Startup Weekend: How to Take a Company From Concept to Creation in 54 Hours (12 page)

Read Startup Weekend: How to Take a Company From Concept to Creation in 54 Hours Online

Authors: Marc Nager,Clint Nelsen,Franck Nouyrigat

The time limits that Startup Weekend places on participants forces them to narrow their tasks down to the most vital ones. As one participant reported, “Startups thrive only when there are constraints. By locking ourselves into this weekend-long sprint, we were forced to make tough decisions and refine the problem, solution, and market down to their very essential cores.”

Eric Koester—a veteran Startup Weekend attendee and now cofounder of Zaarly (a marketplace where people can buy and sell products or services from each other on the spot)—says, “It is critically important to understand how short a time 54 hours really is. Basically, you need to have a minute-by-minute plan of what's going to happen and what it's going to take to get something that you can showcase on Sunday night.” He recommends visualizing the presentation and then “working your way backward.” If it seems too overwhelming, then you just have to pare back. “Start pulling out the gasket, the fan—all those kinds of things [that allow you to] have an engine that will turn on and [give you something to] show to the audience.”

Nicholas Gavronsky, whose team at Startup Weekend New York City created Animotion (now an iPhone app) says that simplicity was the key to their success: “We came up with hundreds of ideas and additional features. Many [people assume that] the more features you add, the better [the end product will be].” But Gavronsky and his team disagreed. “Too many features overwhelms users and takes the focus away from what you are trying to do. Ultimately, you need to [concentrate] on the core of the idea, iterate, and launch the most simplistic version.” Of course, you can always build it out later on.

The final aspect of experiential learning that we have found to be important is the instant feedback it frequently provides. A formal classroom setting usually requires you to turn in assignments every so often to get feedback from a professor. If you use some of the principles we discuss in the next chapter, you will find that you can get immediate input from many different people (i.e., potential customers) about what you've built, or even what you're planning to build. Sorting through that information—and some of it may be contradictory—is a difficult process. However, there is no substitute for learning it firsthand and turning back to apply it to your project.

Nick Seguin, who says that attending Startup Weekends is like a drug for him, has been amazed at what people will teach themselves under pressure. “There's a necessity part of the experience; I can't get anyone else to do it, so I'm going to Google things, look them up, and figure out how to do it myself.” Because time's a wasting!

Braindump

So, let's get back to the actual Startup Weekend experience. The first thing we ask participants to do is a

braindump

. Friday is a late night at Startup Weekend. The teams often aren't assembled until after 10 PM; however, people are excited by then and want to start working. The beginning of any startup should involve getting all the ideas on the table. It's the group leader's job to make sure to give others a chance to offer their feedback. It's important to set the tone early for letting everyone have a chance to give input. At the end of Friday night, we find the whiteboards in the room are covered with lists and diagrams. Looking at these is a good way of understanding how ideas truly evolve.

Sometimes this braindump can result in a complete change of plans. For example, we witnessed one team begin with the idea of creating a mobile application for bars. As you walked around a neighborhood, it would tell you what bars were nearby and what kind of drinks they were offering. Bar owners could send coupons instantly to the app's users to attract them to their establishments.

However, after doing a little digging on Friday night, this team realized that someone had just created this application and released it two weeks before. And they had done it really well. The team tried to think of ways to improve on what was out there, but ultimately decided to go in another direction. They looked at three other possible ideas that various members suggested. One was too technically difficult to accomplish quickly, and another didn't seem as marketable.

Finally, they arrived at their idea for Quotify. This was a site that would allow users to type in funny remarks that their friends made, take a picture of them, and then—after some random interval had passed (four days, four weeks, whatever)—the site would send users back their friend's funny quotation.

The team members determined that it would be possible to design such a site over the course of a weekend, and that there was a market for it. They explained that what would distinguish them was the lack of immediacy. Usually when your friends say funny things, you can tweet them or post about them on Facebook. However, those quotes often get buried in the endless feed of other updates. So wouldn't it be great if these funny moments could come back to you at a later date? They would help to facilitate running jokes among friends.

The idea didn't win that weekend, but the team worked very well together. Because there were only six members, they were stuck in one of the smaller spaces available—a cramped, windowless conference room—for hours on end. They would open the door to get some air and then close it again when they wanted to practice their presentations or discuss strategy. The team's leader was good-natured, and even when they started feeling pressure on Sunday to get everything in order, his self-deprecating humor helped. When it came time to prepare their presentation, they wanted to use a voice recording with sound effects. Two of the team members had a vague sense of how to use the program Garage Band, but they had to work together because neither of them knew it thoroughly. It would be easy to see this team working together again—whatever their next idea might be.

A woman on the team, who had a background in business development, said she had come to one previous Startup Weekend, but her team there was plagued by drama the whole weekend. The team leader apparently got a call from an investor at AOL at some point during the weekend and started badmouthing the other team members. Nothing came of it; needless to say, investors didn't want to hear about the team's internal disputes. And the other team members were pretty angry at the team leader for going behind their backs. These sorts of stories are rare at Startup Weekend, thankfully, and we do everything we can to make sure that people understand the atmosphere of trust is one we have to protect. It is true that some teams just have better chemistry than others; again, it's just like dating. However, if you focus on the task at hand instead of your next move as an individual, success is more likely.

The environment of Startup Weekend—namely, the fact that it

is

a competition—does help to bond a team together more quickly. As one Startup Weekend Baton Rouge participant told us, “Tension is an understatement during these 54 hours. Reality TV shows could probably be filmed from these events, as the competitors are very intense and focused. Some people might try to tell you that they are there just to learn, but don't be fooled; we are entrepreneurs! Competition is in our nature, along with thirst for recognition.”

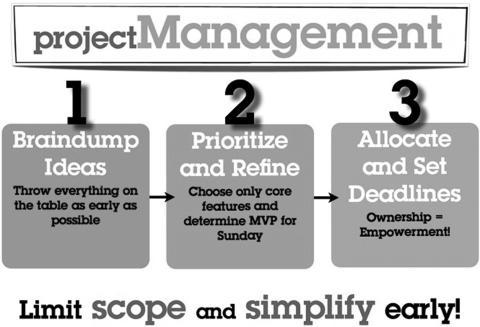

So You Have a Viable Idea—Now What?

Once you have something that looks like a viable idea, it's time to quickly refine and prioritize. What is the most important aspect of this product? There are at least two schools of thought at Startup Weekend on this question. Some people say the most important thing is to

build something

during the course of the weekend. Indeed, many Startup Weekend participants are builders by nature and by profession. They come because it's fun to build—and to build quickly. They want to test the limits. And they feel like unless you can give customers something to try out, you won't know how to move forward with your business. One of the guys who believed in this very strongly built a system that would complete the conference calling function described in Chapter 2. You simply schedule a call in your Google calendar, and all of the phone numbers on the list would be called and then connected at the appointed time. He demonstrated exactly how it worked for everyone on Sunday night.

The other school of thought is that you need only come out of the weekend with a well-developed idea. Just put up a website offering an idea for a new product or service and ask people if they'd like to buy it. Get people to sign up and tell them you'll let them know when it's ready. Then you'll have some clue about what people want and you won't even have to waste the energy and time and money on building it. This is what business theorists call a proof of concept.

We encourage people to go one step further at Startup Weekend and build what's called a minimum viable product. Rather than just having a website that shows people what the product will do once it's built, go ahead and build a stripped down version of it. As one of the pioneers of this theory, Eric Ries, explained in an interview with Venture Hacks, “The idea of minimum viable product is useful because you can basically say: Our vision is to build a product that solves this core problem for customers . . . we think that . . . early adopters [of] this kind of solution will be the most forgiving. And they will fill in the features that aren't quite there in their minds if we give them the core, tent-pole features that point [in] the direction of where we're trying to go.”

Dan Rockwell, who has launched a number of startups and participated in a Startup Weekend in Columbus, Ohio, offers a concise way of thinking about minimum viable products: They should be products with the minimum value, the minimum desired experience, the minimum cash lost, the minimum BS to endure—and the maximum momentum to burn.

Rockwell's company, Big Kitty Labs, produces something called

Protobakes

, which are “functional code examples” of something you want to make at the level of a minimum viable product. He sees these protobakes as a means of facilitating conversation between you and your team, as well as your customers and your investors. To think about a product's growth as a kind of conversation is to understand how quickly and nimbly its development is coming along. As it is when people are talking back and forth to one another, the product model can turn on a dime. This is called

pivoting

.

We talk more about how to get this feedback from early adopters and some of the other methodologies you will see in action at Startup Weekend in the next chapter. For now, suffice it to say that teams at Startup Weekend need to figure out what they can accomplish with the time, resources, and talent they have.

Learning by Doing

Whether or not Startup Weekend participants develop their ideas fully into functioning prototypes by the end of the event, they are always learning by doing. Startup Weekend offers true experiential education. In fact, one graduate of California Polytech told us that this was the aspect of Startup Weekend he most appreciated. As someone who came “from a learn-by-doing environment,” he explains that he particularly liked how Startup Weekend is not only showing people how to unlock their entrepreneurial potential, but “letting them try it in a way that shows them that they truly can make their dreams happen.” While this individual had attended a number of seminars in school where entrepreneurs had come to

speak

about their experiences, he said it was something else altogether to try out a new business “right then and there.”