Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (6 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

EAMAN TO SAMURAI

In Japan William Adams became known as ‘

Miura Anjin

’, the pilot of Miura, after the estate he was given in recognition of his services to his adopted country. An English navigator, Adams served under Francis Drake and was later recruited by the Dutch for their trading voyages to the East Indies.

In April 1600, after more than 19 gruelling months at sea, the merchantman

Liefde

anchored off Kyushu in Japan. Adams was among what remained of the crew, just 20 sick and dying men. Initially believed to be pirates, they were seized and incarcerated. Adams was nearly executed, but as the fittest of the prisoners he was brought to Osaka for questioning. A powerful feudal lord who would later become

shogun

took a liking to

him

, eventually making him a diplomatic and trade adviser and bestowing great privileges on him.

Adams supervised the building of several Western-style ships for the shogun, who conferred the rank and authority of a samurai on him. Although he had a wife and children in England, Adams married a Japanese woman and had another family with her, but he was forbidden to leave Japan.

In 1611 a letter from Adams was received at the London offices of the East India Company. As a result they began sending ships to the Far East to trade with Japan. Adams facilitated similar arrangements with the Netherlands and personally became involved in Japan’s Red Seal trade, in which merchant sailing vessels conducted business with Southeast Asian ports under the authority of a red seal permit issued by the shogun.

One of the most influential foreigners during Japan’s first period of opening to the West, William Adams died in Japan on 16 May 1620, aged 56. His life story inspired the character of John Blackthorne in James Clavell’s

Shogun

.

Red Seal ship

Red Seal ship.

‘M

Y FIN

’

Following his injury from a musket-ball at Tenerife in 1794, Nelson’s right arm was amputated high up near the shoulder. The operation was performed without anaesthesia, and it is unlikely that he was given rum to dull the pain as alcohol was said to interfere with the clotting of the blood. Within a short time of the surgery he was issuing orders to his captains. The wound, however, took many months to heal as one of the ligatures used during the operation, which normally fell out after a few weeks, remained in the wound, causing continuing infection and intense pain.

The surgeons who performed the amputation and the doctors and apothecaries who cared for Nelson received special payment; he was reimbursed £135

1s. 0d

. for his medical expenses.

Nelson sometimes experienced the sensation of a phantom arm. He nicknamed the stump his ‘fin’, and it was said that it twitched if he was agitated or angry. Officers would then warn: ‘The admiral is working his fin, do not cross his hawse.’

Nelson sometimes joked about his affliction. On his arrival in Great Yarmouth in November 1800 the landlady of the Wrestlers Arms asked permission to rename her pub the ‘Nelson Arms’ in his honour. ‘That would be absurd, seeing I have but one,’ he replied. And when, at a levée at St James Palace, George III referred to his having lost his right arm, Nelson came back swiftly, ‘But not my right hand,’ and, turning to one of his companions, told the king, ‘I have the honour of presenting Captain Berry.’

OME PASSENGER

…

Shortly after the Battle of Waterloo Napoleon Bonaparte surrendered – not to Wellington but to the captain of the ship that had dogged his steps for more than 20

years

, HMS

Bellerophon

– ‘Billy Ruffian’

to

her crew. The ship sailed for England and dropped anchor at Torbay on 24 July 1815. Every effort was made to keep the famous man’s presence a secret, and no one was allowed to come on board. However, a sailor dropped into the water a black glass bottle which was retrieved by some young boys in a small boat nearby. Inside the bottle was a rolled piece of paper with the electrifying message, ‘We have Bonaparte on board!’

Once the word spread, the vessel was quickly surrounded by sightseers in anything that could float. Bonaparte even appeared on deck to greet the crowds. The British government was worried that the emperor might escape before they could work out what to do with him, so

Bellerophon

was hastily ordered to weigh anchor and sail to Plymouth, with its more secure harbour.

Needless to say people thronged there; at the height of the madness 10,000 people boarded 1,000 boats in an attempt to get a view of the most famous man in the world. Several even drowned in the frenzy.

The crew of

Bellerophon

hung notices over the ship’s side as to their famous guest’s movements: ‘In cabin with Captain Maitland’, ‘Writing with his officers’…

Among the crowds were large numbers of pretty young women, naval officers, fashionably dressed ladies, red-coated army officers and smartly attired gentlemen. The men took off their hats respectfully when Napoleon showed himself, as he did every evening around 6 p.m. He commented on the beauty of the young ladies and appeared astonished by the size of the crowds.

On 7 August Napoleon was transferred to HMS

Northumberland

for exile in St Helena, where he died in 1821.

Bonaparte was proclaimed First Consul for Life in 1802. He crowned himself Emperor Napoleon I in 1804

Bonaparte was proclaimed First Consul for Life in 1802. He crowned himself Emperor Napoleon I in 1804.

SWINGING THE LEAD – skiving to avoid work.

DERIVATION

: the depth of water under a vessel was measured by lowering a lead weight on the end of a rope over the side of a ship. It was necessary to twirl the line and shoot it ahead so that by the time the lead had sunk to the bottom the ship’s headway would have brought the line perpendicular and the correct depth could be seen. Some seamen would make a great display of twirling the lead around their heads, pretending to be active rather than doing the job properly.

‘B

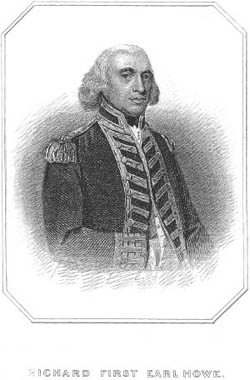

‘BLACK DICK’ TO THE RESCUE

Richard Howe was one of the larger-than-life figures in British maritime history. He spent 60 years as a professional sea officer, serving with great distinction in many of the famous fleet actions of the age. Howe was officially Lord Richard Howe of Langar Hall, but to the sailors of the fleet he was always just ‘Black Dick’. There have been a number of explanations offered for this, his swarthy complexion being one. The fact that he was said never to smile unless a battle was about to begin may also have earned him his nickname!

On 16 April 1797, a mutiny began at Spithead, the chief naval anchorage near Portsmouth. Sixteen ships in the Channel Fleet raised the red flag of insurrection: their principal demands were for a rise in pay (which had not been changed for 150 years), a more equitable distribution of prize money and better victuals. The mutineers elected delegates from each ship to represent them.

When negotiations broke down between the two sides, George III personally requested Howe, who was held in very high regard by British seamen, to go down and talk to the mutineers. Although over 70 and suffering from gout and other ailments, he agreed. When First Lord Spencer asked the admiral who he wished to accompany him he replied simply, ‘Lady Howe.’

They set out on 10 May on a wild and stormy night and arrived at Portsmouth the following morning. Howe left his wife at the governor’s house and immediately set out by barge for Spithead. He came alongside HMS

Royal George

, the headquarters of the insurrection, and despite his

infirmities

he rejected all offers to help him come aboard and clambered up unaided. He called the ship’s company to the quarterdeck and started to talk to them man to man, neither reproaching their conduct nor standing on his dignity. Several hours later he went to HMS

Queen Charlotte

. For three days he went from ship to ship – talking, listening, heaving his rheumaticky knees and gouty feet up and down ladders until he was so tired he had to be lifted in and out of his boat. But by the end he had achieved reconciliation on both sides, with a Royal pardon for all the mutineers, a reassignment of some of the most unpopular officers and a pay rise and better victualling for the seamen.

On 15 May there was a grand celebration in Portsmouth, and the mutineers’ delegates marched in procession up to the governor’s house accompanied by bands playing ‘God Save the King’ and ‘Rule, Britannia’. The delegates were invited inside for refreshments, then appeared on the balcony with the Howes to huzzahs from the multitude, after which they set out together for the anchorage. On board

Royal George

Howe was given three cheers and the red flag of mutiny was pulled down; the other ships quickly followed. Later that day Lord and Lady Howe hosted a special meal for the delegates before they returned to their ships and reported for duty.

Nelson called Howe ‘our great master in tactics and bravery

Nelson called Howe ‘our great master in tactics and bravery’.

A

WOMAN’S TEARS SAVED

VICTORY

England’s most iconic ship already had a long and proud history before her most famous role as Nelson’s flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Although she was well over 40 years old, considerably past the normal life span of a ship of the line, she went on to further service in the Baltic and other areas. Her career as a fighting ship effectively ended in 1812. She was 47 years old, the same age Nelson had been when he died.

In 1831 she was listed for disposal, but when the First Sea Lord Thomas Hardy told his wife that he had just signed an order for this, Lady Hardy is said to have burst into tears and sent him straight back to the Admiralty to rescind the order. Curiously, the page of the duty log containing the orders for that day is missing.

Victory

was permanently saved for posterity in the 1920s by a national appeal led by the Society of Nautical Research. To this day she is manned by officers and ratings of the Royal Navy and has now seen two and a half centuries of service, proudly fulfilling a dual role as flagship of the commander-in-chief naval home command and as a living museum of the Georgian navy.