Stonehenge a New Understanding (45 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

I doubt whether archaeologists will ever be able to prove beyond doubt that this was the route taken by the bluestone movers. If the source of the Altar Stone and the other sandstone monoliths at Stonehenge can be found (these could be from the Brecon Beacons or from west Wales), it may just help to confirm or negate this theory. Finding the sources of all the other types of bluestone—rhyolitic ignimbrite (tuff), calcareous ash, volcanic ash, and altered volcanic ash, unspotted dolerite, and one other type of rhyolite—will also help to identify whether all or just some of the stones were taken from the northern edges of Preseli, and which route was taken. There is much for archaeologists and geologists to look for in the years to come.

17

__________

The Stonehenge sarsens never attract as much interest as the bluestones, and discussions about their origin have been much less heated. The sarsens really ought to be the center of attention because they’re so big. The extraction, transport, and shaping of these giants would have been an engineering project on a scale never before seen in prehistoric Britain. Sarsen occurs naturally in Kent as well as in central England, but it is best known from the deposits on the Marlborough Downs in north Wiltshire. Even today, fields around Fyfield Down and Piggledean are littered with large gray lumps of sarsen, and it’s easy to see how they acquired the name of graywethers, or sheep. They are scattered in stony flocks across the grasslands.

Since John Aubrey’s time, almost four hundred years ago, these downs have been thought to be the source of the Stonehenge sarsens. Yet none of the stones lying around today is anywhere near as big as those used for the Stonehenge uprights. The largest uprights are those of the great trilithon; the stone still standing (Stone 56) is more than nine meters tall and the fallen one (Stone 55) is ten meters long. Each of these must weigh around 35 tons and, together with their lintel, once formed the largest single megalithic structure in Britain.

The uprights of the sarsen circle are generally around five meters tall and each weighs around 20 tons. The squared-off appearance of the stones above ground (they look to me like a set of dominoes) belies their irregular bases: The buried parts of the stones, as Hawley discovered, are often irregular in shape.

1

The builders were keen to present an image of

symmetry and rectangularity above ground, so any awkwardly shaped ends are underground. The problem with this strategy is that it compromised the stability of many of the uprights, and is why so many have fallen down or have had to be restored in the twentieth century. During our last trip to Stonehenge, Ramilisonina noticed immediately—drawing on his own knowledge of stone-erecting—that many of the fallen sarsens have toppled because of their inadequate bottom ends.

The lintels are much smaller than the uprights. All five of the trilithon lintels survive, three of them still in position on the tall uprights and two on the ground nearby. The lintel that once lay across the tops of Stones 59 and 60 (the north trilithon) has been broken into three lumps that no longer fit together; it has evidently been chipped and quarried in more recent centuries. The trilithon lintels are five meters to six meters long, and most of the still-complete examples of the surviving seven lintels in the outer circle of sarsens are each just over three meters in length.

In all, the builders of Stonehenge had to look for sarsen stone to create ten trilithon uprights, five trilithon lintels, thirty circle uprights, thirty circle lintels, four Station Stones and three Slaughter Stones, a total of eighty-two stones. The Heel Stone may be a naturally occurring sarsen, and therefore already present when building work began, and the three empty stoneholes between it and the Slaughter Stone could have once been filled by an earlier arrangement of the Heel Stone and the two accompaniments to the Slaughter Stone. If two of the three Slaughter Stones were already on site when the major building work began, in an earlier alignment with the Heel Stone, that would have made eighty sarsens to go out and find—about the same number as the bluestones.

Weathered natural sarsens develop a thick, hard crust that makes this rock extremely difficult to shape. Some sarsens have an iron-hard quartzitic surface that is resistant to stone tools, even in the hands of skilled masons. This quartzitic sarsen was only of interest to Stonehenge’s builders in its pebble and boulder form because these tough rocks could be used as hammerstones and mauls. Mauls were boulders that could be used to pound by hand, but were probably more efficient if suspended from a rope and swung at the sarsen block. By hitting it at the right angle, the stone worker could detach a large flake, thereby gradually

shaping the block into the desired form. The softest sarsen has a sugary, crystalline texture, though there is much variation in texture and hardness.

2

It’s highly likely that the sarsens sought by the Stonehenge builders were buried below ground, because buried stone surfaces are crust-free and relatively easy to flake and pound. While digging test pits along the Kennet valley at Avebury, John Evans found buried sarsens.

3

They probably survive all over that part of north Wiltshire. One just has to know where to look for them.

As researchers realized many years ago, the current distribution of above-ground sarsens has only the weakest link to their former distribution, thanks to millennia of quarrying and removal.

4

The limits of today’s distributions are like high-tide marks; a human wave of stone-removers has taken everything from below this line. So where can we look to find the Neolithic sarsen quarries?

Richard Atkinson suggested that Avebury was a marshaling area for the stones: He thought that the larger slabs now at Stonehenge were previously erected there, although no one knows exactly when the stone circles at Avebury were constructed.

5

Today, most of Avebury’s original standing stones are missing; many were broken up in historical times, but it’s possible that others were taken down much earlier to be moved to Stonehenge. Atkinson reckoned that here, near Avebury, was the lowest point on the River Kennet and that the large sarsens could have been simply dragged across a shallow ford; crossing this river any further downstream to the east would have required the construction of a substantial wooden causeway. Atkinson also recognized that the symbolism of dragging stones through and from Avebury, the former greatest stone circle, might have played a part in events.

The recent discovery of Stukeley’s drawing of 1723 raised the possibility of an undiscovered route by which the sarsens were brought from Avebury and Clatford to Stonehenge.

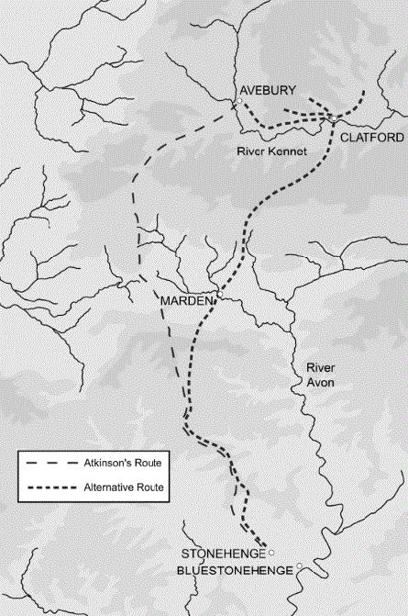

Atkinson’s preferred history for the sarsen stones was:

- They were quarried at unknown locations on the Marlborough Downs.

- They were then dragged to Avebury to be erected.

- At a later date, some of these were dismantled and, together with newly quarried stones, were dragged southwest from Avebury toward Devizes.

- Then they were dragged southward past Bishops Cannings to avoid the steep downward slope of the Vale of Pewsey.

- In the bottom of the Vale’s western end, south of Etchilhampton, the stone pullers could have avoided the streams to the east and headed for the steep slope rising upward to the northern edge of Salisbury Plain at Redhorn Hill; this would have been the most difficult part of the route, perhaps requiring a dog-leg ascent.

- Once on the Plain, it would have been easy pulling along a ridgeway with a minimum of rise and fall.

In 1961 a geologist named Patrick Hill suggested an alternative route.

6

He thought Atkinson’s route was four miles longer than it needed to be and that the ascent of Redhorn Hill was unnecessary and too steep:

- Hill’s preferred starting point was at Lockeridge, three miles east of Avebury in the direction of Marlborough.

- From here, his route climbs gradually to the saddle next to the causewayed enclosure of Knap Hill, then drops down the escarpment on the north side of the Vale of Pewsey, where it skirts east of Woodborough Hill.

- It then heads south to the Avon valley, eventually following the route of the Stonehenge Avenue from West Amesbury into Stonehenge. Within the Avon valley, Hill reckoned the stones were dragged on land rather than floated on the river because of the shallow depth of water. He did think it possible, however, that they might have been dragged through the water over short distances to avoid riverside bluffs, and when crossing the river at various points.

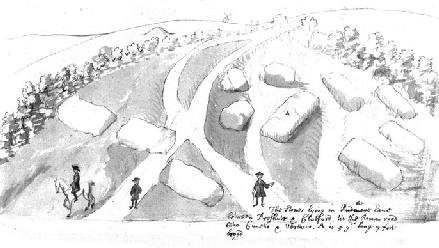

Since then, very little has been published on quarries and routes for the Stonehenge sarsens, though I’m sure that many enthusiasts have given it a lot of thought. I’d never really dwelt on the question until I received an email from Josh in 2008. He was finishing his project on Avebury, and his researcher Rick Peterson had turned up a forgotten manuscript in Oxford’s Bodleian Library. It is a sketch by William Stukeley of some sarsen stones that he’d noticed on the roadside in 1723 between Avebury and Marlborough, near the villages of Clatford and Preshute, north of

Lockeridge. Three frock-coated gentlemen, one of them on a horse, are depicted next to a group of eleven recumbent sarsens, the largest of which is annotated as being “5 yds long 7 foot broad.” Not only do these dimensions match those of the sarsen circle uprights, but Stukeley also depicts this largest stone and seven others as distinctly rectangular, as if they’d been shaped.

7

John Aubrey saw these particular stones at Clatford and described them as “rudely hewen.”

The last time I’d seen a picture that was this much fun—X marks the spot—was when someone sent me a pirate’s map showing Captain Kidd’s stronghold on an island off the coast of Madagascar. Stukeley’s drawing is potentially a treasure map in terms of locating the source of the sarsens. Josh and I mulled over the possibilities. This place could have been a marshaling point where partly shaped sarsens were brought prior to being sent on the final leg of the journey to Stonehenge. The stones Stukeley saw could also have been the products of a single quarry, one among many, all working to make the Stonehenge sarsens. Finally, we could not rule out these stones having being quarried many centuries later—leftovers from Medieval or later stonemasons—although the Medieval masons’ technique was to break stones into smaller, more manageable blocks before hauling them away. Indeed, someone did later take away the stones Stukeley saw: Nothing remains at this spot today.

I visited the place first with Peter Dunn (the reconstruction artist who has provided many of the images for this book), and later identified the exact spot with Kate Welham’s survey team in 2011. Our geophysical survey failed to reveal holes for standing stones, so the shaped sarsens were probably never erected here but had lain prone. Close by, we detected the ditch and external bank of an unrecorded small henge. Perhaps the stones were brought to this marshaling point from the higher ground to the north, in which direction sarsens still lie in the upper parts of the dry valleys that descend from the Marlborough Downs. In the valley below Stukeley’s stones at Clatford (the ford of the marsh marigold), a ford crosses the River Kennet. In August 2011, our team hand-drilled cores into the river mud here to reveal what could be the remains of a buried causeway of sarsen boulders and river flints; future excavation should reveal whether this crossing was used to transport stones to Stonehenge.

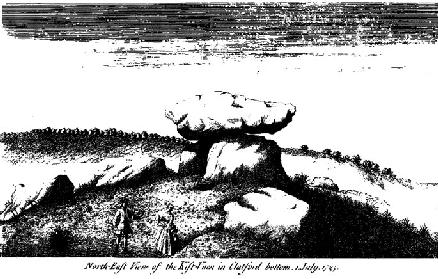

William Stukeley drew the abandoned but shaped sarsens at Clatford in 1723. The stones have gone and the road has moved, but we have identified the precise spot from the positions of the round barrow and the windmill.