Stonehenge a New Understanding (42 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

Some people think that this bluestone Cunnington took from Boles Barrow must be the same stone that’s now housed in Salisbury Museum, although that stone weighs 611 kilograms, much heavier than anything mentioned by Cunnington, and came to the museum not from Cunnington’s garden but from one nearby at Heytesbury House, in 1923. Various scholars have tried to unpick the chain of historical events—none more thoroughly than Mike Pitts, who is convinced that the two stones are not one and the same.

28

Yet the matter is still problematic. Mike has also had a good look at what survives of Boles Barrow; it has been severely damaged by human and animal activity, and was definitely reused as a cemetery in periods more recent than the Neolithic. There’s no guarantee that the Boles Barrow bluestone was part of the Early Neolithic construction; it could have been brought there later in the barrow’s period of use. Even if it was part of the first construction, Mike argues that Cunnington could easily have mistaken another type of igneous rock for a bluestone. Both Colin and I, along with Richard Atkinson before us, have been guilty of such a mistake until corrected by geological experts. The problem of the bluestones is that everybody

wants

to find them, but only identifications by geologists can be relied on.

Even with Mike Pitts’s caveats about Cunnington’s Boles Barrow bluestone, there is still a chance that bluestones as well as some of the preselite axes were present on Salisbury Plain before 3000 BC. However, I don’t think we have to resort to the glacial hypothesis to explain them. As I’ve argued earlier, we live in a world where the pragmatic and the cost-effective are often the guiding criteria for our actions, but this is a

culturally specific view of the world. To understand the meaning and practices of stone-moving, we have to fight an innate prejudice that often makes us try to explain prehistoric activities in terms of what we see as common sense.

This is hard because most of the time we don’t realize we’re doing it. Working in non-Western societies provides the best opportunity to get one’s eyes opened to a myriad of other possible ways of doing things. During fieldwork with Ramilisonina, we learned from the Tandroy people of southern Madagascar that they prefer to import their standing stones from sixty miles away rather than use what looked to me like perfectly acceptable outcrops of stone just twenty miles away.

29

The nearer quarries are often used but they are not the “best.” There is nothing more important to Tandroy tomb builders than showing off—paying extra to get hold of a more inaccessible stone is part of social competition.

These megaliths have to be hauled in wooden carts over difficult terrain from this distant source at a place called Trañoroa (two houses). There are no paved roads, and journeys are slow and arduous across a landscape so rocky that even a Land Rover struggles, yet people transport standing stones across it by ox power alone. Although the Trañoroa stones are of a softer rock than the nearer stone, and are therefore difficult to transport, when properly bedded with shock-absorbing materials, they do survive the journey intact. The Tandroy say that they like the particular color of the Trañoroa stones, and that they can be cut into pleasingly rectangular monoliths. For the Tandroy, who live in a precarious environment, often on the edge of famine, commemorating the ancestors is the most important aspect of their lives: The goal of life is to honor the dead through monument-building, in which no expense is spared. Very little of what they do in their religious and funerary observances is practical in our terms.

Closer to home, we are all well aware that stones can take on powerful spiritual symbolism, as is shown by current mystical notions surrounding Stonehenge itself. The Stone of Scone is a good example of a stone with “meaning.” Now safely under lock and key with the other treasures of Scottish kingship in Edinburgh Castle, it has had a very eventful life. Originally the throne of Scottish kings, it was captured and brought to Westminster Abbey by Edward I in 1296; during the twentieth

century, the stone was stolen from London, eventually recovered, and is now back where it started.

30

The Stone of Destiny, at Tara in Ireland, is another example of a monolith with a special history relating to power and kingship.

31

Fewer people have heard of the London Stone, located in a basement on Cannon Street; its early history is unknown but it has been a London landmark since at least 1198, and is the location where laws were once passed and oaths sworn.

32

Later I’ll explore what I think may have been the reasons for moving stones from west Wales to Salisbury Plain—and why I think it most likely that they were dragged overland, with as few river crossings as possible. For the moment it’s worth pointing out two flaws in the logic of the argument for the Stonehenge bluestones having been fetched from a hypothetical location in Somerset.

- At Stanton Drew, in north Somerset, there is a very impressive group of stone circles and settings, just twenty miles north of Glastonbury.

33

The stones of these circles come from a variety of outcrops in the region. There is not a single bluestone among them. The glacial-erratics hypothesis places the source of the Stonehenge bluestones in exactly this area. If bluestones were present in the area, why did the builders of these stone circles

not

use them, even though other builders were coming all the way from Wiltshire especially to get them? - Glastonbury, Somerset, and the Bristol region are much further from Stonehenge than the sarsen fields of the Marlborough Downs. If proximity of materials was an overriding concern of the Neolithic builders, why go all the way to Somerset to get any stones at all? It makes no sense for the builders of the first stone circle at Stonehenge to have ignored local sarsens less than twenty miles away (or the even closer Cuckoo Stone and Tor Stone),to go sixty miles in search of building material.

At this point, most readers will have worked out for themselves a convincing answer to what was behind all this: There has to have been something special about bluestones. These are the stones the Neolithic builders of Stonehenge

wanted

to use, and they were prepared to go to

great lengths to get hold of them. It wasn’t a matter of erecting any old stone that came to hand—it had to be bluestones.

There’s plenty of evidence that Neolithic Britain was a place of busy trade routes, with people and objects traveling long distances. Back in the 1970s, archaeologists argued about the movement of stone axes in Neolithic Britain. Axes of Cumbrian, Welsh, and Cornish stone turn up all over the country, including Wessex, and some thought this is because Neolithic people exploited local deposits of glacial erratics within southern England. Then archaeologists started finding the actual quarries where the axes had been manufactured.

34

These axes didn’t all come from glacial erratics, but from quarries in the mountains from which they were dispersed all over the country.

At the same time, archaeologists discovered that some Neolithic pottery was also being moved more than a hundred miles from the sources of the clay with which it was made. Early Neolithic Britain has turned out to be a pretty sociable place, if sporadically violent. Recent excavations of causewayed enclosures have shown that all kinds of items—from axes and flint to pots and cattle—were moved surprisingly long distances.

35

While there’s no denying that some axes might have been made locally from glacial erratics, there was a thriving long-distance network, which shows that the Neolithic inhabitants of Wessex, for example, engaged with other communities in distant regions of the country.

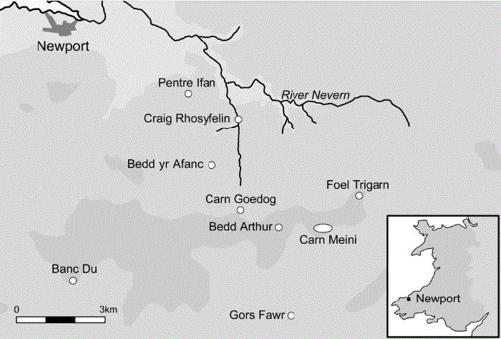

Tim Darvill and Geoff Wainwright went back to the source of the bluestones, hoping to dispel the glacial hypothesis once and for all. Just as previous archaeologists had found Neolithic quarries for the axes, perhaps they could find one or more quarries in Preseli for the spotted dolerite monoliths. In 2001 they started a project, the Strumble-Preseli Ancient Communities and Environment Study (SPACES), to begin the search for the bluestone quarries.

36

Carn Goedog, the outcrop with the closest chemical signature to the Stonehenge spotted dolerites, has been used as a quarry in more recent times so they knew it would be difficult to find the ephemeral traces of Neolithic quarrying beneath more modern debris. They selected Carn Menyn as the most promising location at which to start. Here, around the outcrops of dolerite, there are possible prehistoric remains, whereas the area around Carn Goedog was thought to be empty of such sites.

On a cold and wet day, Geoff took me to see what he and Tim had found so far. One of the outcrops forms a spectacular group of natural monoliths, and Geoff explained that it would require very little effort to detach these pillars from the living rock. They could then be maneuvered downhill and taken southward along the Cleddau river and on to Milford Haven. At the bottom of the slope below Carn Menyn, we inspected a Stonehenge-sized monolith that had cracked in two after its edges had been roughly shaped. Could this be a quarried stone that had broken and been abandoned? At the top of the outcrop is a small, flat area surrounded by a low stone wall. Geoff and Tim needed to investigate whether this might be a Neolithic enclosure built by the quarry workers and, in 2005, they carried out a small excavation. The acidic soils of Preseli are not kind to archaeological remains, however, and there were no finds to give any indication of the period in which this stone wall was built.

Preseli is rich in Neolithic monuments. Bedd yr Afanc is a long cairn containing a gallery grave,

s

excavated in 1939 but containing few finds.

37

On the western end of Carn Menyn itself, there’s a stone cairn whose central capstone suggests that this, too, is a passage grave. Three large cairns on the nearby hilltop of Foel Trigarn (or Drygarn) were probably built in the Early Bronze Age, but a Neolithic date cannot be ruled out. To the north is the well-known portal dolmen of Pentre Ifan, from which a flint arrowhead and fragments of carinated bowl pottery were excavated in 1936–37 and 1958–59.

38

t

In 2005, Tim and Geoff excavated a small trench across the bank and ditch of a causewayed enclosure at Banc Du, and found that the enclosure bank had a stone-walled outer face with timber posts behind. Charcoal from its ditch dated to around 3550 BC.

39

Geoff and Tim have also been finding evidence of prehistoric rock art in the area. This takes the form of cup-shaped marks ground into stones, with examples from the springheads below Carn Menyn and from St David’s Head, where the Preseli Hills meet the sea. Of course, such remains are impossible to date beyond being loosely Neolithic or Early Bronze Age. It is generally thought that cup-marked stones are most likely to be Neolithic in date.

As well as standing stones, set up either singly or in pairs, there are also six stone circles in Preseli, only one of which has been excavated and whose dates we can therefore only guess at, although small circles such as these sometimes date as late as the Bronze Age; the only circle excavated—Meini Gwyr in 1938—produced only a few shards of Middle Bronze Age pottery.

40

The stones of these six circles are rather stumpy, nothing like the taller bluestones of Stonehenge, some of which stand as high as two meters.

The stone circle of Gors Fawr, south of Carn Menyn, is an egg-shaped arrangement of sixteen widely spaced monoliths, eight of which are of spotted dolerite. Tim and Geoff’s geophysical survey did not reveal any features beneath it. They were luckier with the circle of Meini Gwyr, set within a circular bank. Here the geophysics showed that there had never been a ditch to go with the bank. The survey results also picked out a series of anomalies underneath the bank that may be the holes for an outer ring of standing stones.

Another circle is Bedd Arthur, a sub-rectangular arrangement of bluestones that Geoff compares with the bluestone oval in the center of Stonehenge, although it is longer and thinner in shape than the Stonehenge setting. The thirteen stones are backed by a low bank and surround a leveled area. Other archaeologists have previously considered the stones at Bedd Arthur to be part of a walled enclosure of the Bronze Age or later, rather than a true stone circle.

There is no denying the richness of Neolithic remains from Preseli, but incontrovertible evidence for bluestone quarrying has eluded the SPACES team. Frustratingly, the stone-walled enclosure on Carn Menyn could be any date, as could the several pillar stones seemingly broken in transit. Bluestones have been used as gateposts and other structures for centuries, and it’s impossible to say whether any of the worked pillar stones are prehistoric. That said, the shapes and sizes of the abandoned

pillar stones recorded by Geoff and Tim compare well with the smaller bluestones at Stonehenge.

In the Preseli Hills there are several outcrops of dolerite and rhyolite from which the Stonehenge bluestones derive. This landscape also contains Neolithic tombs and other prehistoric monuments.