Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (7 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

Victory.

O

F UMBRELLAS AND URCHINS

Jonas Hanway has two claims to fame – for introducing the umbrella to England and encouraging a life at sea for many thousands of men and boys.

Merchant, philanthropist and social reformer, Hanway travelled extensively. In Persia he was taken with a silk parasol and brought one back to England. It was light green outside, pink inside. Its carved handle had a joint in the middle so that it could fold and go into his coat pocket. Hanway was ridiculed for many years by hackney coachmen who thought it would cause them to lose income. Hanway stubbornly carried an umbrella through London for three decades and lived to see it become the standard accoutrement for a gentleman, even being called a ‘Hanway’.

In 1756 Britain was facing a severe shortage of men in the navy as she found herself embarked on another war. Concerned about the manning crisis, Hanway called a meeting of London merchants and other interested parties at the ‘King’s Arms’ on 25 June. He proposed that they set up an organisation that would provide practical encouragement to young men to volunteer for service at sea. He also saw this would be a way for the street urchins of London to escape their miserable conditions. Thus the world’s first seafaring charity, the Marine Society, was born.

It offered sponsorship to ‘all stout lads and boys, who incline to go on board his Majesty’s ships, with a view to learn the duty of a seaman, and are, upon examination, approved by the Marine Society, [they] shall be handsomely clothed and provided with bedding, and… borne down to the ports… with all proper encouragement’.

By 1763 the Marine Society had recruited over 10,000 men and boys. In 1786 it commissioned the world’s first pre-sea training ship, the sloop

Beatty

. Admiral Nelson became a trustee of the charity, and at the time of the Battle of Trafalgar 15 per cent of the navy was being supplied, trained and equipped by the Marine Society.

Today, a little over 250 years after Hanway’s meeting in the ‘King’s Arms’, the Marine Society, now merged with the Sea Cadets, continues to serve seafarers.

Marine Society boardroom, 1756

Marine Society boardroom, 1756.

BOW AND SCRAPE – being excessively servile.

DERIVATION

: an officer’s cocked hat was known as a ‘scraper’ after its similarity to the wooden utensil of the same name used by the ship’s cook. When greeting a superior officer it was customary for the junior officer to remove his headgear and bow.

O

OOPS

…

HMS

Mutine

won lasting fame for bringing news of Nelson’s great victory at the Battle of the Nile. In 1842

Mutine

was sold and sailed halfway around the world to Tasmania, Australia, where she became a government powder hulk and was moored in the harbour at Hobart until 1902. In tribute to her illustrious past Tasmanian officials respectfully decked her out with festive flags each year on the anniversary of the battle. However, in the Royal Navy only one ship carries a particular name at one point in time and when a vessel is lost, or sold out of service, the name is freed to be used by another. The

Mutine

in the Antipodes had not been at the Nile; she was in fact two namesakes down the line.

HE SWEDISH KNIGHT

’

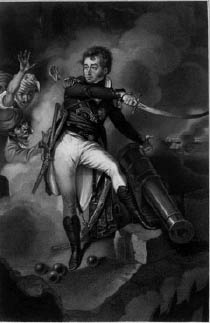

Sir Sidney Smith was one of the most colourful characters of his time – vivacious, quick, daring and mercurial. He entered the Royal Navy in 1777 and soon distinguished himself in battle. He was made post captain at the age of 18. Between 1789 and 1791 he was an adviser to the king of Sweden in the maritime war with Russia. King Gustavus conferred an order of knighthood upon Smith, earning him the mocking nickname ‘the Swedish knight’ from his contemporaries, most of whom took against his flamboyance.

In 1799 Smith was given charge of the Turkish naval and military strength assembling to attack a French invasion force. He took command of two British warships at Alexandria, and when he heard that Bonaparte had stormed Jaffa on his way to Syria he quickly made his way to the walled city of Acre that stood athwart Napoleon’s route for his advance into India.

There

he put 800 seamen and marines ashore and mounted ships’ guns on the ramparts. Over the next six weeks his courage and determination inspired the Turkish defenders against overwhelming odds. Napoleon gave up his ambitions and the siege was raised on 20 May.

A grateful Britain gave Smith a pension of £1,000 a year, along with the thanks of both houses of parliament. The sultan of Turkey presented him with the

chelengk

, the plume of triumph, which he delighted in wearing. The magnitude of the defeat for the French was such that years later in lonely exile Napoleon said of Smith: ‘That man made me miss my destiny.’

After Acre, however, Smith never achieved such accolades again. Although highly intelligent, his career was constrained by a reputation for impulsiveness and unconventionality. One admiral found him ‘as gay and thoughtless as ever’, and Wellington called him ‘a mere vaporiser’.

Finally, in December 1815, Smith was awarded a British knighthood – he was no longer just ‘the Swedish knight’. He attained the rank of admiral in 1821 and in his later years campaigned vigorously for the release of Christian slaves from captivity in North Africa.

Sir William Sidney Smith depicted at the Battle of Acre, his greatest triumph. The painting is by John Eckstein, who also recorded the Royal Navy’s incredible achievement in fortifying Diamond Rock in 1804

Sir William Sidney Smith depicted at the Battle of Acre, his greatest triumph. The painting is by John Eckstein, who also recorded the Royal Navy’s incredible achievement in fortifying Diamond Rock in 1804.

MAINSTAY – someone of great support and help.

DERIVATION

: in a sailing ship a stay is part of the standing rigging that supports a mast. Stays take their name from the mast they support; a mainstay is thus a crucial component on any vessel.

HALK AND CHEESE

Louis Infernet and Jean Lucas were arguably the two most courageous French captains at the Battle of Trafalgar, but they could not have been more different in appearance.

Infernet stood 1.8 m tall and was built like a prize fighter. He spoke in a rough Provençal dialect; one of his colleagues said of him, ‘

Infernet parle mal, mais il se bat très bien

’ – Infernet speaks badly, but he fights damn well. Commanding

Intrépide

, he fought one of the most gallant actions of the battle, at one point under fire from four or five British warships simultaneously.

Lucas, on the other hand, slightly built and standing under 1.5 m tall, was the smallest officer in the French fleet. His ship

Redoutable

became sandwiched between HMS

Victory

and HMS

Temeraire

and endured a relentless pounding from their broadsides. Lucas and his crew fought heroically as decks were torn open, guns shattered. When he eventually surrendered just one mast remained upright. Their butcher’s bill was horrendous – 88 per cent of her crew were either killed or injured.

EA-GOING SYMBOL OF PRIDE

Bluenose

was a deep-sea fishing schooner that won a special place in the hearts of all Canadians during the depths of the Great Depression, an admiration that continues to this day. As one newspaper observed: ‘Her name is a household word. She has knit Canada together.’

It all began with a small item in the sports page of a New York paper in 1919 announcing that the America’s Cup race had been postponed because of a blow that would barely tickle the sails of a saltbank schooner. The men of the fishing fleets of Gloucester in Massachusetts and Lunenburg in Nova Scotia were outspoken in their scorn.

Competition between the two communities had always been fierce and here was the perfect excuse to have a race between real working schooners. In 1920 the International Fishermen’s Race was organised, and that year the schooner

Esperanto

out of Gloucester defeated the

Delewana

of Lunenburg and took the trophy to New England. The cousins in the north were not

going

to take this sitting down, however, and in the following spring a challenger bearing the name

Bluenose

was launched, a ‘Bluenose’ being a resident of Nova Scotia.

She was constructed by traditional methods using local timbers, and had, of course, the sturdy build of a working schooner. Her lines were sweet, however, and she was fast, achieving her best speed under a strong blow beating to windward. In 1921 she raced twice against

Elsie

in the waters off Halifax.

Bluenose

took both races with a good margin and even reduced sail to match the American vessel during one race when her opponent temporarily got into difficulty.

Bluenose

was a ‘witch on the wind’ and nothing could catch her.

Undefeated in all the International Fishermen’s trophy series held between 1921 and 1938, she became an enduring symbol of Canada’s maritime spirit. In 1929 the Canadian Postal Service issued a distinctive blue stamp to honour the vessel’s racing record, and in 1937 she appeared in full sail on the Canadian dime.

Bluenose

’s fame was not confined to North America and Canada. She officially represented her country at the World’s Fair in 1933 and the Silver Jubilee of King George in 1935.

Sadly, she met her demise in 1946 when she foundered near Haiti, some say as the result of a voodoo curse. But her name lives on. The reverse side of the Canadian dime still proudly bears an image of the schooner. Meanwhile

Bluenose II

, a daughter ship launched from the same shipyard and built by many of the same men who worked on the original

Bluenose

, carries on the tradition of sailing ambassador for Canada.

The Bluenose, Canada’s favourite stamp. In 2001 a Bluenose first day cover sold for nearly C$4000

The Bluenose, Canada’s favourite stamp. In 2001 a Bluenose first day cover sold for nearly C$4000.

N

OT A MAN LOST

William Bligh has not had a good press, and is thought of as one of the most tyrannical and cruel captains ever to command a ship. This largely false accusation has overshadowed his achievement of one of the most remarkable feats of seamanship and survival of all time, his near 6,400-km open-boat voyage across the vast and empty western Pacific with scant provisions and only very basic navigation equipment.

On 28 April 1789 there was a mutiny aboard Bligh’s ship HMS

Bounty

. Fletcher Christian and the master-at-arms burst into Bligh’s cabin. They had come to the end of their tether after his continuing vicious insults and vowed to cast him and his supporters adrift, thereby condemning them to a lingering death.