Stars Between the Sun and Moon

Read Stars Between the Sun and Moon Online

Authors: Lucia Jang,Susan McClelland

Stars between the Sun and Moon

Stars

between

the

SuN

an

d

Moon

One Woman's Life in North Korea

and Escape to Freedom

Lucia Jang

and

Susan M

cC

LellanD

with an afterword by Stephan Haggard

Copyright © 2014 Lucia Jang and Susan McClelland

1 2 3 4 5 â 18 17 16 15 14

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777, [email protected].

Douglas and McIntyre (2013) Ltd.

P.O. Box 219, Madeira Park,

BC

,

V0N 2H0

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

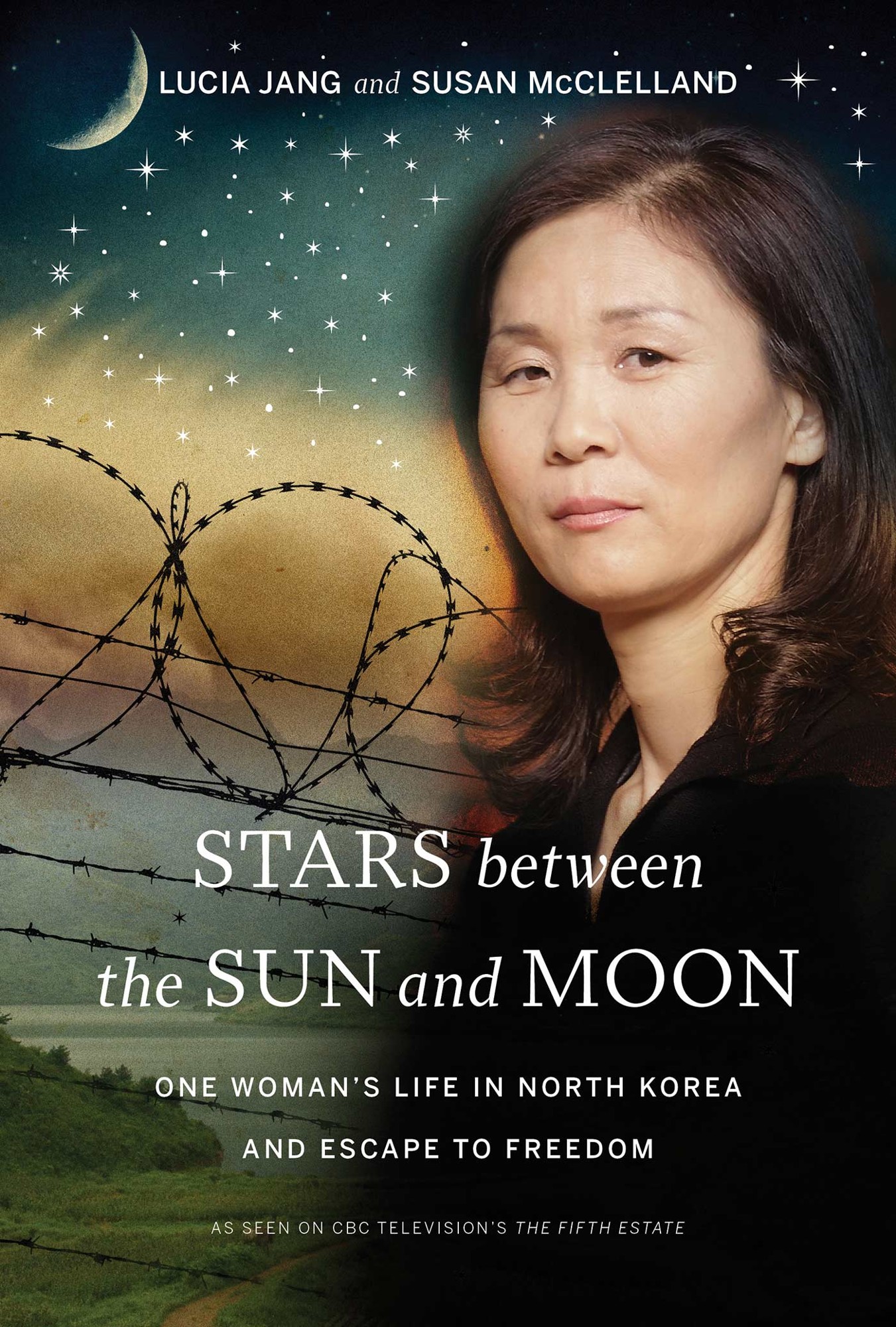

Jacket photograph by Tom Tkach

Edited by Barbara Pulling

Jacket design by Anna Comfort O'Keeffe & Carleton Wilson

Text design by Carleton Wilson

Printed and bound in Canada

Douglas and McIntyre (2013) Ltd. acknowledges financial support from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Cataloguing information available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN

978-1-77162-035-2 (cloth)

ISBN

978-1-77162-036-9 (ebook)

* * *

Some names, dates and place names in this account have been changed to protect those still living in North Koreaâalso known as Chosunâwho could possibly be imprisoned, tortured or killed for being connected to Lucia Jang. The author refers to herself as Sunhwa in the pages that follow; Lucia Jang is the name she chose for herself while living in Canada.

For my three sons, so that they may understand their history and their mother's love for them.

For Soohyun Nam, who sat between Susan McClelland and me nearly every Saturday morning for a year, to translate my story.

And finally, for the numerous, nameless North Koreans who attempted to escape to freedom and life, and perished on their journey before they could reach their destination, each with a story filled with as much heartache and pain as well as hope and love as my own.

âLucia Jang

Prologue

Dear Taebum,

I am looking at you now, as you sleep in the crib in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. My eyes are trained on your stomach as you inhale and exhale. I have never prayed before, but now I feel compelled to do so. I raise my hands the way I saw a South Korean man do in China, a man who wore a cross around his neck and whose home smelled of lavender incense and melting candle wax. I close my eyes, then stop before I can say a single word. You've made a strange sound. I fix the thin sheet around your weak and tired body, and then relax. Your face is calm again.

Taebum, there is so much I want to tell you. You are only a few months old, and I want you to grow wise so that these memories I have decided to place in a diary reach you. I want you to understand the forces that nearly destroyed us, and the force that I now know has kept us alive: love. You were never supposed to live. From the moment you were conceived, no one wanted you: your father, his family, China, the country where you were conceived or Chosun, the country where you were born. There was a forest of people trying to prevent your coming into this world. Even my mother, my

umma

, wanted me to be rid of you.

Back before you knew life, when I was in the prison camp and I knew the Party would force me to abort the child I was carrying, I began to sing a song. A light snow had begun to fall, but when I stood close to the window in my cell, I saw sun on a cloudless day. Through the chill that had consumed my body since I fled Chosun, I felt heat. I closed my eyes. “

Jjanghago haeddulnal Doraondanda

,” I sang softly. “A bright sunny day is to come back.”

I sang another song in my mind when I lifted you above my head in that plastic bag Abuji, my father, had made for you: the song of the Flower Girl, from the film I had loved so much in my youth. The bag protected you from the cold water and concealed you from the border guards who would have shot us both if they had seen. Only your face was visible, so you could breathe. I carried you across the Tumen River to China. I carried you in my arms here to Mongolia.

I have no idea what life will bring you, my son. We are about to be sent to South Korea, where we will be given an apartment and a new, safe existence. When you are older, I want you to read these words, even though they reveal many things about your mother. I will not hide the truth from you. In the midst of all that I endured I saw the sun, I felt its warmth. You will likely never set foot on the soil of your homeland. Nevertheless, I want you to understand the Chosun that is your soul.

Part One

Chapter One

My mother rarely

smiled. But when she did, her head would tilt to one side, her crimson-coloured lips parted slightly and her black pupils danced against the pearls of her eyes.

One time when this happened, we were sitting in our front yard, overlooking the crops of corn, beans and potatoes near our home in the small city of Yuseon.

“Daughter,” she whispered, pulling me into her arms. The smell of her body mixed with the chamomile scent from the

deulgukhwa

that had bloomed early and through which we had been walking. It was my fourth birthday, on the fifth day of the fifth month. As was customary, I had had a bowl of white rice for my morning meal to celebrate.

My mother stroked her belly, which was swollen. Her second child was due, she had told me, in the tenth month of this year.

“I am all yours for a little while longer, then you will have to share me,” she said. Her eyelashes reminded me of the wings of the tiger butterflies I saw in the mornings as they floated around the azaleas in the garden. “I want to tell you many things,” she continued. “I just don't know where to begin.”

“Umma, I want to know what âI love you' means.” I smiled, relaxing into her arms, feeling her hard stomach against my back. “I heard Abuji say this to you once.”

“Hmm. I will tell you. But before I begin, I beg you not to tell others,” she said quietly.

“I promise,” I said, my gaze falling on some sparrows nearby.

I can't remember all of what my mother said next, Taebum, since I was only a small child at the time. But she told me many stories from my childhood years later and as I grew older, and I will recount some of them for you here.

“My family, your

ancestors, come from a northern province in Chosun,” my mother began. “I grew up in a small cement house with my two sisters and three brothers. I was the eldest. I was the bravest. I was . . .Â

” her words trailed off for a moment. “The most outgoing. I danced my way to school. I sang songs not only about our great father and eternal president, Kim Il-sung, but about flowers and clouds, smiling children. Of course I sang songs from the Soviet Union, too. We all did.”

She smiled. “The darkness comes over the garden,” she sang for me in her perfect soprano voice. “Even the light has gone to sleep. The night in the suburbs that I love. The nights in the suburbs of Moscow.” I loved to sit with my mother and listen to her in this way.

“By the time I was twenty,” she continued, “I was a much sought after bride in the city of Hoeryong, where we lived. Men from all over Chosun came to Hoeryong to find their wives because Kim Il-sung's first wife, Lady Kim Jeong-suk, was from there.”

“Like Abuji!” I said eagerly. I knew my father had been born in Yuseon. “He went all the way there to find you!”

“Yes,” my mother hissed softly, like I imagined one of the tiny green snakes I'd seen in the hills might do. “But there was another man before your father. A military man. With a straighter back than mine and thick shoulders. He was so handsome in his uniform, but he left me with a sinking feeling. I knew we would always remain apart.”

“Umma, what is the matter?” I asked, seeing the sadness in my mother's face.

She ignored my question. “I was always called a pretty girl. I had many friends and I loved to sing, but I was never interested in boys. I sang and played the flute at the community centre. After one of my performances, a military man came backstage and said his friend wanted to meet me.

“The year was 1960. I met that military man, and he and his friend and I continued to meet every night following my performances for many months. The man told me I sang like a nightingale. After some time, I knew the day was approaching when he would ask his family if he could marry me. I also knew that before they could say yes, I would have to submit to them a full list of my relatives to show that I came from a patriotic family. A good man, like this man, could only marry a woman loyal to the regime. But I would never be that woman, Sunhwa. I had family members, an uncle and my grandfather, who had fled to the south by ship at the end of the war. My grandfather had helped some American army men who came to the north in search of communists. After the war, the regime started killing anyone who sympathized with the Americans, the enemy. My uncle and grandfather went south to save themselves.”

Having a relative leave Chosun for South Korea was the worst thing that could befall a family, she explained seeing my puzzled look.

“I learned this the day I decided to join the political Party and become a

dangwon

. I believed that would show the military man that I was dedicated to the regime and ready to marry him. That day, I put on my best white

jeogori

along with a black

chima

and

pyunlihwas

, and powdered my face. I planned to meet the military man that night after my performance and tell him what I had done.

“On my way out the door, my father stopped me. âAh, Hyesoon,' he moaned. âSit down.' He waved to the floor beside the table, where his morning rice was still steaming in a bowl. âWe need to talk.'

“He sat facing me, wringing his hands. His forehead was perspiring, I noticed, despite it being cold inside our home. I was impatient, my fingers tapping my knees.

âYou cannot become a Party member, a

dangwon

,' he said stiffly.

“In that moment, hearing his words, I felt as if I had been thrown a thousand

li

backwards.

“âYou have relatives in the south,' my father said, hanging his head. âThe Party won't let you join. Why do you think we live here, in a house with no heat, so far from the capital, sharing two rooms among all of us? It's all because your uncle and grandfather fled and are no longer here.'”

My mother sighed, looking off into the distance. “I understood then that only a man who also had a relative disloyal to the regime would take me as a wife. This military man would never be my husband. In this land, where snows blanket the earth for five months a year, choosing a husband for love was a gift that would never warm me.”

My mother stopped suddenly. She clasped my hand and pulled me to my feet. We stood watching my father walk up the road toward us in his dark cotton shirt, buttoned at the collar, and matching pants, the same outfit my mother and all our adult neighbours wore. His big black boots made his legs appear heavier than they really were. As he drew near, I could see that his cheeks were red from the wind. His coarse hair was tangled, as if a bird had used it for a nest.

“Remember, what I have told you is our secret,” my mother said as she brushed off grass stuck to my navy-blue cotton pants.

“I want to know the ending, Umma,” I begged.

“Later. Now we must go. Your grandmother is visiting. She may have brought some extra rice with her.”

“Changwoon, uh watnya?

â

Are

you here?” my grandmother called out, hearing the door open to our house.

I was stopped in the hallway by her cool stare as she and my grandfather approached. My father stepped up beside me.

“

Abuji, nae wassugguma

,” he said. “Father, I am here.” This is how we greeted people in Chosun.

I looked into my grandmother's well-lined face. Her lips were so tiny that whenever she wore lipstick, part of the paint bled onto her yellowing skin. “Can I have a candy?” I blurted.

My grandmother reached into her canvas bag, passed my mother a head of cabbage and some white rice, then held her empty hands out in front of her. “I don't have any,” she said.

My father's sister and her family lived nearby and now, as I peered around my grandmother and grandfather, I could see my cousin Heeok. Heeok had big brown eyes and a square body that made her look like a cement block. Like me, like all the children we knew, her hair was cut short by her mother, who trimmed it each month with heavy iron scissors.

Heeok's eyes grew large when she spotted me, and she made a show of chewing. She had a candy. I could see it when she opened her mouth.

“But what about her? What is she eating?” I asked my grandmother, defiantly pointing at Heeok.

“I only had one candy, and we visited her first,” my grandmother said. I looked pleadingly into Heeok's eyes as she stepped up beside me.

“Why do you always get things I don't?” I whispered.

She just smirked.

That afternoon, for our main meal of the day, we had a few extra spoonfuls of rice with our kimchi. I shovelled the food into my mouth, not stopping until my bowl was empty. I knew my behaviour was not polite and my father might hit me with the broom as later punishment for being rude to visitors. But I was starving. My stomach grumbled even in its sleep. Often, on the day my mother brought home our sparse government rations of white rice, mixed brown rice and other grains, sugar, noodles, and vegetables, I would sit on the floor and devour the noodles uncooked. My mother would squint her eyes, pucker up her lips and shake her head, meaning I was in trouble. She assumed that expression now.

When we were finished our meal, my grandmother announced that her youngest daughter, my father's sister, Youngrahn, would be arriving at our home the next day. “She will stay for a few months, to help you until the baby is born,” my grandmother told my mother sternly.

My mother's shoulders slumped, and her eyelids drooped. “I am honoured that Youngrahn will stay here,” she replied. It was the polite response, but I knew she was not happy. Even at my young age I has seen on earlier visits Youngrahn was spoiled and demanding.

Youngrahn breezed into

our house the next morning. She threw her coat on the floor in the room where my parents and I slept on cotton mats. “When I start university in a few months, I will get lots of food. The government knows I will need more food then to help me think,” she boasted to my mother and me. “Speaking of food, I'm hungry now.”

My mother hung my aunt's coat on a hook on the wall, then headed outside. I heard the creak of the wooden lid that covered the hole in the ground where we stored goat's milk and vegetables. When my mother returned, she began preparing some porridge.

My aunt dug a small mirror from her black leather purse and started to apply cream and pink powder to her face.

“Can I do that too?” I asked, placing one of my hands on her shoulder. She flinched and pushed me away.

“No,” she snapped. “This is for grown-ups. But I'll tell you a secret,” she said, lowering her voice so my mother wouldn't hear. “Your mother was the most beautiful woman anyone had ever seen when she was young. You might be beautiful too, when you get older.”

My body warmed at the thought.

“I'm going out to the movies tonight,” my aunt continued. “Maybe I'll meet my future husband there.” Her voice grew harsh again. “But no matter how beautiful you become, you will only be eligible for the men women like me reject.”

I turned away, my face hot, my palms perspiring, as my mother placed bowls of porridge in front of us.

My mother ate slowly. I followed my auntie's lead and cleared my bowl in a few spoonfuls. My stomach wanted more. I glanced pleadingly at my mother, trying to imagine what she had looked like when she was younger, her face round and soft, her eyebrows perfectly arched. I lifted my spoon and placed it in my mother's bowl.

“You naughty child,” my auntie snapped, grabbing my hand and tossing it roughly to the side. “Little one has a gigantic stomach! You are only allowed three hundred grams of food a day. You eat so much. You are a

pig

!”

“It's fine,” my mother said calmly, pushing her half-empty bowl toward me.

That afternoon, my

mother and I left my auntie alone in the house to nap. We headed to the hills, looking for cabbage or potatoes left behind on the farms following last year's harvest.

“Umma,” I said, when we sat down to nibble on some weeds, which on that day were all that we could find. “Can you finish your story? What happened when you told the military man about your uncle and grandfather?”

She sighed. “I didn't tell him at first. He asked me to marry him, and I agreed. I don't know what got into me. I was living in some dream. When he finally announced that his family needed the names of all my relatives, I stopped performing. When he came in search of me, I refused to meet him ever again.”

“Did you ever see him again, Umma?”

“I did,” she said, twirling a strand of hair in her long fingers. “It was after I had moved here with your father. I was walking you in the pram, with your grandmother and auntie. We bumped into the military man on the sidewalk. I was so shocked, I let go of the pram and ran away in a panic.

“When he caught up to me, he was crying. âWhy did you leave me?' he sobbed.

“âBecause I have an uncle and grandfather who defected to the south,' I told him, looking around first to make sure your father's mother and sister were nowhere in sight. As you know, it's not right for a married woman ever to speak alone to an unrelated man.

“âI don't care about that,' he said, his eyes locked on my own. âIf only you had told me.'

“I didn't know what to say. All my breath had left me. âYou are in the military,' I eventually said. âHow could you hold such a position and be married to me?'

“âI would have left the military to be with you,' he replied. âI know you have a child now but run away with me. Both of you.'”

My mother turned to face me. “I thought of you, Sunhwa. I thought of the moment when I first felt you stir inside me. I thought of your tiny fingers and how they curled around my own when I held you at night as we slept side by side. I thought of your soft hair and sweet, sticky smell. Then I thought of your father, who had married me despite my past.