Startup: An Insider's Guide to Launching and Running a Business (9 page)

Read Startup: An Insider's Guide to Launching and Running a Business Online

Authors: Kevin Ready

Takeaway:

Search for low-cost opportunities to try to connect with your customers. Gather data to improve your business, but do not make the effort to gather data on a process or facet of your business if you know it will not affect your decision-making.

_________________

Always Get a Contract

When I look back to when I started my first real company in my early twenties, I was much the same as I am now. I am certainly older now and some would say wiser. Part of that wisdom is that at least some of my boyish naiveté has been replaced by an understanding of how people can be downright unfriendly to one another. I hate to bring this up, but I can’t paint things over when it comes to this topic. It’s something we must discuss.

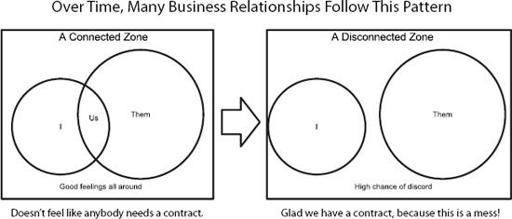

From my perspective, it comes down to psychology. Whether or not people are willing to treat each other with respect, honesty, and dignity is dependent to a large extent on whether they feel any personal identification with the other person and whether they have established and maintained a proper psychological contract. Getting along means maintaining an “us” mentality.

The problem is that even good people can fall out of this “us” paradigm very easily. Things happen, and communication is a very difficult thing to maintain.

Especially when money is on the line, relationships and understandings can be stretched or torn apart.

Take the following scenario as an example. You start a business with a business partner. Later, the business has problems. You think they are his fault and thus feel comfortable telling anybody who will listen that he is not the person he used to be. Your partner meanwhile thinks the problems arose because you are always out of town, traveling with your wife to Rolling Stones concerts. What we have here are people who, through a natural course of events, have come to a place where they no longer see eye to eye. Who is right? It depends on where you are standing, as both appear ‘right’ from their own vantage points. This imaginary scenario is a simple illustration of how one-time friends can come to a cold place where they want to sue the living daylights out of one another.

In another instance, a good friend of mine earned a share in a company over several years, to be fully vested upon its sale. A great deal of work went into building the business into something worthy of acquisition, which eventually came. When the sale was completed, no mention of the equity vesting was ever offered. When he brought it up, he was told that due to the fact that it was an asset sale and not a sale of the actual company, there would be no payout. The fine print here is that the company was never ‘sold’ per se, but all the assets were—leaving the company only a name on a piece of paper with no residual value. That’s great, isn’t it? No two ways about it, the people who had worked and struggled for the company felt … how should I say this in a polite manner? Well, that they had not been treated fairly. In this case, he did have a contract, which was plain and to the point, but not written in a way that fully protected him in the situation at hand. He had thought that a big contract was unnecessary because the owners were “good folks” that looked him straight in the eye at meeting after meeting for years—and had agreed to equity sharing.

I can only imagine what the owners of the company who got millions of dollars in the transaction were thinking. Mind reading is a dangerous thing, but they likely felt that they always treat people fairly and that the employees in question had actually failed to deliver in some way.

Everybody considers themselves to be justified in their actions. All of this is a matter of perspective.

Figure 2-5.

Time and lack of effective communication can lead to problems that nobody wants

Another recent instance comes to mind. I met a gentleman in Albany, New York who is a lobbyist working with the state government. He, in his suit and tie and with his youthful enthusiasm, is the only employee of a small firm, and he works under the owner. This young man works for $200 per week. His story is that he is willing to work for less than the minimum wage because the company is going to grow, and his boss “takes care of him,” as he put it. The boss buys him lunch most days and gives him an extra Hamilton or two when he needs it. In listening to this, I started to get a bit agitated. I asked the question, “Does your boss

need

you in order to continue his business? Are you critical?” The answer was a decided yes. Furthermore, since the boss “takes care of him,” my friend believes that he is going to be taken care of when the business grows into something bigger. My advice to him was, “Get a contract.” Directly communicate that the only way to move forward is to trade “fair value for fair value.”

I told him this, “You should expect an equity share to compensate for the lack of a living wage, and the fact that you are critical to the business.” I also told him that he should directly ask for it in a fair, level-headed, transaction-minded way. The likely outcome otherwise will be that the young man diligently puts in his time, grows the business, and then gets handed his walking papers when he asks for any special consideration later on. Never count on your boss agreeing with you that your effort was critical to the success that created the business, after all is said and done—it is not going to be visible to him in the same way it is to you.

Peter, a good friend of mine put it succinctly when he said, “Emotion has no place in business.” Clearly, people, as emotional beings bring emotion to

everything they do, but he means that you should lock down your understandings and agreements in a contract or written form so that the ambiguity of emotional decision making can be held in check.

So, I say this to anyone who will listen:

- Never rely on abstract ideas like “good feelings” or beliefs like “they are great people” or “I feel like I can trust him” in business. These are important things, but they are not sufficient by themselves for forming the basis of real and reliable business relationships. Assume that the worst will happen.

- Get a contract to define roles, responsibilities, ownership, and financial details for any aspect of the business that has value.

- Have your contracts reviewed by an attorney that represents you as an individual–distinct from the company.

- Remember that nothing changes things like money. If your business becomes valuable, you will be thankful for having worked out everything between the people involved well in advance.

Create value together with your partners and build something that benefits everyone in powerful ways, but put a mechanism together that protects you.

_________________

Watch Intellectual Property

Intellectual property is important. It is easy to get in trouble when you don’t remember this. With the quick availability of information, images, video, opinions, software, and any other kind of human output that you can imagine on the Internet, it is easy to forget that much of this content is owned by people or companies that are serious about protecting it.

By 1999, we were running a whole network of online sites similar to Match.com. On one of the home pages, one of our guys did a rework of the layout, with large images of happy people that would randomly change out each time you visited the page. The layout looked great and people liked it. Our conversion of traffic from visitor to member went up a small percentage with the new design.

A few weeks after this new interface went live, we got a phone call, followed by a letter from a legal firm: “You are using our unlicensed images—remove them or be taken to court.” They sent a detailed list of the “borrowed” images that were being used on our site. The guy who had redone the site had decided not to properly license the images he was using and instead just downloaded them and put them in the layout. We were looking at potentially thousands of dollars in attorney fees and civil penalties in court, so what looked like a time- and money-saving shortcut ended up taking executive time to respond in emergency mode, as well as a potential capital-draining sortie into an unnecessary and unproductive legal quagmire. Not good at all. I would have fired the guy who did it, but he was my business partner. Bad boy! As it was, we were able to diffuse the situation. We immediately removed the images and were lucky that they were not interested in pursuing the matter.

In an exploratory venture, we started a business producing products in China and selling them nationwide in the United States. Our first trans-Pacific freight container of products ended up being unsellable because of a claim of trademark infringement from a competitor. I will never forget what our contact at the Chinese manufacturer said: “We just make the product. It’s not our responsibility to check and make sure it’s legal to sell it in your country.” Touché. Just imagine a warehouse full of product, and not being able to sell it. A word printed on the stuff was registered as a trademark by somebody else. It hurt. A lot. We ended up letting the competitor send over a truck and load up every last crate and take it from us. At least they paid for the shipping. We felt grateful to be done with it.

The lesson is this: intellectual property is important. Avoid any easy or obvious landmines, but remember that if you are visible enough, people will come after you whether you have done anything wrong or not. Just have a good lawyer and be ready to invest money in your defense.

_________________

Control the Money

Don’t depend on any one connection point to your customers (or their money) too heavily. Don’t depend on any one mechanism (like a single credit card merchant account) to funnel your money.

If you have money flowing into a merchant account, or another payment account that third-party agencies have access to, never leave any amount of money there. Always put it in another account as soon as each deposit is made.

Back in the days when we were running the social networking firm, we charged around $30 per month for people to join. (This business was very similar to Match.com.) After a year or so, we had nearly a million registered users—not all of them paying—but only after a long process of gathering members a few at a time at first, then by the hundreds, and then by the thousands per day.

This business model was based on the concept of

rebilling

. We would charge a new member for an initial membership, and then in subsequent months the same amount would automatically be rebilled on their credits cards until they cancelled. This meant that our income would tend to increase every month, since most members would stay with us for at least six months.

I was in Japan over the Christmas break when I got a call from my business partner, Sterling, who was manning the fort back in the United States. He was not in a good mood. He had checked the company mailbox on Christmas Eve and found that we had been sent a cancellation letter from our merchant account underwriter. We were losing our ability to process credit cards—along with all of the thousands of other Internet-based customers of this bank. They decided to cancel all of the Internet customers in one fell swoop, and to do it over the Christmas holiday. They were giving us 30-days notice of cancellation, thoughtfully sent out in the Christmas mail rush on the 14th of December.

The consequence was that we had to sit on our hands and wait until January before we could even attempt to remedy our situation. Around January 4, the banks started to open again and we tried to apply for a new merchant account with another provider. Since the bank that cancelled our account also dropped thousands of other Internet-based businesses, there was a mad dash in the new year for merchant accounts, and banks were suddenly charging $1,000 or more for an application fee because of the sheer volume of applicants surging through the system. We made the decision not to pay this kind of extortion money on principle.

January 14th came and went. Our merchant account was suspended. No new merchant account was forthcoming. It was February before banks started to talk to small businesses again. When we finally got in the door with a bank and were working through the paperwork, we provided the paperwork for our

previous merchant account. This is the point in the narrative when a good storyteller would pause dramatically and say something like, “And you aren’t going to believe what happened next.” The new bank declined our application because of our

chargeback rate

. This is the ratio of dollars claimed as errors by customers to the total amount of charges billed. If this ratio went over 1 percent, you were considered to be in the “red zone.” We were informed that we had an “infinitely high chargeback rate” of $120 (one or two customers who did not recognize the Meridian IS charge name on their statement) divided by $0 of transactions in the last month. We explained what had happened, but we were not able to secure a new account in time to keep our earned base of rebillable clients intact. The bank officers didn’t care. The enforcement of this policy (without exception and without discussion) was surprisingly rigid. The business would live on, and we got payment mechanisms in place again, but the fluid transition of our accumulated rebillings portfolio was made very difficult. This cost us quite a bit of money.