Star Wars on Trial (25 page)

Read Star Wars on Trial Online

Authors: David Brin,Matthew Woodring Stover,Keith R. A. Decandido,Tanya Huff,Kristine Kathryn Rusch

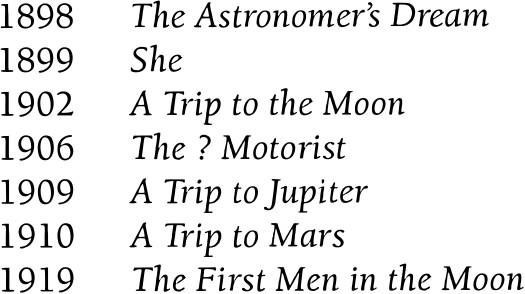

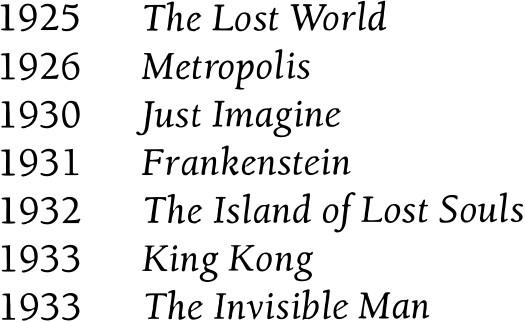

I think Fred Pohl said several times that Star Trek is really good science fiction for about 1920. And I think that's the trouble really The sophistication that you get in the best literary SF is far in advance of what you get on the average in media SE There are obviously exceptions, but on the whole, especially the stuff that's in the public's face-Star Trek, Star Wars-what the critics know about-it is just so far behind, the use of ideas and so forth. I think that's the trouble. We're all judged by that label, especially given the preponderance in the bookshops of media tie-in books and epic fantasy, and then science fiction and hard SF especially is just a tiny corner. It's difficult for them to get through the prejudice.

Getting through the prejudice. Which is a shame, because as many doors as Star Wars has opened in terms of special effects and imagination (and it has opened quite a few), it has also ushered in an era in which science fiction is seen as childish escapism and "serious" science fiction films have been extremely hard to produce. Like James Bond movies having to up the ante every time, no science fiction film could be made today on anything approaching a large budget without a prerequisite number of explosions, vehicle (car or spaceship) chases and fights, whether lightsaber duels or Matrixstyle kung fu. And while this has made for some wonderful popcorn cinema, I can't help but wonder what we are missing out on. Imagine for just a moment, if you will, the resulting films we might have been given had Stanley Kubrick's 2001 emerged as the benchmark against which Hollywood had set itself these past decades. If that cinematic masterpiece, and not Lucas's space opera, had inspired a sea of films with Oscar-caliber scripts and Oscar-caliber performances in the science fiction genre. What kind of a filmic landscape would we have had then? Like the number of licks it takes to get to the center of a Tootsie Pop, the world will never know.

The problem we face is that the general perception of our genre as overrun with Star Trek and Star Wars fans, and providing material only on a level with their tastes, may be a factor in keeping a larger populace from checking it out. How many of us, working professionals in this business, when asked what we do, inevitably have to endure quips about one or both of these two franchises? Wouldn't it be nice, just once, when explaining, "I work in science fiction," to have someone say, "Ah, yes, science fiction. That Samuel R. Delaney is a modern-day James Joyce, isn't he?" or "Did you know that Kurt Vonnegut's Kilgore Trout was named for Theodore Sturgeon?" Or, "You guys really have a handle on explaining to the rest of it where the whole world is heading. Thanks!" But alas, too often, it's all jokes about Spock ears and lightsabers and why don't you ever try writing a "proper book"!

Now, lest you think this is all just a bunch of sour grapes, there are some very practical, economic reasons why media tie-ins and novelizations are bad for business too.

THE BUSINESS OF WRITING

"They're bad because they've killed the midlist," explains Mike Resnick, a seasoned professional who knows more about the business of writing than just about any other writer I know.

Essentially the argument is this: writers as different and as idiosyncratic as Harry Turtledove, Gene Wolfe and I were all allowed to build our advances and audiences over a period of more than a decade. But today, with the midlist totally taken over by media books, there seem to be almost no novels in the $12,500 to $45,000 range. Instead of building from $5K to $9K to $14K to $20K and so on, now you go from $6K to $40K-an enormous leap of faith that most publishers are unwilling to make-or you stay at $6K. Why take a chance that you'll earn a $27K advance when they know a Trek book or a Wookiee book will earn out with no effort on the publisher's part?

Why indeed? This has led to our current situation, a shrinking of the midlist where publishers burn through promising new authors faster than Fox turns over new television shows, and scores of deserving talent are being discarded where an earlier age would have allowed their works to grow and take root. Do not believe otherwise. This is a very real problem, resulting in a sea of broken careers, and the genre is the poorer for it.

Nor are the works of which we're being deprived the only way in which the quality of the science fiction genre is being affected. Novelizations and tie-ins have another crime to answer for, as Resnick explains, "They're bad because they teach writers bad habits. Eight hundred years of literary evolution says that the protagonist must grow and change from his experiences-but novelizations of TV series require the same familiar character not to change. And they teach writers to be lazy-why describe how a process works when you can simply say, `They stepped into the Transporter beam,' and ten million kids know what it means?"

Look, you say, I work long hours, life is tough enough, and when I come home, I want something light and fun. What does it matter if I want some turn-your-brain-off entertainment anyhow? Or, in other words ...

WHY IS BAD WRITING BAD, ANYWAY?

First of all, let's define what we mean by good writing first, shall we? I don't think we can come up with a better definition of good literature than that supplied by the inestimable Gene Wolfe, who said, "My definition of good literature is that which can be read by an educated reader, and reread with increased pleasure." Or, as Samuel R. Delaney put it in an interview with Adam Roberts (Argosy magazine, January/February 2004), his writing is not generally intended for readers "who are not terribly interested in getting any other pleasure from a book except the one they open the first page expecting."

By contrast, when you read a novelization, not only are you getting exactly what you are expecting, you are almost certainly not getting a writer's best work. For starters, who would give away his best ideas, when he won't own the fruits of the labors? Writers save their best material for their own books, and put in the tie-ins that which they can bear to give away.

I've said it before and I'll say it again: science fiction is the genre that looks at the implications of technology on society, which, in this age of exponential technological growth, makes it the most relevant branch of literature going. We've lived through at least one singularity with the birth of the Internet, and the way this has transformed everyone's life in just a few short decades cannot be overlooked or downplayed. But this is only the start, and the close of the twenty-first century will look absolutely nothing like its inception. This hasn't ever been true in history before. The future has overtaken the present and things are only speeding up. The future exists first in imagination, then in will, then in reality, and the types of dreams we dream today will determine the world we and our children live in tomorrow. Our world is dreaming some dark dreams now. We need to dream better, as if our life depended on it. I suppose that it all comes back to meat loaf and filet mignon. If tie-in properties could be a gateway drug to the real stuff, wonderful. But if they pass in the mind of the majority for the real stuff, trouble. Because, my friends, the real stuff is important. The future is a very powerful force, if you just tap into it.

Lou Anders is an editor, author and journalist. He is the editorial director of Prometheus Books' science fiction imprint Pyr, as well as the anthologies Outside the Box (Wildside Press, 2001), Live Without a Net (Roc, 2003), Projections (MonkeyBrain, December 2004) and FutureShocks (Roc, July 2005). He served as the senior editor for Argosy Magazine's inaugural issues in 2003-04. In 2000 he served as the executive editor of Bookface.com, and before that he worked as the Los Angeles liaison for Titan Publishing Group. He is the author of The Making of Star Trek: First Contact (Titan Books, 1996), and has published over 500 articles in such magazines as Publishers Weekly, The Believer, Dreamwatch, Star Trek Monthly, Star Wars Monthly, Babylon 5 Magazine, Sci Fi Universe, Doctor Who Magazine, and Manga Max. His articles and stories have been translated into German, French and Greek, and have appeared online at Believermag.com, SFSite.com, RevolutionSFcom and InfinityPlus.co.uk.

THE COURTROOM

MATTHEW WOODRING STOVER: Okay, let's break this down. Your first objection is that (gasp!) Star Wars is fantasy. Say it ain't so! Uh, moving on-

Your second objection is that Star Wars is "seen as being indicative of the science fiction genre by the majority of moviegoers." In other words, it's been really, really successful. Uh, okay: guilty as charged.

Your third objection is that it "ushered in an era in which science fiction is seen as childish escapism and `serious' science fiction films have been extremely hard to produce." Which leads me to my first question: Are you seriously trying to tell this Court that there was an era, previous to Star Wars, in which science fiction was not seen, by the wider public, as childish escapism, and "serious" science fiction films were actually easy to produce? Are you trying to say that there is not more serious-or at least attempting to be serious-SF cinema now (e.g., Donnie Darho, Primer, Solaris, The Butterfly Effect, et al) than at any time in Hollywood history? I remind you that you are under oath.

LOU ANDERS: First of all, commercial success is not a barometer of quality, and you know that, or anyway you should. More power to Dan Brown for coming up with The Da Vinci Code, but the hackneyed prose he serves up wouldn't fly in the genre next door. And if the size of your audience is an indication of talent and literary merit, then Fear Factor is gripping, psychological drama. You will recall that I never faulted anyone his entertainment, simply bemoaned those who can't tell shit from Shakespeare and insist the one is the other.

Second, (with thanks to James Gunn):