Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (27 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

Generally, whistling was discouraged in ships. When becalmed, scratching a backstay and whistling softly might entice a useful breeze, but it was to be avoided if the weather was threatening to get dirty; it could annoy Saint Anthony, the patron saint of wind, and a strong blow could come on.

In the Royal Navy whistling was banned at sea, as it could be confused with orders given by the bosun’s whistle. There was one exception to this, however. When making the boiled pudding known as duff, the ship’s cook was traditionally made to whistle so that he could not surreptitiously eat the raisins destined for the popular treat.

St Elmo’s fire strikes a ship

St Elmo’s fire strikes a ship.

W

ITCHCRAFT OVER THE WATER

Witches, taking the shape of waves, have ever been the nemesis of sailors. They stop ships, turn the wind and raise general havoc, often using cats as familiars. Witchcraft was sometimes attributed to people who had good reason to feel malevolence against the ship, such as landladies whose bill had not been paid by some of the men on board.

When Anne of Denmark was crossing the North Sea in 1589, en route to marry James I of England, a coven of witches at Leith in Scotland raised a storm that interrupted the voyage. A witch hunt was instigated, and under torture a number of Danish and Scottish women confessed to sorcery. One claimed that she had taken a cat and christened it and then bound several parts of a dead man to it. In the night she and her fellow witches threw the unfortunate animal into the sea.

It was popularly believed in Scotland that the Spanish Armada met defeat on account of the witches on the island of Mull who brought the storms that scuttled many of Philip’s ships.

On trial in 1684, Edward Man of the merchant vessel

Neptune

attempted to explain his incompetence in bringing her to Milford Haven instead of London by telling the court that he had been bewitched by the ship’s cat and that it was ‘the Divell had brought them thither’.

Sometimes witches sold mariners special powers in the form of knotted cords so they could personally influence the weather. As the knots were loosened the wind increased, until at the untying of the last knot a gale arose.

Witches raise a storm at sea, sixteenth-century engraving

Witches raise a storm at sea, sixteenth-century engraving.

CHOCK-A-BLOCK – completely full.

DERIVATION

: when a block and tackle has reached the point where the two blocks come together it cannot go any further.

S

SALUTING THE QUARTERDECK

Custom dictates that in any naval ship the quarterdeck (the upper deck from the main mast to right aft) symbolises the Service and is the focus for its ceremonial. In the Middle Ages a crucifix was placed in this area, and was the first object seen when boarding a ship. Officers and men would remove their headgear at the figure of Christ, and this probably explains the practice, which survives today, of saluting the quarterdeck. A salute is also given on entering a ship, for in the days of sail coming aboard over the bulwarks would place you on the quarterdeck. The Royal Naval College at Dartmouth has a large hall, somewhat churchlike in appearance, known as the Quarterdeck, which lies at the heart of the college.

ENIZENS OF THE DEEP

Below the thunders of the upper deep

Far far beneath in the abysmal sea

His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep

The Kraken sleepeth…

Tennyson’s poem tells of the legendary sea monster said to inhabit the waters off the coast of Norway and Sweden. It was a creature of enormous size which would wrap its arms around the hull of a ship and drag it down. Sometimes it lay on the surface of the sea like an island; when a ship approached it submerged and the resulting whirlpool sucked the ship to its doom.

Other sea monsters sighted have included sea dragons and sea serpents, which could be slimy or scaly and often spouted jets of water.

Sir Henry Gilbert claimed to have encountered a lion-like monster with glaring eyes on his return voyage to England from Newfoundland in 1583.

Hans Egede, a missionary on a voyage to the western coast of Greenland in July 1734, reported: ‘[There] appeared a very terrible sea-animal, which raised itself so high above the water that its head reached above our maintop. It had a long, sharp snout, and blew like a whale… on the lower part it was formed like a snake… it raised its tail above the water, a whole ship length from its body.’

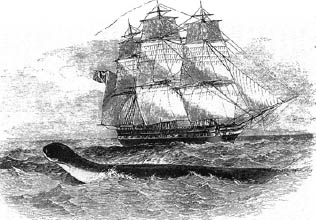

Perhaps the most famous sighting occurred on 6 August 1848, when HMS

Daedalus

was on passage to England from the East Indies. Midshipman Satoris reported seeing something very unusual in the sea to officer-of-the-watch Lieutenant Edgar Drummond. The two came to the conclusion that they had seen a sea serpent and informed the captain.

The ship reached Plymouth on 4 October. Someone on board leaked the story to the press and

The Times

printed a lively account of the sighting. Until this time the captain of

Daedalus

Peter M’Quhae had kept silent, nervous no doubt of the reaction of the navy to such a tale, and for this reason the incident had not been logged officially. However, he was ordered to report to Admiral Sir W.H. Gage, who demanded an explanation of what he had read in the newspaper. M’Quhae produced Drummond’s journal and

a

picture of an enormous serpent with head and shoulders about a metre above the surface of the sea. The creature was described ‘as nearly as we could approximate by comparing it with the length of what our main topsail yard would show in the water, there was at least 60 feet of the animal

à fleur d’eau

, no portion of which was, to our perception, used in propelling it through the water… It passed so close under our lee quarter that had it been a man of my acquaintance, I would have easily recognised his features with the naked eye…’

Daedulus

Daedulusand the sea serpent

.

The sighting caused a stir in the scientific community. Sir Richard Owen, curator of the Hunterian Museum, argued that it was a seal. Others suggested an upside-down canoe or a giant squid.

Could those aboard

Daedalus

have met a living creature of some unknown species?

HE BUZZARD’S CODE

Olivier Levasseur was a French pirate nicknamed La Buse, meaning the buzzard, for the alacrity with which he threw himself at his enemies. His greatest prize was the capture, in 1721 off the island of La Réunion, of

Nossa Senhora do Cabo

, a Portuguese vessel loaded with gold and jewels belonging to the retiring viceroy of Goa. The booty included a magnificent solid gold cross, 2 m high and encrusted with diamonds, emeralds and rubies, known as ‘The Fiery Cross of Goa’.

The 17-line cipher

The 17-line cipher.

It is believed that La Buse concealed the treasure somewhere along the north eastern coast of Mahe, the principal island of the Seychelles archipelago.

Nine years after this incredible haul Levasseur was captured and hanged. But he did not depart from life without some drama. Legend has it that at the gallows he threw out some parchment maps and documents identifying the location of where he had buried the treasure. They

were

in code, however, and he called to the crowd, ‘Find my treasure, he who may understand it.’

Several copies were made of these papers, which included a cipher containing 17 lines of Greek and Hebrew letters.

The hunt was taken up in the 1950s by Reginald Cruise-Wilkins, a former Coldstream Guardsman, who eventually believed he had broken much of the code and that the hoard lies somewhere in the vicinity of Bel Ombre on Mahe. Before his death in 1977 he passed the treasure hunter’s baton to his son, John, who continues the search for what is perhaps the greatest treasure ever to fall into the hands of a pirate. Its value today could exceed several hundred million pounds.

IN THE OFFING – about to happen.

DERIVATION

: a ship would be trapped against the land if an enemy came out of the offing. This was the sea area beyond anchoring ground but visible from the coast.

F

FAMOUS LAST WORDS

Nelson’s last words were neither ‘Kiss me, Hardy’ nor ‘Kismet, Hardy’. Both versions have a wide currency, but in fact Hardy was not even present at the moment of the admiral’s death as he had been called back on deck.