Allcharacters are fictitious.

Any resemblance toanypersons livingor deceased is

coincidental.

Never once abandoned by your endless support.

There are few things more disturbing than waking up

to your hysterical mother.

I’d been awake for a little while, watching the sun pool

into my room. It was as I swung my legs out of bed to go

downstairs that I stepped on the one creaky floorboard,

and suddenly my room was invaded by a whirlwind of

tears and kisses.

embrace. “What’s wrong? Are you okay?”

“Am I okay?” she repeated tearfully, and I thought I

almost saw her smile. “Oh, Rose, my poor darling.”

She pulled me to her again, and as my face was pressed

into her shoulder, I was sure that we’d suffered a family

tragedy.

free of her grasp. “Who’s died?”

That wasn’t the right thing to say. She leant away from

me, heaving in air as she sobbed.

“Oh God,” I paled. “It’s Grandma, isn’t it? Grandma’s

heart?”

“It’s not Grandma!” she shouted through her tears. “It’s

you!”

“Me?” I’d never been more confused. “But I’m not dead”

“Yes, well I know that now,” she said, sitting on the

edge of my bed, tears still sliding down her cheeks. “But I

was starting to think-”

“Why would you think I was dead?”

“Because,” she took a deep breath, and my stomach

plummeted. “Because it’s been a year since anyone has

seen you.”

My breath caught in my chest. The birds in the tree

outside my window trilled and took flight. Finally I

managed to croak:

She nodded, and I suddenly noticed that she had my

left hand – along with the splint on my wrist - sandwiched

in hers.

managed to enunciate.

“We don’t know,” she said, looking into my eyes.

“When you were found on the river bank-”

“- the river bank?”

More desperate nods. I think she was trying to get

everything out as fast as she could.

“Yes. When they found you, your wrist was already

splinted. The hospital patched you up with a new one, but

they don’t know what happened to break your wrist.”

“Okay,” I found myself looking at the carpet on my

floor. There was a conspicuous amount of dust on it. I

suppose after a year Mum must’ve given up any hope of

me coming home. “Shouldn’t I be at the hospital or

something?”

“Doctor Fortescue checked you out when you were

brought back here. They’d like you to be brought in

though.”

“Sweetheart?”

I looked up into my mother’s eyes.

“Where were you?”

I opened my mouth to answer, and then realised there

was nothing there. No flashes, no snippets of conversation.

“I don’t know,” I said honestly, and her face fell. “I’m

sorry... there’s nothing there at all.”

“What is so awful that you can’t tell me?” her eyes

filled with tears again and I could see myself reflected in

them, my face older and thinner than last time I could

remember.

“If I could remember, I’d tell you,” I tried to reassure

her. “I’m hungry and I need a shower.”

“Alright,” she relented, but she was still upset enough

that my heart twisted to look at her. “But then we’re going

to the hospital.”

made her way to the door.

She stopped in the doorway and looked back at me.

“Then why have you lost a year of your memory?” she

asked slowly, and left before I could even begin to think of

a reply.

I stood in the shower for a long time, making sure my

splint didn’t get wet. I washed my hair with one hand

absent-mindedly, searching my memory for something,

anything to help me remember the events of the past year.

There was nothing though, and by the time my hair was

fruity fresh and steam was beginning to clog the small

bathroom, I was close to tears of frustration. I dried myself

awkwardly and dressed in jeans and my favourite green

hoodie.

As I reached for my beanie on my dresser, I noticed my

shirt was a little tight. Had it shrunk? No, certainly not. It

hadn’t been washed in a year – the musty dust smell

coming from it testified to that fact and made me wrinkle

my nose. Had my boobs gotten bigger? It wasn’t tighter in

my chest though, it was around my arms that it pinched.

I shrugged – with difficulty – and then wandered

downstairs into the kitchen to look for food. That one stair

still creaked, that shelf on the shoe stand by the door was

still broken. The rug in front of the front door was still

frayed on the left and there was still a big cobweb in the

corner of the window to the right of the door.

I still remembered the kitchen fire, but with difficulty,

as though I’d only dreamt it. I’d been cooking steak...

right? Or schnitzel?

My stomach growled at the thought of chicken

schnitzel slathered with gravy. There was no such luck to

be had in the bare pantry, and I had to settle with some

stale rice cakes and Vegemite (which defied age and time

by never going off).

I didn’t want to ask Mum why the cupboard was bare. I

didn’t want to hear that she’d lost her job, or that she’d

become anorexic.

“I usually just got take-away,” she said, appearing in the

archway between the kitchen and the living room. “Since

I had no one else to cook for.”

“So I’m the only reason you’re healthy then?” I asked,

attempting to make her smile.

One flickered and then died out.

“You were,” she said, and left the room, pulling her

phone out of her pocket.

I felt awful, and not just because the rice cake had been

older than I thought. She didn’t believe that I was telling

the truth.

In her defence, I used to lie a lot. When I was a kid, I

got my mouth rinsed out with soap a few times for being a

compulsive liar. Not the brightest one either, considering

it was only Mum and I living here, and I’d lie about things

like ‘who drank the last of the water in the jug and didn’t

fill it up?’ or ‘who put Glad-wrap on the toilet?’ That one

had gone horribly wrong when I’d forgotten than I’d put it

on there.

“Okay. Thanks, Dave,” I heard her say in the living

room. “I’ll bring her in now.” Her mobile beeped as she

cut off the call.

for the entrance hall. “I’m taking you down there now.”

I groaned, just quietly enough that she couldn’t hear. I

didn’t want to be poked and prodded at. But I’d do it in

the hope that I could reconcile my relationship with the

only person who had ever mattered in my life.

~

“Just roll your sleeve up for me, love,” Doctor Fortescue

said to me, holding a Velcro thing. “Just going to take your

blood pressure.”

The pad inflated and squeezed my arm. Doc Fortescue

watched the little dial for a second and then let it down

and made a note on his computer.

The only reason my blood pressure would be high

would be if my mother was standing in the corner of the

room, her arms crossed and nostrils flared like she did

when she was angry or stressed about something.

Doctor Fortescue noticed it too.

“Christina, could you just pop out for a second? You

seem to be elevating her stress levels.”

The nostrils flared again as I turned and faced her,

determinedly looking stressed.

You’d think she’d be happier about having me back.

My mother stalked out and closed the door behind her.

As soon as it latched, Fortescue turned back to me.

“So... went backpacking for a little bit, did we?” he

asked, his blue eyes serious.

“I swear I didn’t,” I replied, though I knew it’d be

hopeless. “I told you, I don’t remember anything about last

year.”

“Hm,” he tapped his chin with a pen, and I knew he

was trying to figure out if he believed me or not. “You

shouldn’t have put your mother through it, Rose.”

In this town I would always be that lying seven year old.

He did a few more tests and then proclaimed me to be

in perfect health. My wrist was also apparently healing

quickly from its mysterious injury.

small reminder. “And we could probably take it off then.”

I thanked him and left the small room. My mother was

leaning on the wall just outside, but before she could say

one word to me, one of the nurses was calling for her.

My saviour huffed and puffed her way down the

corridor to us. I thanked her over and over again in mind.

“It’s John Lowry again, he’s refusing to be treated by

anyone else but you and I told him you weren’t on today

but he wasn’t going to leave-”

“It’s alright,” my mother said, though I could see she

wanted to tell her co-worked to grow a spine. “I’ll see him

quickly.”

“Give me the keys and your wallet,” I said to Mum,

instinctively addressing her as I would’ve before all of this

happened. “I’ll pick up some groceries on the way home.

Text me when you need to be picked up.”

“Your phone disappeared with you,” she said darkly,

and I patted my pockets out of habit. “I’ll just call the

home phone.”

She tossed me her wallet and keys, which I caught

deftly to my surprise. I was generally clumsy, and with the

added fact that I could only use one hand, I should’ve

fumbled.

replaced by that mask of indifference.

It was a relief to step out into the car park by myself. I

took my time unlocking the car door, just allowing myself

some time to breathe for what felt like the first time in

months.

It took me a few attempts to get Mum’s car going. My

hands and feet incredibly uncoordinated, and I knew – by

the time I’d managed to pull out onto the main road – that

I certainly hadn’t been driving in my absent year.

I pulled into the shops, just as the sun disappeared

behind a wall of clouds rolling in from the mountains. The

sudden breeze made me glad I was wearing my hoodie.

I didn’t realise what effect my return would have on

the community until I stepped inside the sliding glass

doors. I didn’t notice it at first as I surveyed the aisles,

determined to restock our house with plenty of food. I

think I was reaching for a bag of apples when I saw the

first double-take. I recognised the woman; she was one of

my old teachers from primary school. As she stared at me,

apparently unashamed, I awkwardly gave her a small

wave and a half smile. I was confused by it until I saw

other women do the same.

Ar Cena is a small, country town. Everyone knows

everything about everyone. My disappearance would’ve

caused the biggest upheaval since I almost burnt the

kitchen down. My reappearance was starting a new wave

of gossip altogether. I could almost see it rising, new

rumours being born in front of me.

I waited for the confrontation. Someone had to do it.

They did. I was lined up for the check-outs when

someone tapped me, politely but firmly. I spun around to

face them almost reflexively.

“Welcome back to Ar Cena, Rose,” she started, her

steely blue eyes examining me. Mrs Johns used to be our

neighbour until a few years ago. She was the type of

woman who would occasionally bring over biscuits when

I was little but, yelled at me to turn my music down when

I was older. “You look… tanned.”

to look at myself in the mirror a lot.

“Indeed. Whereabouts did you travel?”

I realised then and there I needed to make up a lie. I

didn’t want to, but I couldn’t tell everyone that I didn’t

remember a year of my life.

much for me, you know?”

“I see,” she said coldly, and I knew that she

disapproved. “Are you going to be returning to school?”

She was making me think of things that I hadn’t had

time to consider. I decided that blasé was my best option

and shrugged.

Mum will make me.”

“Your education is very important, Rose. I’m sure your

mother would want you to finish school.”

I shrugged again. As I’d hoped, she let the conversation

end.

I paid for my groceries and hauled them out to the car.

I tried not the let Mrs Johns get to me, but I found myself

considering what she’d suggested as I drove home. Mum

would want me to finish school. I didn’t know if I was so

keen on the idea, but I just couldn’t wrap my head around

the idea of going to work full time at the tender age of

eighteen.

year, I would’ve turned nineteen.

Still, I thought as I turned into the driveway, maybe

going back to school isn’t such a bad idea.

I unpacked the bags into the bare pantry and fridge,

finishing just as the home phone rang; Mum had finished

with Mr Lowry and needed to be picked up.

The drive there and back was suffered in silence. Apart

from booting me out of the driver’s seat, it was almost like

I’d never come back in the first place.

pulled in. “You need to re-register it, too.”

I just nodded and climbed out. Mum started cooking

schnitzels (I quickly determined that I was no longer

allowed near the stove), whilst I climbed the stairs to my

room. I tugged the vacuum cleaner from its closet and set

about cleaning the dust from every surface.

sky streaked with pink and gold.

T

he sunwas setting, turningthe leaves onthe trees

brilliant hues oforange andgold. It madeit looklike the

forest was onfire, and itwas absolutely spectacular.

I stomped on the vacuum cleaner to turn it off. I

massaged my suddenly aching head as my hands began to

shake.