Startup Weekend: How to Take a Company From Concept to Creation in 54 Hours (13 page)

Read Startup Weekend: How to Take a Company From Concept to Creation in 54 Hours Online

Authors: Marc Nager,Clint Nelsen,Franck Nouyrigat

Bo Fishback, cofounder of Zaarly, says he had seen just about every idea out there to encourage the formation of startups in his former role as Vice President of Entrepreneurship at the Kauffman Foundation. Any program that tried to support entrepreneurship inevitably came to Kauffman looking for financial support. He says it is the experiential learning component of Startup Weekend that sets it apart from the rest, even calling Startup Weekend “the single most powerful force for good on planet Earth.”

Fishback, who recently left Kauffman to work on a startup that was born at Startup Weekend, explains why our model is distinctive. Though he has an MBA from Harvard, Fishback believes that he learned about a third as much about startups in two years at Harvard as you do in a Startup Weekend. He calls experiential education “the magic ingredient.”

Historically speaking, in order to get that experiential education, you had to take a big risk, gamble on a lot of things, and go and work at a startup. You had to quit your job to build a company, or do it in your basement at night and make your spouse mad. Now, there has been a convergence of forces to change that reality.

It's not like Startup Weekend did this singlehandedly. Elements like the availability of technology, the Internet, development tools, and social networking have all contributed to the current environment. What Startup Weekend adds is the practical layer that ties all of that other stuff together.

But there has also been a change in the perspective of young people today, says Northwestern's Michael Marasco. “These are students who live in families where Mom and Dad don't have lifetime employment. They have been restructured, or let go for reasons that were outside their control—and in many cases, it probably had significant [financial and social] impacts on their family.” Marasco believes that situation has encouraged his students to “take more control of their lives” by exploring entrepreneurship.

One Startup Weekend participant in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, tells a story of coming to this revelation about entrepreneurship later in life: “I've spent a lifetime working in bureaucracies, not knowing how to break free. But entrepreneurship always tugged at my soul, telling me there is something better to aspire to; [that] there are people who strive for more . . . who are encouraged by their successes and wiser for their failures.”

Risk Mitigation

Fishback acknowledges that there is plenty of chaos in the 54 hours of Startup Weekend. But at some point, “You get to piece together what it actually takes to be smart about building a company.” Society likes to think of these startup founders as Great Wild West, gun- slinging risk-takers who go out there and hit the right nerve at the right time, and all of a sudden become Bill Gates. There tends to be a certain kind of lore built up around legendary entrepreneurs—how they risked everything on that one brilliant idea.

However, Fishback thinks that those kinds of stories are “total bullshit, actually.” Of the thousands of entrepreneurs with whom he has worked, most seem to be “people who are successful and not just lucky—[who] are actually the great

risk mitigators

.” Startup Weekend does attempt to be a tool for alleviating risk. It provides entrepreneurs with some visibility, some exposure to schools of business thought, different kinds of human beings—all the elements that essentially let people “try before you buy.”

People who become successful entrepreneurs are most often the ones who look into this big cloud of ambiguity—and then, by taking a little step in and looking around, discern whether they can eliminate some of the ambiguity, and then take another step in. This is the process of learning as you go, taking account of the feedback you get from customers, from the market, from the environment—and planning your next move accordingly.

That's why the presentations on Sunday evening often sound different—sometimes entirely dissimilar—from the pitches on Friday night. Some ideas change so completely because participants must undergo the process of discovering what customers want, and what real needs are out there. This is actually all part of that risk mitigation. But the great thing about Startup Weekend is that you can go accomplish this process in 54 hours instead of five years.

The blogosphere and scores of social networking websites have profoundly changed the way we transmit information. Nowadays, you have at your disposal the ability to test ideas, reach distinct communities, and talk to specific customers. One of the reasons the last Internet bubble ended up being a bust is that people were taking risks without gathering, and utilizing, enough of that kind of feedback. Sure, there were a few big successes. But much smarter companies are being built today. It's entirely possible to think to yourself, “Hey, I'd like to try out an idea. Let's see if the market will like it.” And you don't have to wait years or months to find out whether your plan will work; it's a matter of days or even hours. We predict that this kind of information gathering will lead to a real entrepreneurship boom.

One startup veteran told us that he was particularly appreciative of the “brutal feedback” he got from other Startup Weekend participants: “[It's] the kind of feedback that makes you reexamine everything that you are doing, [and] that makes you restart and redo everything you've done over and over again.”

The team that built the Internet-TV application decided not to have a live demo of the video chat feature when they introduced their product Sunday night. They reasoned that everyone knows this technology is available. Therefore, they decided to focus instead on getting the application (which displayed what someone's friends were watching) up and running, and then just show people via a slide where the video chat would pop up on the screen.

Allocating Tasks

Once you determine as a team what you can get done in a weekend, you then need to allocate the tasks amongst members. In some cases, it will be obvious who should be doing what. Coders will code. People who specialize in business development will research what else is out there and get customer feedback. Design people will probably be pulled into various different projects. But ultimately, we recommend coming up with a list of discrete tasks and displaying it where everyone can see.

Some teams use the concept of a scrum board in order to show what has been done, what is being done now, and what needs to be done. One advantage of this approach is that everyone on the team knows where things stand. It means that if you want to begin working on a task but feel you can't get started until someone else completes his task, you know to whom you should talk. You keep the workflow going and don't allow it to get bottled up in any one place.

* A basic scrum board shows the status of many tasks that are in a team's pipeline all at once.

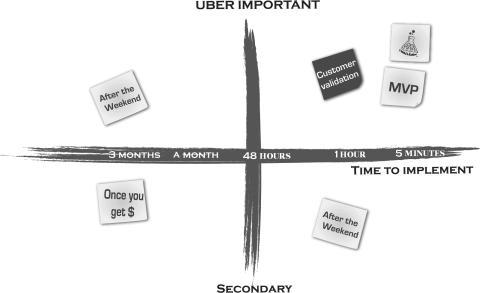

Another idea we recommend is an

urgent and important matrix

: a diagram of four squares with one axis labeled

important

and the other labeled

urgent

. Looking at where tasks fall in this matrix makes it immediately obvious what you should be working on

right this minute

.

Here Is the Order in Which You Should Complete Tasks:

1.

Urgent and important

2.

Important but not urgent

3.

Urgent but not important

4.

Not urgent or important

Once you prioritize as a team, everyone should be clear on what he or she should be doing individually. Giving each person his or her own area in which to work means that everyone will take ownership of their respective tasks, and feel empowered to complete them.

We also recommend that each person only work on one task at a time. The more people are distracted by other priorities, the less effective they will be. Everyone should have a discrete project they are tackling, and it should be in line with the group's overall priorities.

The team leader doesn't have time to be micromanaging everyone; and it's a waste of time for him or her to do so, anyway. If you've put together a group of competent people, let them do their jobs and arrange them in such a way that people don't have to ask permission to go to the next step.

People are always thinking about deadlines at Startup Weekend, and Sunday at 5 PM is always looming. Admittedly, we do try to pack a lot of work into two and a half days. However, this helps to affirm the view we strongly take: that every entrepreneur should always be thinking in terms of deadlines. You want to constantly set short-term goals—something that you can accomplish in a couple of weeks. The further away you make the deadline, the less accountable you will be. So be realistic about the amount of time, but challenge yourself a little, too. After all, we live in a fast-moving business environment. Sitting on an idea for months or a year while you find large chunks of time to work on it will ensure that your competitors will pass you by.

When you're working in the real world, we recommend checking in with your team daily or once every few days. However, people should check in every couple of hours at Startup Weekend. You don't want your team members to waste time going off on the wrong track or to get stuck on a problem that other people may be able to help solve.

Of course, there is always the potential for disagreement on matters that do require the whole group's input. If you've ever been called for jury duty, you know how long it can take for a committee to make decisions. When you assemble a team of smart, informed, and friendly people, you could sit around all day discussing which strategy to take. In fact, we have seen teams spend Friday night and all of Saturday talking about what will work and what won't. Our advice: Don't get sucked into extensive debate. Set a timer for the discussion; talk about an important decision for 20 minutes. If it's not that critical, allow 10 minutes and then take a

Roman Vote

: Everyone gives a thumbs-up or -down. Then, don't look back. Fortunately, moving ahead in startups doesn't always require unanimity the way a jury does. So, see what the majority says—and then move on.

Recognizing Failure