Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (40 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

Retracing our steps and passing Nak

ş

idil’s türbe, we walk along Aslanhane Soka

ğ

ı

, the Street of the Lion-House, and soon find ourselves back once again on the main avenue, Fevzi Pa

ş

a Caddesi. We continue on across the avenue, taking the street which runs down the hill past the west side of the medrese of Feyzullah Efendi; from here we will stroll through the neighbourhood to the south and west of Fatih Camii.

Proceeding downhill, we take the second turning on our right and then one block along on our left we come upon an ancient mosque, Iskender Pa

ş

a Camii. It is dated 1505, but it is not certain who the founder was; he is thought to have been one of the vezirs of Beyazit II who was governor of Bosnia. It is a simple dignified building with a blind dome on pendentives resting on the walls; the three small domes of the porch are supported on ancient columns with rather worn Byzantine capitals. The

ş

erefe of the minaret has an elaborately stalactited corbel, but the curious decoration on top of the minaret probably belongs to an eighteenth-century restoration. The mosque has many characteristics in common with Bali Pa

ş

a Camii, which we will see a little farther on along our itinerary; both are of about the same date.

MONASTERY OF CONSTANTINE LIPS

Continuing on in the same direction we come at the next turning to Hal

ı

c

ı

lar Caddesi, where we turn left and stroll downhill for a few blocks. At the corner where it runs into the wide new Vatan Caddesi is a large Byzantine church, called Fenari Isa Camii, or the Monastery of Constantine Lips. The church has been investigated and partially restored by the Byzantine Institute and what follows is a summary of the conclusions reached.

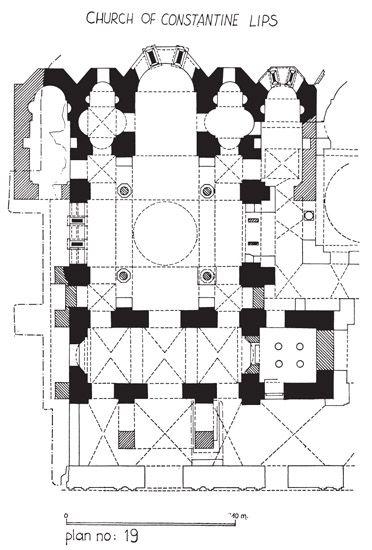

This complicated building, constructed at different dates, consists of two churches, with a double narthex and a side chapel; its original structure had been profoundly altered in Ottoman times when it was converted into a mosque. The first church on the site, the one to the north, was dedicated in 907 to the Theotokos Panachrantos, the Immaculate Mother of God, by Constantine Lips, a high functionary at the courts of Leo the Wise and Constantine Porphyrogenitus. It was a church of the four-column type (the columns were replaced by arches in the Ottoman period); but quite unusually it had five apses, the extra ones to north and south projecting beyond the rest of the building. The northern one is now demolished, the southern one incorporated into the south church. Another unusual, perhaps unique, feature is that there are four little chapels on the roof, grouped round the main dome. Some 350 years after this northern church was built, the Empress Theodora, wife of Michael VIII Palaeologus (r. 1261–82), refounded the monastery and added another church to the south, an outer narthex for both churches, and a chapel to the south of her new church; the additions were designed to serve as a mortuary for the Palaeologan family. The new church, dedicated to St. John the Baptist, was of the ambulatory type, that is its nave was divided from the aisles by a triple arcade to north, west and south, each arcade supported by two columns. (All this was removed in Ottoman times, but the bases of some of the columns still remain and one can see the narrow arches of the arcades above, embedded in the Turkish masonry.) Of its three apses, the northern one was the southern supernumerary apse of the older church. Thus there were in all seven apses, six of which remain and make the eastern façade on the building exceedingly attractive. On the interior a certain amount of good sculptured decoration survives in cornices and window frames, especially in the north church.

MEDRESE OF SELIM I

Vatan Caddesi runs along the ancient course of the Lycus River through a district called Yeni Bahçe, the New Garden. Until recently this was mostly garden land and a certain number of vegetable gardens still survive, but there is nothing much of interest along the new road except the medrese and türbe immediately to be described. Not far west of Constantine Lips, on the other side of Vatan Caddesi, a large and handsome medrese has recently been restored. This is the medrese of Selim I, the Grim, built in his memory by his son, Süleyman the Magnificent; the architect was Sinan. The 20 cells of the students occupy three sides of the courtyard, while on the fourth stands the large and handsome lecture-hall, which was at one point turned into a mosque. The original entrance, through a small domed porch, is behind the dershane and at an odd angle to it, and the wall that encloses this whole side is irregular in a way that is hard to account for. Nevertheless, the building is very attractive and once inside one does not notice its curious dissymmetry.

Just west of this medrese across a side street stands a türbe and a mektep in a walled garden. One enters the gaily planted garden by a gate in the north wall and on the left is an octagonal türbe, that of

Ş

ah Huban Kad

ı

n, a daughter of Selim I who died in 1572. This too is a work of the great Sinan. While there is nothing remarkable about the türbe, the mektep is a grand one. It is double; that is, it consists of two spacious square rooms each covered by a dome and containing an elegant ocak, or fireplace. The wooden roof and column of the porch are modern, part of the recent restoration, but they perhaps replace an equally simple original. The building now serves as an outpatient clinic for mental illnesses.

Recrossing Vatan Caddesi, we take the avenue just opposite, Akdeniz Caddesi, and walk uphill once again. We then take the fourth turning on the left into Hüsrev Pa

ş

a Soka

ğ

ı

and at the next corner on the left we come to a very handsome and elaborate türbe. It is by Sinan and was built for Hüsrev Pa

ş

a, a grandson of Beyazit II. Hüsrev Pa

ş

a had been one of the leading generals at the battle of Mohacz in 1526, when the fate of Hungary was decided in less than two hours. He governed Bosnia for many years with great pomp and luxury but also with severe justice. While governor of Syria he founded a mosque at Aleppo in 1536–7 which is the earliest dated building of Sinan and is still in existence. While Beylerbey of Rumelia and Fourth Vezir in 1544, he fell into disgrace because of his complicity in a plot against the Grand Vezir Süleyman Pa

ş

a. Despairing because of his fall from power, he took his own life soon afterwards by literally starving himself to death, one of the very rare incidents of suicide among the Ottomans. The türbe of Hüsrev Pa

ş

a is octagonal in form, the eight faces being separated from each other by slender columns which run up to the first cornice, elaborately carved with stalactites; the dome is set back a short distance and has another cornice of its own, also carved.

We now make a short detour on the street which runs uphill directly opposite the türbe. Just past the first intersection and on the right side of the street we see a fine mosque with a ruined porch. An inscription over the portal states that it was built in 1504 by Huma Hatun, daughter of Beyazit II, in memory of her late husband, Bali Pa

ş

a, who had died in 1495. Since this mosque appears in the

Tezkere

, the listing of Sinan’s works, we conclude that Sinan rebuilt Bali Pa

ş

a Camii some time later on, though whether on its old plan or a new one it is impossible to say. The plan of Bali Pa

ş

a Camii is simple and to a certain extent resembles that of Iskender Pa

ş

a, which we saw earlier on our tour. The chief difference between these two is that in Bali Pa

ş

a the dome arches to north, west and south are very deep, being almost barrel vaults; thus room is left, on the north and south, for shallow bays with galleries above. The mosque was severely injured in the earth quake of 1894 and again in the fire of 1917; it was partially restored in 1935 and further work has been done on it in recent years. But the five domes of the porch have never been rebuilt and this gives the façade a somewhat naked look.

S

İ

NAN’S MESC

İ

T

After leaving Bali Pa

ş

a Camii we return to Hüsrev Pa

ş

a Soka

ğ

ı

and continue on in the same direction. We then take the second turning on the left, on Ak

ş

emseddin Caddesi, and walk one block downhill. There, at the corner to our left, we come upon Mimar Sinan Mescidi, part of a vak

ı

f founded by the great architect himself in 1573–4. The present mosque is brand new, except for the minaret, replacing the original mescit, which had long ago disappeared. The original mosque was rather irregular, consisting of two rectangular rooms with a wooden roof. The minaret is of a very rare type, perhaps the only one of its kind that Sinan ever built. It is octagonal and without a balcony; instead, at the top, a decorated window in each of the eight faces allows the müezzin to call to prayer. Although a very minor antiquity indeed, this lonely minaret stands as a monument to the great Sinan – may it be preserved forever from the modern tenements which encroach upon it.