Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (29 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

Lightning conductors were not entirely trusted at first; they were believed by some to draw down upon a ship more ‘electric fluid’ than they could transmit safely to earth. Trials in 1831 demonstrated the utility of these devices, but they did not always prevent disasters. Tragedies continued to occur, especially when the ship was at an angle and other spiky protuberances such as the bowsprit and the driver boom end could attract lightning.

POOPED – visibly overwhelmed by exhaustion.

DERIVATION

: the poop is the high deck aft above the quarterdeck, found in the larger sailing ships. A ship is pooped when a heavy sea breaks over her stern while she is running before the wind in a gale – a very dangerous situation because the vessel’s speed in this circumstance is approximately the same as the following sea. She therefore loses steerage way and becomes uncontrollable as the wave rampages down her deck.

DMIRAL HOSIER’S GHOST

In March 1726 Vice-Admiral Francis Hosier was appointed to command a squadron bound for the West Indies. His orders were to prevent the Spanish treasure ships sailing home from Porto Bello. However, when Hosier’s ships arrived, the Spaniards simply sent their treasure back to Panama, leaving the galleons empty. In the absence of further orders Hosier blockaded these ships from June to December, losing great numbers of his men to the dreaded yellow fever, the ‘black vomit’.

With so many casualties to disease he was forced to return to his base in Jamaica, where the ships were cleared out and new men were recruited to replace the dead. However, the contagion remained and over the next six months, while the squadron was blockading other Spanish ports, the casualties continued to mount. Out of 4,750 men over 4,000 died.

Eventually Hosier succumbed to the disease himself, and after lingering for ten long days he died on 27 August 1727 in Jamaica, as did his immediate successors, Commodore St Lo and Rear Admiral Hopson. Hosier’s body was embalmed and brought back in the ballast of a sloop inaptly named

Happy

. He was buried in his native Deptford.

Hosier achieved posthumous fame in 1740 when Richard Glover published a poem, ‘Admiral Hosier’s Ghost’, a blatantly political piece. Glover used Hosier’s fate to support attacks on the Walpole government. In the poem (which later became a popular song) Hosier’s ghost appears to Edward Vernon, after his successful capture of Porto Bello, which had eluded Hosier.

Heed, oh heed our fatal story

I am Hosier’s injured ghost

You who now have purchased glory

At this place where I was lost.

Contemporary satirical print

Contemporary satirical print.

A

TERRIBLE SCENE OF DEVASTATION

The frigate HMS

Amphion

had just completed repairs in Plymouth dockyard, Devon, and as she was due to sail the next day, she had more than 100 visitors and relatives on board in addition to her crew, making a total of about 400 persons.

Captain Israel Pellew was dining in his cabin with his first lieutenant and Captain Swaffield of a Dutch man-o’-war. At about 4 p.m. in the afternoon on 22 September 1796 a violent shock was felt in the town and the sky lit up bright red as a massive explosion blew the ship apart. People ran to the dockyard and witnessed a terrible scene of devastation. Strewn in all directions were splintered timbers, broken rigging and blackened, mangled bodies.

At the instant of the explosion Pellew and his guests were thrown violently off their chairs. Pellew rushed to the window and climbed out. He managed to escape virtually unharmed and was picked up by a boat. The first lieutenant, too, got clear with only minor injuries. Captain Swaffield, however, perished. His body was found a month later with his skull fractured.

There were some miraculous escapes among the crew. At the moment of the explosion the marine at the captain’s cabin door was looking at his watch – it was dashed from his hands and he was stunned senseless. He knew nothing more until he found himself safe on shore, having suffered only slightly. The boatswain was standing on the cathead directing his men at work when he felt himself suddenly carried off his feet into the air. He fell into the water and lost consciousness. When he came to, he found he was entangled in some rigging and had suffered a broken arm, but he managed to extricate himself and was picked up by a boat.

Apart from Pellew, the only survivors were two lieutenants, a boatswain, three or four seamen, a marine, a woman and a child. The child was discovered clutched to her mother’s lifeless bosom; the lower half of her body had been blown to pieces.

The cause of this disaster was never established, but many believe the ship’s gunner was stealing gunpowder, which accidentally ignited.

AN OVERBOARD AND THEN SOME …

A fall from the rigging was usually fatal if the seaman hit the decks. Landing in the water he had a chance of survival if he could be found quickly enough.

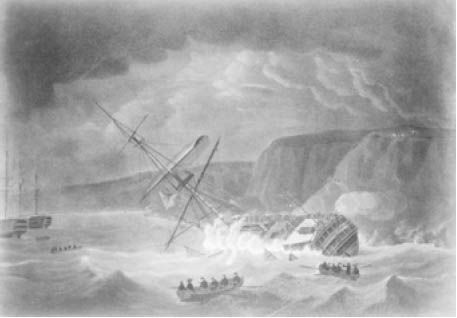

On occasion the attempt to rescue a man from the water led to greater disaster. On 24 November 1804 a signal was made for the fleet moored at Torbay, a naval anchorage in southern England, to get under way. It was a very dark night, and while raising the anchor of HMS

Venerable

a master’s mate and a seaman fell overboard. A boat was instantly lowered to try to save them, but in the confusion it filled with water and the rescue crew were thrown in the sea.

At that moment another ship loomed up in the dark and evasive action was taken to avoid collision. Then

Venerable

began drifting, stern first, into the shore and grounded on rocks and hard sand. Water poured into the doomed vessel.

The cutter

Frisk

attempted to take men off

Venerable

, as did other ships’ boats, but the weather worsened and the hulk became submerged to the upper gun deck. Then

Frisk

did manage to rescue a number of the men, and a makeshift raft enabled others to get ashore. Some of the sailors still aboard, meanwhile, believing their fate was sealed, broke into the spirit room to seek oblivion in drink.

A court martial was convened on 11 December following the loss of the ship. Captain Hunter, his officers and the ship’s company were all honourably acquitted, except for one sailor who was found guilty of drunkenness, disobedience of orders and plundering the officers’ baggage. He was sentenced to 200 lashes around the fleet.

HMS

HMSVenerable

meets her end at Torbay

.

CUTS A FINE FEATHER – said of a person who is a nifty dresser.

DERIVATION

: when a ship was sailing well her bow wave looked like a white feather.

‘P

‘PLAGUE OF THE SEA’

Scurvy was once the most malignant of all sea diseases. Painful and loathsome in its symptoms, it killed two million sailors during the Golden Age of Sail.

The disease was first observed by the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates. Physical symptoms included black-coloured skin, ulcers, difficulty in breathing, loss of teeth and rotting gums. Sometimes old wounds reopened from injuries sustained decades earlier. Scurvy resulted in strange sensory and psychological effects. When a man was in the last stages of the disease the sound of a gunshot was enough to kill him, while the smell of blossom from the shore could cause him to cry out in agony. The sufferer broke down into tears at the slightest provocation and suffered acute yearnings for the shore.

History records the devastation caused on long sea voyages. Vasco da Gama saw two-thirds of his crew succumb to the disease en route to India in 1499. In 1520 Magellan lost more than 80 per cent of his men to scurvy while crossing the Pacific. The Elizabethan sea explorer Sir Richard Hawkins cursed the disease as ‘the plague of the sea and the spoyle of mariners’. In 1740 Commodore Anson led a squadron of five warships on a four-year voyage which turned into the worst sea-borne medical disaster in history. Over half of the 2,000 men who left England with him died from scurvy, and only one vessel of his fleet returned, his flagship HMS

Centurion

.

Many anti-scorbutics that were heralded as cures were in fact useless. Among these were elixir of vitriol – made from sulphuric acid, spirit of wine, sugar, cinnamon, ginger and other spices, and Ward pills, a violent diuretic. Some believed that going ashore and being half buried in earth would result in a cure. Spruce beer, made from the leaves of the conifer, was officially issued in the North American station.

James Cook succeeded in circumnavigating the world in 1768–71 in

Endeavour

without losing a single man to scurvy. He was a great believer in regular doses of wort of malt, but this would not have been effective as a remedy. He did ensure that his crew’s diet was supplemented with fresh fruit and vegetables, but probably the one truly anti-scorbutic measure he took

was

to prohibit the eating of the fat skimmed off the vats used to boil salt meat. Cook took this measure as he believed the practice was unhealthy but we now know that fat interacts with copper to produce a substance that prevents the gut from absorbing vitamins.

The Scottish naval surgeon James Lind proved the disease could be treated with citrus fruits in experiments he described in his 1753 book

A Treatise of the Scurvy

. Scurvy was not eradicated from the Royal Navy, however, until the chairman of the navy’s Sick and Hurt Board, Gilbert Blane, finally put the prescription of fresh lemons to use during the Napoleonic Wars. Other navies soon adopted this successful solution.

Earlier experiments with the use of limes, which were not nearly as effective as lemons in preventing scurvy, gave rise to the nickname ‘limey’ for British sailors.

James Lind

James Lind.

T

HE EVENT THAT INSPIRED

MOBY DICK

By the beginning of the nineteenth century whaling had made Nantucket, Massachusetts, one of the richest localities in the United States. In 1819 the whaling ship

Essex

under 29-year-old Captain George Pollard left for the whaling grounds of the South Pacific with a crew of 20 men. The voyage was expected to take two and a half years.

On 20 November 1820 spouts were sighted, and as usual the ship gave chase and launched the dories, leaving just a skeleton crew aboard. Suddenly a huge bull whale breached, spouted and swam at high speed towards the ship, ramming it at the waterline near the bow and throwing all those on board to the deck. The creature then surfaced beside the ship, shook itself and dived again. Then it came back for a second attack and the ship rolled

over

on to her beam-ends. Hastily returning to the ship, Pollard asked, ‘My God, what is the matter?’ and was told, ‘We’ve been stove by a whale!’

Essex

stayed afloat for two days, after which the crew had to abandon ship and take their chances in the whaleboats.