Stiff (18 page)

Authors: Mary Roach

One group recently braved the storm. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Harris and a team of other doctors from the Extremity Trauma Study Branch of the U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, recruited cadavers to test five types of footwear either commonly used by or being newly marketed for land mine clearance teams. Ever since the Vietnam War, a rumor had persisted that sandals were the safest footwear for land mine clearance, for they minimized injuries caused by fragments of the footwear itself being driven into the foot like shrapnel, compounding the damage and the risk of infection. Yet no one had ever tested the sandal claim on a real foot, nor had anyone done cadaver tests of any of the equipment being touted by manufacturers as offering greater safety than the standard combat boot.

Enter the fearless men of the Lower Extremity Assessment Program.

Starting in 1999, twenty cadavers from a Dallas medical school willed body program were strapped, one by one, into a harness hanging from the ceiling of a portable blast shelter. Each cadaver was outfitted with strain gauges and load cells in its heel and ankle, and clad in one of six types of footwear. Some boots claimed to protect by raising the foot up away from the blast, whose forces attenuate quickly; others claimed to protect by absorbing or deflecting the blast's energy. The bodies were posed in standard walking position, heel to the ground, as though striding confidently to their doom. As an added note of verisimilitude, each cadaver was outfitted head to toe in a regulation battle dress uniform. In addition to the added realism, the uniforms conferred a measure of respect, the sort of respect that a powder-blue leotard might not, in the eyes of the U.S. Army anyway, supply.

Harris felt confident that the study's humanitarian benefits outweighed any potential breach of dignity. Nonetheless, he consulted the willed body program administrators about the possibility of informing family members about the specifics of the test. They advised against it, both because of what they called the "revisiting of grief" among families who had made piece with the decision to donate and because, when you get down to the nitty-gritty details of an experiment, virtually any use of a cadaver is potentially upsetting. If willed body program coordinators contacted the families of LEAP cadavers, would they then have to contact the families of the leg-drop-test cadavers down the hall, or, for that matter, the anatomy lab cadavers across campus? As Harris points out, the difference between a blast test and an anatomy class dissection is essentially the time span. One lasts a fraction of a second; the other lasts a year. "In the end," he says, "they look pretty much the same." I asked Harris if he plans to donate his body to research. He sounded downright keen on the prospect. "I'm always saying, 'After I die, just put me out there and blow me up.' "

If Harris could have done his research using surrogate "dummy" legs instead of cadavers, he would have done so. Today there are a couple good ones in the works, developed by the Australian Defence Science & Technology Organisation. (In Australia, as in other Commonwealth nations, ballistics and blast testing on human cadavers is not allowed.

And certain words are spelled funny.) The Frangible Surrogate Leg (FSL) is made of materials that react to blast similarly to the way human leg materials do; it has mineralized plastic for bones, for example, and ballistic gelatin for muscle. In March of 2001, Harris exposed the Australian leg to the same land mine blasts that his cadavers had weathered, to see if the results correlated. Disappointingly, the bone fracture patterns were somewhat off. The main problem, at the moment, is cost. Each FSL—they aren't reusable—costs around $5,000; the cost of a cadaver (to cover shipping, HIV and hepatitis C testing, cremation, etc.) is typically under $500.

Harris imagines it's only a matter of time before the kinks are worked out and the price comes down. He looks forward to that time. Surrogates are preferable not only because tests involving land mines and cadavers are ethically (and probably literally) sticky, but because cadavers aren't uniform. The older they are, the thinner their bones and the less elastic their tissue. In the case of land mine work, the ages are an especially poor match, with the average land mine clearer in his twenties and the average donated cadaver in its sixties. It's like market-testing Kid Rock singles on a roomful of Perry Como fans.

Until that time, it'll be rough going for Commonwealth land mine types, who cannot use whole cadavers. Researchers in the UK have resorted to testing boots on amputated legs, a much-criticized practice, owing to the fact that these limbs have typically had gangrene or diabetic complications that render them poor mimics of healthy limbs. Another group tried putting a new type of protective boot onto the hind leg of a mule deer for testing. Given that deer lack toes and heels and people lack hooves, and that no country I know of employs mule deer in land mine clearance, it is hard—though mildly entertaining—to try to imagine what the value of such a study could have been.

LEAP, for its part, turned out to be a valuable study. The sandal myth was mildly vindicated (the injuries were about as severe as they were with a combat boot), and one boot—Med-Eng's Spider Boot—showed itself to be a solid improvement over standard-issue footwear (though a larger sample is needed to be sure). Harris considers the project a success, because with land mines, even a small gain in protection can mean a huge difference in a victim's medical outcome. "If I can save a foot or keep an amputation below the knee," he says, "that's a win."

It is an unfortunate given of human trauma research that the things most likely to accidentally maim or kill people—things we most need to study and understand—are also the things most likely to mutilate research cadavers: car crashes, gunshots, explosions, sporting accidents. There is no need to use cadavers to study stapler injuries or human tolerance to ill-fitting footwear. "In order to be able to protect against a threat, whether it is automotive or a bomb," observes Makris, "you have to put the human to its limits. You've got to get destructive."

I agree with Dr. Makris. Does that mean I would let someone blow up my dead foot to help save the feet of NATO land mine clearers? It does. And would I let someone shoot my dead face with a nonlethal projectile to help prevent accidental fatalities? I suppose I would. What

wouldn't

I let someone do to my remains? I can think of only one experiment I know of that, were I a cadaver, I wouldn't want anything to do with. This particular experiment wasn't done in the name of science or education or safer cars or better-protected soldiers. It was done in the name of religion.

Footnotes:

[

1]

I did not ask DeMaio about sheep and the purported similarity of portions of their reproductive anatomy to that of the human female, lest she be forced to draw conclusions about the similarity of my intellect and manners to that of the, I don't know, boll weevil.

[

2]

MacPherson counters that bullet wounds are rarely, at the outset, painful. Research by eighteenth-century scientist/philosopher Albrecht von Haller suggests that it depends on what the bullet hits.

Experimenting on live dogs, cats, rabbits, and other small unfortunates, Haller systematically catalogued the viscera according to whether or not they register pain. By his reckoning, the stomach, intestines, bladder, ureter, vagina, womb, and heart do, whereas the lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys "have very little sensation, seeing I have irritated them, thrust a knife into them, and cut them to pieces without the animals' seeming to feel any pain." Haller admitted that the work suffered certain methodological shortcomings, most notably that, as he put it, "an animal whose thorax is opened is in such violent torture that it is hard to distinguish the effect of an additional slight irritation."

[

3]

According to the Kind & Knox Web site, other products made with cow-bone-and-pigskin-based gelatin include marshmallows, nougat-type candy bar fillings, liquorice, Gummi Bears, caramels, sports drinks, butter, ice cream, vitamin gel caps, suppositories, and that distasteful whitish peel on the outside of salamis. What I am getting at here is that if you're going to worry about mad cow disease, you probably have more to worry about than you thought. And that if there's any danger, which I like to think there isn't, we're all doomed, so relax and have another Snickers.

7

Holy Cadaver

The crucifixion experiments

The year was 1931. French doctors and medical students were gathered in Paris for an annual affair called the Laennec conference. Late one morning, a priest appeared on the fringes of the gathering. He wore the long black cassock and Roman collar of the Catholic Church, and he carried a worn leather portfolio beneath one arm. His name was Father Armailhac, he said, and he sought the counsel of France's finest anatomists. Inside the portfolio was a series of close-up photographs of the Shroud of Turin, the linen cloth in which, believers held, Jesus had been wrapped for burial when he was taken down from the cross. The shroud's authenticity was in question then, as now, and the church had turned to medicine to see if the markings corresponded to the realities of anatomy and physiology.

Dr. Pierre Barbet, a prominent and none-too-humble surgeon, invited Father Armailhac to his office at Hôpital Saint-Joseph and swiftly nominated himself for the job. "I am… well versed in anatomy, which I taught for a long time," he recalls telling Armailhac in

A Doctor at Calvary:

The Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ as Described by a Surgeon

. "I lived for thirteen years in close contact with corpses," reads the next line. One assumes that the teaching stint and the years spent living in close contact with corpses were one and the same, but who knows. Perhaps he kept dead family members in the cellar. The French have been known to do that.

Little is known about our Dr. Barbet, except that he became very devoted, possibly a little too devoted, to proving the authenticity of the Shroud.

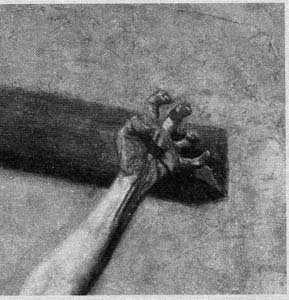

One day soon, he would find himself up in his lab, pounding nails into the hands and feet of an elfin, Einstein-haired cadaver—one of the many unclaimed dead brought as a matter of course to Parisian anatomy labs—

and crucifying the dead man on a cross of his own making.

Barbet had become fixated on a pair of elongated "bloodstains"[

1]

issuing from the "imprint" of the back of the right hand on the shroud. The two stains come from the same source but proceed along different paths, at different angles. The first, he writes, "mounts obliquely upwards and inwards (anatomically its position is like that of a soldier when challenging), reaching the ulnar edge of the forearm. Another flow, but one more slender and meandering, has gone upwards as far as the elbow." In the soldier remark, we have an early glimmer of what, in the due course of time, became clear: Barbet was something of a wack. I mean, I don't wish to be unkind, but who uses battle imagery to describe the angle of a blood flow?

Barbet decided that the two flows were created by Jesus' alternately pushing himself up and then sagging down to hang by his hands; thus the trickle of blood from the nail wound would follow two different paths, depending on which position he was in. The reason Jesus was doing this, Barbet theorized, was that when people hang from their arms, it becomes difficult to exhale; Jesus was trying to keep from suffocating.

Then, after a while, his legs would fatigue and he'd sag back down again.

Barbet cited as support for his idea a torture technique used during World War I, wherein the victim is hung by his hands, which are bound together over his head. "Hanging by the hands causes a variety of cramps and contractions," wrote Barbet. "Eventually these reach the inspiratory muscles and prevent expiration; the condemned men, being unable to empty their lungs, die of asphyxia."

Barbet used the angles of the purported blood flows on the shroud to calculate what Jesus' two positions on the cross must have been: In the sagging posture, he calculated that the outstretched arms formed a 65-degree angle with the stipes (the upright beam) of the cross. In the pushed-up position, the arms formed a 70-degree angle with the stipes.

Barbet then tried to verify this, using one of the many unclaimed corpses that were delivered to the anatomy department from the city's hospitals and poorhouses.

Once Barbet got the body back to his lab, he proceeded to nail it to a homemade cross. He then raised the cross upright and measured the angle of the arms when the slumping body came to a stop. Lo and behold, it was 65 degrees. (As the cadaver could of course not be persuaded to push itself back up, the second angle remained unverified.) The French edition of Barbet's book includes a photograph of the dead man on the cross. The cadaver is shown from the waist up, so I cannot say whether Barbet dressed him Jesus-style in swaddling undergarments, but I can say that he bears an uncanny resemblance to the monologuist Spalding Gray.