Stories for Boys: A Memoir (3 page)

Read Stories for Boys: A Memoir Online

Authors: Gregory Martin

My mother stared back. Her eyes did not leave his. She said, “You need to be gone by tomorrow.”

My father slept that night in the guest bedroom. He spent Tuesday and Wednesday with Chris in a hotel. My mother left for work early in the morning, and my father came back to the house from the hotel, and my brother and I helped him pack boxes and rent the U-Haul. My father had moved many times before, but he seemed to have forgotten how the process worked. My brother and I passed him carrying boxes, while he stood in the kitchen, the bedroom, the basement, the driveway, staring into the middle distance. Figuring out how everything fit in the truck was not nearly as enjoyable as usual.

On Thursday, Chris and I helped our father move into a cheap apartment across town. It was the first apartment we looked at. As we pulled into the parking lot that morning, I thought of the apartment my father grew up in, near the railroad tracks in Newport News. We walked through the empty rooms with beige carpet and bare white walls. My father turned to the manager, an older lady with a smoker’s cough, white hair, and a Mickey Mouse t-shirt, and he said, “Okay. I’ll take it.” We walked outside and down the steps. In the courtyard, a little boy about Evan’s age was having lunch by himself at a picnic table chained to a tree.

Resilience

THE SUNDAY AFTER MY FATHER WAS DISCHARGED FROM the hospital happened to be Mother’s Day. I was still in Spokane. My brother had flown back to Maryland the day before. I missed Christine and the boys, but whatever had been vital and urgent in my daily life in Albuquerque felt suspended, as if my father had died, as if he’d committed rather than attempted suicide.

I felt shattered. Late at night on the phone, I talked and talked to Christine, and she listened. Christine is a talented listener. Unlike me, she doesn’t interrupt with highly workable solutions, with suggestions and advice, with interpretations of significance. She just let me talk. I didn’t have to make sense of anything.

Christine said, “I’m so sorry.” And, “I wish I could be there with you.” And, “You must be so sad.”

For seven years, my life had been dominated by fatherhood. I was not used to thinking of myself as a son. I was not used to thinking of myself as deceived. I was not used to thinking much about my father at all. When I thought of my parents – no, when I worried about my parents – I worried about my mother’s ovarian cancer and her chemotherapy, or I worried about whether or not my father was making sure that my mother was taking her bipolar medication. I needed my father to keep his eye on things. It never once occurred to me that my mother might need to keep a closer eye on him.

I stayed in Spokane for nearly two weeks. I didn’t feel ready to leave my mother on her own. Another way to say this is that I needed her to not be alone because I couldn’t bear the sadness she had to bear.

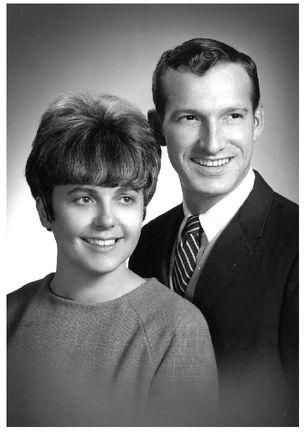

MY MOTHER AND father loved each other. Their love was unferocious, grudgeless, without jealousy or tyranny, delirium or disdain. It was playful, gentle. A love hard to find in books. It was rooted in an abiding friendship and a mutual, lifelong desire for each other’s company. They often abandoned me to friends and neighbors and went, of all places, to garage sales and auctions. Their zeal for garage sales and auctions was matched by many things, like bowling, like playing cribbage or two-handed pinochle late into the evening. They went for walks; they read books side by side for hours upon hours.

When I was a child, we’d gather in the living room, and my father would play folk songs on the guitar, and we’d all sing. “Michael Row Your Boat Ashore” and “Blowing in the Wind” and “Five Hundred Miles” and “Hard Times Come Again No More.” My father’s voice was, and still is, deep and soulful. My mother cannot carry a tune. She has – and she will freely admit this – a terrible singing voice. All through my childhood, my mother’s voice threatened to pull each of us away from the melody. The quality of her singing voice was often acknowledged. My mother sang anyway, gleefully, and I’m guessing now that my father loved her even more for this. Of course he did. Sometimes at the end of a song, my mother said, “God hears my true voice.” And my father would say, “Of course he does.” Or, “He must.” Or, “I hear it, too.”

These days, the implicit code is that parents put their love of their children first, before their love for one another, and only controversial parents are willing to declare that they put their love for their spouses first. When I was growing up, I unconsciously understood that my parents’ love for each other was always first, and then came their love for their children. I did not question this. I had no reason to question it. Nothing seemed wrong.

NINE DAYS AFTER my father attempted suicide, my mother and I went bowling. She did not want to stay at home, perfecting her dignity and resilience. She was sixty-seven. Her hair was more gray and white than black and more thin since it had grown back after the chemotherapy four years earlier. She had a red scar down the middle of her nose from the surgery to remove skin cancer a few years before that. Both cancers were in remission. She worked full time as a university dean. She walked three miles a day. She ate steel-cut oatmeal with fresh fruit for breakfast. She ate a sweet potato with cinnamon for lunch. She drank her English breakfast tea with a splash of sweetened, condensed milk. She’d grown up in a small town in northern Nevada, and as a young woman was accomplished with a rifle and one winter even ran a trap-line and sold beaver and mink and fox pelts, but now she did yoga once a week. She bowled on teams in two different leagues. Summer league would be starting in a few weeks, and she needed to practice.

When I was a boy growing up in Nebraska, my mother and I bowled together in the Cornstalk and Kernel league. We cleaned up; we took first place several years running. This may be mythmaking, but in my memory, one year we each had high average and high score in our respective parent/child categories.

In May of each year, my mother and her sister, my aunt Di, travel to a different mid-sized city – Topeka, Oklahoma City, Reno – bowling in the Senior U.S. Nationals. Every October, they bowl in the World Senior Games in St. George, in southern Utah. My mother doesn’t rattle. She has uncanny consistency. Her address and approach are always the same – three steps, a slight hop, her backswing in a single plane, her knee bent low at release, her follow-through as if she were about to shake your hand. She throws the same first ball every time. One year, at Nationals, she and her doubles partner took second place out of 7,322 other doubles teams.

But on this particular day, my mother was off her mark. She threw bedpost splits and baby splits. She kept hitting the Brooklyn side of the headpin. Her ball drifted toward the gutter as if drawn by a magnet. If she knocked down eight pins, one of the remaining pins was hidden, a sleeper. She threw open frame after open frame. No strikes, no spares. All this, despite having her own monogrammed ball, her own shoes, her own wrist brace and powder and towel. I was wearing worn-out red and green rental shoes. The thumbhole of my rental ball was too loose. But I struck the pocket flush. I threw strike after strike. It was my day. I had great action, the pins flying and mixing. The first two games weren’t even competitive. My mother bowled more than thirty pins below her average. I didn’t have an average – I hadn’t bowled in a few years – but if I bowled like this all the time, I could quit my job as a teacher and join the tour. I could be on ESPN2.

My mother said, “Does Christine have any idea about the secret life you’ve been leading at Holiday Bowl?”

I shook my head but didn’t laugh. I didn’t turn to look at her. I was looking down the shiny lane at the pins, set up in their orderly configuration. I had always appreciated my mother’s black humor, but I wasn’t ready to hear it just then. I didn’t want to think about my father. I didn’t want to think at all. This is something I can do, something I’ve always been able to do. Put things away – events, feelings – put them far from my mind and my heart.

I wanted to throw a strike, and I did. I walked back to take my seat. “Christine has no idea,” I said.

The third game was closer. I’d been trying to throw strikes, but with my second ball, I sandbagged a few of the spares. I wanted to at least make it close, but at the same time, I didn’t want my mother to know. She wouldn’t like that. My mother was the only person I knew who hated losing more than I did – at anything, it didn’t matter what, pinochle, horseshoes, you name it – but she wanted to win fair and square. She was fierce about fairness. On my last ball, for a spare in the tenth frame, I guttered a makeable leave. I lost by three pins.

My mother said, “You did that on purpose.”

I thought I would lie, but found that I couldn’t. “I did. Yes.”

“I wouldn’t have done that,” my mother said fiercely. Seriousness was all over her face. “I would have beat you.”

“I know.”

Don’t Go There

THE NEXT DAY, I DROVE OVER TO MY FATHER’S CHEAP apartment. My father had been there for five days. Unopened boxes were everywhere. I told him it was time to unpack. He shrugged. He stood there with his hands at his sides, watching me look around, taking in this new life. There was nowhere for him to sit down. No La-Z -Boy recliner with its worn, wooden handle. No sofa. Two folding chairs leaned against the wall.

I found his small pocketknife on the counter next to his keys and started cutting open boxes. One of the first things I unwrapped from the crumpled newspaper was a glass ashtray. I held it in my hand; it was heavy. I was baffled.

My father saw me sitting there, cross-legged on the beige carpet, holding the ashtray. He said, “I smoke.”

I’d thought my father had given up smoking when I was six or seven, after he got tired of me taking his cartons from the refrigerator and burying them at the bottom of the neighbor’s trash. I stared at him. Gray and white hair sprouted from the v – neck of his white t-shirt. He wore jeans and was in his bare feet. There was nothing unusual about this. My father was not a man who wore golf shirts and khakis on the weekends. But he looked disheveled to me now. I had the sense that if I had not been there he’d lay back down on the unmade bed and stare at the ceiling. He was still standing by the door.

“I tried to quit I don’t know how many times. But I never really did.”

My father has severe asthma and chronic bronchitis. I decided to name my feelings, something Christine and I were trying to teach the boys to do at home. But instead of saying “I’m angry,” I said “I feel like throwing this at your head.”

My father thought about this. He went over and started unfolding the card table which would now be his dining room table. Then he said, “You’ve always had good aim.” He didn’t look up. He took paperbacks from another box and stacked them in a pile against the wall. He didn’t have a bookshelf.

All morning I vacillated between feeling nauseated with sadness and disbelief and losing myself in the task at hand and making small comments like, “Where do you want this?” and opening the window and saying, “It’s a really nice day.” Because it was. It was another warm, early summer day in Spokane. My father and I settled into the work of unpacking, arranging his apartment. We set up his modular office furniture in the spare bedroom. We talked about what he’d need to do to set up his internet connection.

I hate this feeling – the lapsing into normalcy when things are anything but normal. I wonder if other people despise it as much as I do. Everything about the big picture is wrong, and I’m making turkey sandwiches on white bread with mayo and mustard and iceberg lettuce for my father and me for lunch, and my mouth is watering, and we sit down at the card table, on folding chairs, and eat, and for a few moments, this feels as familiar and normal and seemingly uneventful as any other turkey sandwich I’ve eaten with my father over the years. My father is an easy man to eat lunch with; he’s agreeable, warm, quick to laugh, skilled at finding common ground, good at asking the kinds of questions that draw people out and get them to talk about things that matter to them. My father was asking me about the boys’ summer plans, and I was talking about swim team and art camp, and it was almost as if I’d forgotten how awful things were. I was no longer trying to separate what was done to my father when he was a boy, when he was an innocent, from what my father did to my mother, for nearly forty years, when he was culpable, accountable. I’d stopped trying to untangle my confused sympathies, and so when my father said, “It’s too bad we don’t have potato chips,” I added, without thinking, “Christine would cut up an apple. We don’t get to have potato chips at lunch.”

Other books

This Is All by Aidan Chambers

Hidden Scars by Amanda King

Only Mine by Susan Mallery

My Friend Leonard by James Frey

Champion by Jon Kiln

The Pirates Own Book by Charles Ellms

The Cost To Play (Slivers of Love) by Gaines, Oliva

The Judgment by William J. Coughlin

Button Down by Anne Ylvisaker

Matt Christopher's Baseball Jokes and Riddles by Matt Christopher, Daniel Vasconcellos