Startup: An Insider's Guide to Launching and Running a Business (12 page)

Read Startup: An Insider's Guide to Launching and Running a Business Online

Authors: Kevin Ready

The conundrum here is this: should OJC follow fast, lopsided growth? Or maybe choose slower, diversified growth? Following the diversified route, there is less risk from any one customer picking up and leaving, but lower profit potential over the short term. Our aggressive CEO may choose to take the deal, but prioritize the quick acquisition of more sales outlets to create a

diversification structure that would support the company if it were to lose the large contract.

_________________

The Precious Slice

You advertise. If you

work hard

to market your product, if you spend the required time and money to put your brand and your message in front of your target audience, then something miraculous will happen: you will earn a

precious slice

of your customer’s attention. It will probably be a small slice.

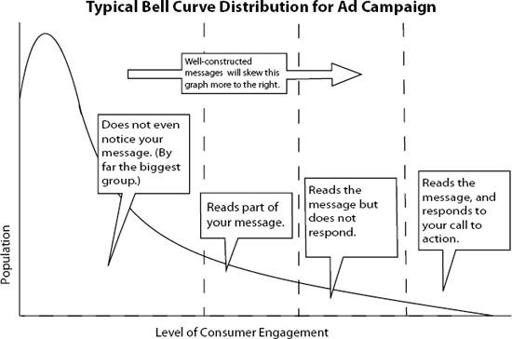

Figure 3-1.

Most recipients of your message are not going to respond in any way. By creating well-formed and appropriate messages, you can increase the rightward skew of the distribution

This little moment of attention, this precious slice of thought, when combined with the right message, is what pulls people out of the zone where they don’t know and don’t care and eases them into the first steps of becoming your customer. (This is the hook that transitions people from left to right in

Figure 3-1

.) This is an opportunity. This is

the

opportunity that your business depends

on. So what compact, well-formed, and compelling message will you put into that small, fleeting opening into your customer’s consciousness?

The precious slice demands that your message:

- Be compact.

- Be simple.

- Be resonant to their experience.

- Have a specific intention. What do you want them to do?

- Perform an action, such as calling you?

- Feel an emotion?

- Remember your name or logo?

- Learn your name?

- Buy your product?

- Get interested and follow up for more information?

- Come into your store?

- Perform an action, such as calling you?

In previous years, we carried out large-scale testing of our messaging when buying online pay-per-click advertising. By using a simple performance analysis, we determined that there were significant numerical advantages to including or excluding specific words in our ad copy. Adding an individual word could increase the performance of a 20-word ad by 5 percent. This means that a one-word difference between two similar-looking ads could mean over $100,000 difference in value in just a few months. Such is the power of finding the best message. The same evaluation applies to every place where you put words or images in front of your customers. The following examples are vital:

- What text and images you place in your advertising

- What calls to action you use and where you place them

- What your sales team is trained to tell customers

- What your employees in a retail store are trained to say

- How signs are constructed inside and outside of your retail location

Every possible variation of every message you put in front of a customer will have an effect. It is incumbent upon you to reach out and try to get a handle on what that effect is, and to find the most effective, informative, and value-creating message to use when you get that precious slice of your customer’s attention.

More than anything, avoid saying too much or assuming your marketing targets know anything about you. The tendency I have seen is to try to impart all of the great stuff you have built into your product in one avalanche of details: “We do this and we do that and you save money and it slices, and dices, and wow—can you believe version 2.0 has the new doodlydad with print capability and … and … and …”

Pick the most compelling part of your story and share a simplified, distilled version of it when you get that precious slice of customer attention. Use it as a hook to get to the next step of the conversation. Then provide more details as the customer comes in for a closer look. Your critical messaging will often be at least in part, and answer to the question asked in the next section.

_________________

Why You?

This is a question that you will need to answer. It is a question that every potential customer has in store for you, and something that you should be prepared to answer early on. A good friend of mine has been working on a micropayment platform for online commerce for the past couple of years. Early on he asked me for some input on his project, and one of the first things I asked him was rather blunt but meant to provoke thought: “Why you? Why not Google? Why not Amazon? If you want to be a platform for companies and individuals to use across the Web, how will you explain why it

needs

to be you, why it

must

be you? Why not the other really large (and well-known) players in the market?” It may be worthwhile to note that he could not convincingly answer that question, and has made a pivot or two since that time.

The “why you?” question is intimately related to the fact that most products and services can begin to fall into the parity product category if you let them. With most business models, there are multiple other options in the market

that you will need to compete against to earn a customer. Take a look at pizza. How many different pizza options do you have within 10 minutes of where you are right now? Pizza is available via home delivery, Internet delivery, local restaurants, and chains such as Domino’s, Pizza Hut, and Papa John’s. A customer

could

even decide to head to the kitchen and make one from scratch. How many pizza brands can you find in your local store? Your grocery store probably has 30 different options for frozen pizza. Any which way you turn—pizza is everywhere.

Take a moment to think about all of the messaging you get for this one product on TV and the radio, in the newspaper and junk mail coupons, and from signs at the grocery store. All of this messaging is aimed at differentiating products from one another on some facet of the pizza experience:

- Taste

- Price

- Convenience

- Emotions (e.g., fun)

- Quality

- Local exclusivity

Just as with the pizza industry, you will have to differentiate yourself in some way to stand out, to get customers, and to grow a defensible position from which to operate.

_________________

The Internet Is Not Magic

Don’t believe that the Internet is a magic solution to any business problem. It is much like any normal marketplace, but with a lower barrier to entry and potential global reach. If you look at your laptop computer, plugged into the World Wide Web, and feel electrified by the possibilities represented by that connection with so many other people, then we both have something in common. I feel it too.

Even though the Internet is a miracle of technology that has revolutionized communication and commerce, know that it is still governed by the same laws of economics that have controlled business since the earliest days of man. Remember the dot-com bubble and what were called

new economy

companies? This time saw the emergence of a large number of companies that thought that they could ignore many of the traditional laws of economics, get aboard the Internet, and ride it to wealth on the power of pure enthusiasm and limitless financing. The dream didn’t last. People woke up as soon as their financing started to run dry and they realized that investors would want to see real income in order to be convinced to invest more. “No income” meant “no business,” and Icarus fell to Earth with a big thump.

Traditional business (pre-Internet) was bound by distance. Limiting? Yes. But it was also

empowering

. Let me paint a picture of circumstance for you to visualize about the Internet. For our example, let’s consider something traditional and cast our minds back to about the year 1750. How about looking at the business model of a cooper? (A cooper was a person who made barrels for storing materials such as gunpowder, liquids, and foods.) To survive in his local marketplace in 1750, our cooper must:

- Offer a service or product that people value. People need barrels.

- Have enough potential transactions in his local market to survive. This means a population of people within trading distance, who produce food or store liquids in such quantity that they regularly need barrels. A barrel might last anywhere between one and five years, so our cooper has to take that into account when looking for repeat customers.

- Build and maintain a good reputation. If you were known to be a cooper that once used outhouse planks to make barrels, folks might not want to buy from you.

- Find the right balance between demand and supply. For example, 40 coopers in a 40-barrel-per-year market won’t work.

- Be able to source materials for making barrels. That means iron for the metal rings, wood for the barrel planks, and wood for making fires to dry the planks and heat the metal if necessary. If any of these materials are completely unavailable (e.g., in Antarctica), the cooper would be in the barrel-

importing

business, not the barrel-making business.

Because it’s 1750 in this thought experiment, the cooper doesn’t have access to global markets. He cannot (easily) sell his product to Paris, London, and New York at the same time. He is pre-Internet, pre-airplane, and pre–steam power. This is

local

in the most profound sense of that word.

I said that a local market is empowering a moment ago, did I not? I say that because of these two factors:

- Information is simple and available.

- Consumer options are limited.

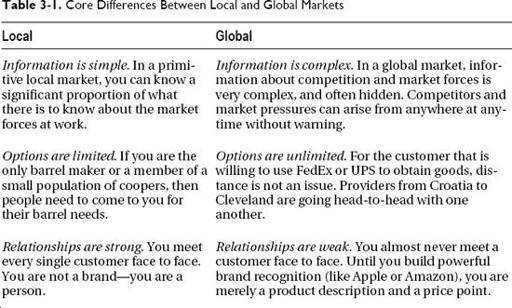

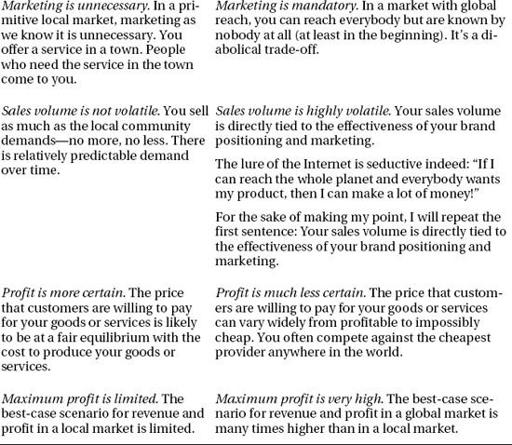

Table 3-1

describes some of the chief differences between doing business on a local scale and a global one.

Looking at this comparison, we begin to see that

marketing is a response of business to weak relationships, distance, and customers having multiple options for a product or service

.

Takeaway:

Limited distance restricts your reach, but it also means that you only have to compete with the locals. The Internet gives you access to a global audience, but also competitive exposure to any Joe with the same idea you have—worldwide.

_________________

Parity Products and the Bozo Factor

Abandon all hope ye who enter here.

—Dante

A

parity product

is something non-unique, such as books, DVDs, and software.

Indiana Jones

on DVD is a parity product—it is the same at Wal-Mart as it is at Best Buy. Parity products cannot compare to one another in terms of features (as they are identical), so the market has to search for other differentiating factors. Convenience is one. Customer service is another. In most cases the market will push and prod, and the most important differentiating factor will turn out to be price. When the differentiating factor is price, this overwhelming downward pressure continually pushes profit margins down—often to near (or below) zero profit. The game then quickly becomes which supplier can provide the parity product with the lowest-cost overhead. This is a terrible game to play, as everyone seems to lose (except the customers, who are happy that they got what they wanted—and cheap).