Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (23 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT THE

sea and mariners abound across history. Many endure to this day, such as the myth of the ruthlessness of the press gangs. Although often rough-handed, they were regulated as to whom they could take and certainly did not have carte blanche to drag innocent young men off to sea. Fanciful accounts of the life of that great sea hero Horatio Nelson also enjoy popular currency. His body was not pickled in rum after his death at Trafalgar, nor were his last words ‘Kiss me, Hardy’.

It is true, however, that those who follow the sea have always been among the most superstitious people on earth. Some notions, including those about the weather such as ‘when the rain’s before the wind, strike your tops’ls, reef your main’, often have more than an element of truth in them. One above all, the fabled Fiddler’s Green, the sailors’ Elysium of perpetually flowing rum casks and willing wenches, no doubt gave comfort to sailors – should they die at sea they would not end as food for fishes but go to a better place. Superstitions, meanwhile, for example the belief that setting sail on a Friday brings bad luck, may have little to back them up, but are still held today.

Life at sea goes at its own pace, and a good yarn-spinner was always a popular member of any crew. Tales such as the legend of Cornish lass Sarah Polgrain, who came back from the grave to enforce her seaman lover’s promise of marriage, would be embroidered at every telling – and the more entertaining the better!

Lurid

details of encounters with mermaids and denizens of the deep held a salty audience spellbound – and guaranteed that the story-teller’s pot of grog seldom ran dry.

Sea serpent, from a sixteenth-century book on Nordic folklore

Sea serpent, from a sixteenth-century book on Nordic folklore.

I

F YOU NEED ME, YOU KNOW WHAT TO DO

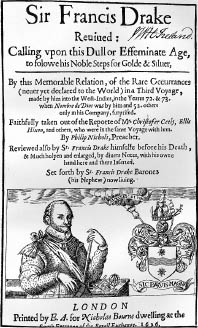

There are legends a-plenty about the Devon-born Elizabethan sea hero Francis Drake. It is said that when he supplied the city of Plymouth with water from the high moor nearby he muttered magic words over a stream and the leat followed him back to the gates of the city. He once whittled on a stick in the harbour and as each shaving fell into the water it was transformed into a fireship which wreaked havoc among the Spanish Armada.

Even Drake’s love life had a supernatural twist. While he was harrying Hispanic ships the lady betrothed to him, fearing him dead, gave her hand to another. As the wedding party entered the church a cannonball fell just short of the building, like a shot across the bows of the bridegroom warning him that Drake was very much alive. Elizabeth Sydenham, the shocked bride, called off the wedding and in due course became Drake’s wife.

On occasion Drake even joins King Arthur to lead the Whist Hunt across the land. Accompanied by spectral hounds with eyes of fire, he rides in a black carriage pulled by four headless horses. They search for no mundane quarry such as fox or deer, but the souls of unbaptised babies.

A more benign legend, that of Drake’s Drum, was celebrated in a famous poem by Henry Newbolt:

Take my drum to England, hang it by the shore

Strike it when your powder’s runnin’ low

If the Dons sight Devon, I’ll quit the port o’ Heaven

An’ drum them up the Channel as we drummed them long ago.

On his voyages around the world Drake carried with him a snare drum emblazoned with his coat of arms. When he lay dying off the coast of Panama in 1596 he expressed the wish that the drum be taken back to Devon, promising that if anyone beat on it when England was in danger he would return and lead her to victory. It is believed that Drake has returned twice, reincarnated once as Admiral Robert Blake and then as Admiral Horatio Nelson.

The drum has been known to sound without the help of human hands when significant national events take place, and there are reports that it was heard at the beginning and end of the First World War.

Drake’s Drum now has pride of place at the Buckland Abbey Maritime Museum in Devon, England.

Drake’s biography, 1626

Drake’s biography, 1626.

P

OLLYWOGS AND BADGER BEARS

Crossing the Line is a ceremony still performed by both naval and merchant ships to celebrate passing through the equator in a north– south direction. Today’s version, however, is a good deal less rowdy than in the Golden Age of Sail. In the early days, the ceremony was a test for the novices on board to see if they could endure the hardships of life at sea. One account from 1708 tells of sailors being hoisted up on the yard and then ducked into the sea up to 12 times. This evolved into a less hazardous version involving a large canvas bath filled with seawater on deck, with a plank across it that could be suddenly withdrawn.

Before the ship actually crossed the line an emissary from the court of

King

Neptune appeared on board. He brought a message for the captain announcing when the king would be arriving and presenting a list of those who were to appear before him.

On the actual day, the pollywogs, those who had not yet obtained their freedom from Neptune, were confined below decks, to be released one by one. King Neptune arrived accompanied by his wife Queen Aphrodite, together with an evil-looking barber, a grim-faced surgeon, fierce-looking guards and various nymphs and badger bears. After parading round the ship, the group convened a court on a platform beside the bath filled with seawater. King Neptune summoned the pollywogs in turn. The barber besmeared their faces with a foul mixture of tar and grease and then scraped it off with a hoop iron ‘razor’. The surgeon administered ‘medicine’ and then these unfortunates were tipped into the bath for a good ducking.

A ship might remain for weeks in the belt of calm that lies close to the equator known as the doldrums. While in this region all aboard suffered from enervating conditions and longed for a breeze. Departure from the doldrums was therefore a time for thanksgiving.

King Neptune, in Ovid’s

King Neptune, in Ovid’sMetamorphoses.

MAKING HEADWAY – progress of a general nature, sometimes hard won.

DERIVATION

: at sea, headway is the ship’s forward movement through the water. Sometimes considerable effort was involved to achieve this, as when a ship tried to tack in a light breeze. The manoeuvre might have to be repeated several times before the sails filled and the cry was heard, ‘She’s making headway.’

REST OR PRESSED?

During the desperate struggle with France from 1793 to 1815 the Royal Navy never had as many men as it needed. At the height of the conflict its authorised strength was up from 45,000 to 145,000. There were a number of ways the navy could man its ships – volunteers, quotas (compelling local authorities to supply a given number of men) and the press gang. The belief persists today that the navy’s seamen consisted almost exclusively of pressed men, taken against their will and subjected to a harsh life at sea, condemning their wives and children to lives of poverty, but this is not so.

The press gang

was

universally loathed, but ordinary folk were generally not at risk. Legally, only those ‘who used the sea’, i.e. experienced mariners, could be pressed. There were some within this category, such as whalers and apprentices, who were issued with a ‘protection’ and were exempt, although in particular periods of manning crisis a ‘hot press’ occurred and these protections were ignored.

One reason for the myth of the press gang’s impact comes down to two words, which in the course of time came to be spelt alike. A ‘prest’ man is a sailor who has received a ‘prest’, a sum of money in advance as an inducement to join the service. A ‘pressed’ man is one who has been taken by force. It is likely that less than half of the navy’s seamen were actually pressed; the majority of them were volunteers.

However, there were abuses of the system and some gangs took men and boys with no previous experience of the sea. The Impress Service maintained gangs in various ports around Britain, organised into 32 districts each commanded by a naval captain. A press gang was usually led by a lieutenant, who bore a warrant signed by the Lords of the Admiralty, and consisted of about ten men.

When they got word that the press was about, sailors often came up with ingenious ways to escape capture, going to ground in the country or disguising themselves as females. A problem with the latter, however, was that their rolling gait and the tar on their hands often gave the game away.

Sometimes the seaports would rebel en masse and pitched battles between the townsfolk and press gangs ensued. Such was the unpopularity of the press that in December 1811 a near riot freed a suspected murderer from police custody as the mob mistakenly believed he was being pressed.

The Royal Navy is often called ‘the Andrew’, from Andrew Miller, a press-gang officer who was so efficient, ruthless and zealous in recruiting seamen that it was alleged he owned the navy.