Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (20 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

Admiral Benbow

Admiral Benbow.

A LOOSE CANNON – someone likely to cause trouble.

DERIVATION

: cannon, which weighed up to three tons each, were mounted on wheels so that they could be quickly run in and out of gunports. They were secured with very strong ropes, but if they got loose in rough seas they would career all over the decks and in a heavy roll a cannon could get up enough momentum to smash through the side of the ship.

J

JOLLIES AND JOHNNIES

‘Jollies’ was the nickname for the trained bands of the city of London, a citizen army from whom the first marines were recruited in 1664 as sea-going soldiers, forming the Duke of Albany’s Regiment of Foot. The origin of ‘Jack/Johnny’ for mariners is harder to trace, but Jack has long been used as a generic term for a working man.

According to Captain Basil Hall, who served in the Napoleonic Wars, the difference between seamen and marines was absolute: ‘No two races of men differ from one another more completely than the “Jollies” and the “Johnnies”. The marines are enlisted for life, or for long periods as in the regular army. The sailors, on the contrary, when their ship is paid off are turned adrift and generally lose all they have learned of good order during the previous three or four years.’

Every warship with more than about ten guns had some kind of marine detachment. On board HMS

Victory

, for example, the marines included 146 officers and men. Marines, who could not be pressed, served as a professional military unit, both afloat and ashore. At sea they were employed to

guard

vital areas of the ship – the powder rooms, magazines, spirit room and the entrances to the officers’ and admiral’s quarters. They gave general assistance to seamen when unskilled heavy labour was required, such as hauling on ropes or turning the capstan, but were not obliged to go aloft. If there was any danger of mutiny, the marines had a paramount role in protecting the officers.

During battle they provided extra manpower to operate guns, and were useful for small-arms fire and close-quarters defence. They also participated in cutting-out expeditions against the enemy.

Seamen had no great inclination to mix with marines, a preference that was deliberately encouraged; they ate and slept separately. There was a certain amount of resentment among the officers of the two services, partly because the marines had a more impressive uniform, but also to do with the fact that mixed parties were generally put under the command of naval officers.

In 1802, largely at the instigation of John Jervis, Earl St Vincent, George III decreed that the soldiers of the sea henceforth would be known as the Royal Marines. Three years later in 1805 some 30,000 marines had been voted by Parliament, and Jervis said of them, ‘If ever the hour of real danger should come to England, they will be found the country’s sheet anchor.’

HE CALL OF NATURE

In sailing ships toilet arrangements were provided in the form of ‘seats of easement’, boxes with a round hole cut in the top. For sailors they were placed at the bow of the ship, at the aftermost extremities of the beakhead, a sensible position as this was essentially downwind and normal wave action would wash out the facility. The term ‘heads’ or ‘head’ originates from this. In British ships, heads is always in the plural to indicate both sides, as seamen were expected to use the lee side, down weather, so that waste would fall direct into the sea. In ships of some other nations they were referred to in the singular.

There were different arrangements for sailors and officers, depending on the size of the ship. Aboard HMS

Victory

, for example, over 650 men had to make do with two benches, each with two holes, placed on either side of the bowsprit. The deck here was open, in the form of a grating, to allow the free sluicing of waves across the area. Petty officers had a seat on either side of the bow. Two small enclosed spaces gave privacy for officers. The admiral, captain and senior officers had their own heads, aft, in the outer part of the great stern galleries.

Toilet paper was not invented in Britain until the late nineteenth century, but officers used newspaper or discarded paper. The seamen made do with scrap fibrous material such as oakum.

By the late eighteenth century there were even flushing toilets aboard some ships – those whose captains could afford them.

GONE BY THE BOARD – gone for good.

DERIVATION

: the side of a ship is known as a board, and if a mast, for example, was carried away it was said to have gone by the board.

I

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

There aren’t many letters from eighteenth-century seamen in existence – mainly because most Jack Tars were illiterate, but also because letters of ordinary people were not often saved for posterity.

The few that have survived offer poignant insights into those times. Here are excerpts from two. The first is from a pressed man in HMS

Tiger

, writing home to his wife after the capture of a Spanish port.

My dear Life:

When I left you, heaven knows it was with an aching heart to be hauled from you by a gang of ruffians but however I soon overcame that when I found that we were about to go in earnest to right my native country and found a parcel of impudent Spaniards… and God knows, my heart, I have longed for this for years to cut off some of their ears, and was in hopes I should have sent you one for a sample now. But our good admiral, God bless him, was too merciful. We have taken Porto Bello with such courage and bravery that I never saw before – and for my own part, my heart was raised to the clouds and I would have scaled the Moon had a Spaniard been there to come at him… My dear, I am well, getting money, wages secure, and all Revenge on my Enemies, fighting for my king and country.

The next is from a young man who visited a friend in his ship who had joined the navy previously.

I spent the evening with him very pleasantly, and the sailors of his mess, as is their manner in men-of-war, procured us plenty of wine and everything that could be got to make a stranger comfortable; when morning came and I should go ashore, I felt reluctant to part with my friend, and instead of doing so I volunteered to serve His Majesty…

HE BENEFITS OF CLARET

Officers often recorded their wine consumption in terms of bottles, rather than glasses. One of the Royal Navy’s most colourful characters, Thomas Cochrane, recalled trying to avoid getting too drunk during his youthful years in the navy by pouring some of his wine down his sleeve. He was discovered and narrowly escaped the standard punishment of having to drink a whole bottle himself. French wine was popular, often from captures, and claret was said to ‘assist the memory, give fluency to speech and animate the mind with real gaiety to enliven conversation’.

An eighteenth-century poster calling for volunteers to join one of His Majesty’s ships bound for the North American station read:

Who would enter for a small craft whilst the

Leander

, the finest and fastest sailing frigate in the world, with a good spar deck overhead to keep you dry, warm and comfortable, and a lower deck like a barn where you may play at leap-frog after the hammocks are hung up, has room for one hundred active smart seamen and a dozen stout lads for royal yard men? This wacking double-banked frigate is fitting out… to be a flagship on the fine, healthy, full-bellied North American station, where you may get a bushel of potatoes for a shilling, a codfish for a biscuit, and a glass of boatswain’s grog for twopence. The

officers

’ cabins are building on the main deck on purpose to give every tar a double berth below. Lots of leave on shore! Dancing and fiddling on board! And 4 pounds of tobacco served every month! A few strapping fellows who would eat an enemy alive wanted for the Admiral’s barge. Every good man is almost certain of being made a warrant officer, or getting a snug berth in the dockyard… God save the King, the

Leander

and a full-bellied station!

A CLEAN SLATE – a fresh start.

DERIVATION

: during a voyage all the current sailing orders were chalked up on a slate by a quartermaster, as instructed by the officer of the watch. Variations in the course to steer, the set of the sails and other important information were noted or amended. The slate was wiped clean at the beginning of a new watch or when the ship was safely at anchor in harbour.

J

JUST ONE NIGHT

On 19 March 1801 Captain Richard Keats assumed command of HMS

Superb

. For the next four years and five months, until he put her into dockyard hands for repair on 22 August 1805, he would spend only one night out of his ship. While this probably is a record, service in the Royal Navy often meant long periods of time away at sea: Nelson was on blockade duty for two years and three months without setting foot off HMS

Victory

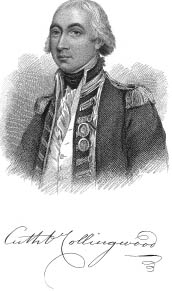

, and Collingwood once kept at sea for 22 continuous months, never dropping anchor. After Nelson’s death at Trafalgar Collingwood spent the next five years almost perpetually at sea. In 1809 he wrote to his wife, ‘I shall very soon enter my fiftieth year of service, and in that time I have almost forgot when I was on shore.’ Worn out from tireless devotion to duty he died at sea the next year, four days after finally being recalled home.