Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (43 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

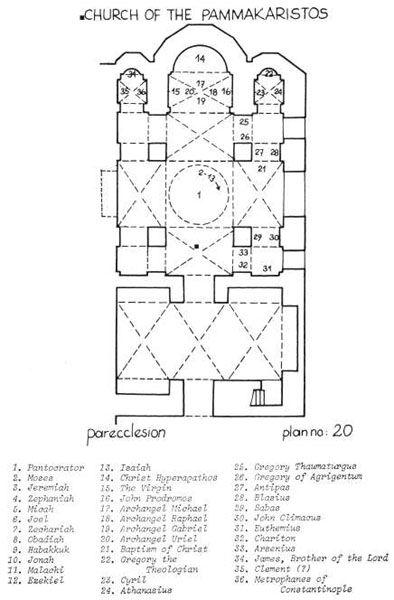

The building consists of a central church with a narthex; a small chapel on the south; and a curious “perambulatory” forming a side aisle on the north, an outer narthex on the west, and two bays of an aisle on the south in front of the side chapel. Each of these three sections was radically altered when it was converted into a mosque in 1591. The work of the Byzantine Institute has at last cleared up many of the puzzles arising from the various periods of construction and transformation. It now appears that the main church was built in the twelfth century by an otherwise unknown John Comnenus and his wife Anna Doukaina. In form, the church was on the ambulatory type, a triple arcade on the north, west and south dividing the central domed area from the ambulatory; at the east end were the usual three apses, at the west a single narthex. At the beginning of the fourteenth century a side chapel was added at the south-east as a mortuary for Michael Glabas and his family; this was a tiny example of the four-column type. In the second half of the fourteenth century, the north, west and part of the south sides were surrounded by the “perambulatory”, which ran into and partly obliterated the west façade of the side chapel. When the building was converted into a mosque, the chief concern seems to have been to increase the available interior space.

Most of the interior walls were demolished, including the arches of the ambulatory; the three apses were replaced by the present domed triangular projection; and the side chapel was thrown into the mosque by removing the wall and suppressing the two northern columns. All this can scarcely be regarded as an improvement. Indeed, the main area of the church has become a dark, planless cavern of shapeless hulks of masonry joined by low crooked arches. This section has now been divided off from the side chapel and is again being used as a mosque.

The side chapel has been most beautifully restored, its missing columns replaced, and its mosaics uncovered and cleaned. The mosaics of the dome have always been known, for they were never concealed, but they now gleam with their former brilliance: the Pantocrator surrounded by 12 Prophets; in the apse Christ “Hyperagathos” with the Virgin and St. John the Baptist; other surfaces contain angels and full-length figures of saints. Only one scene mosaic survives: the Baptism of Christ. Though much less in extent and variety than the mosaics of Kariye Camii (see Chapter 14), these are nevertheless an enormously precious addition to our knowledge of the art of the last renaissance of Byzantine culture in the early fourteenth century.

The Church of the Pammakaristos remained in the hands of the Greeks for some time after the Conquest; in fact, in 1456 it was made the seat of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate after the Patriarch Gennadius abandoned the Church of the Holy Apostles. It was in the side-chapel of the Pammakaristos that Mehmet the Conqueror came to discuss questions in religion and politics with Gennadius. The Pammakaristos continued as the site of the Patriarchate until 1568; five years later Murat III converted it into a mosque. He then called it Fethiye Camii, the Mosque of Victory, to commemorate his conquest of Georgia and Azerbaijan.

CHURCH OF ST. JOHN IN TRULLO

Returning to Fethiye Caddesi we follow it in the same direction for a short distance and then take the first turning on the right. We there find ourselves face to face with a charming little Byzantine church which has recently been restored. It is called Ahmet Pa

ş

a Mescidi and has been identified with almost virtual certainty as the Church of St. John the Baptist in Trullo. Nothing whatever is known of the history of the church in Byzantine times. Three years after the Conquest, in 1456, when Gennadius transferred the Patriarchate to the Pammakaristos, he turned out the nuns there ensconced and gave them this church instead. Here they seem to have remained until about 1586, when the church was converted into a mosque by Hirami Ahmet Pa

ş

a, from whom it takes its Turkish name. The tiny building was a characteristic example of the four-column type of church with a narthex and three semicircular apses, evidently of the eleventh or twelfth century. Until a few years ago it was ruined and dilapidated, but still showed signs of frescoes under its faded and blotched whitewash. The original four columns, long since purloined, have since been replaced with poor columns and awkward capitals, and the restored brickwork is also wrong.

MEHMET A

Ğ

A CAM

İ

İ

Returning to the main avenue, we take the next right and at the end of the short street we see a small mosque in its walled garden. Though of modest dimensions, this is a pretty mosque and interesting because it is one of the relatively few that can be confidently attributed to the architect Davut A

ğ

a, Sinan’s colleague and successor as Chief Architect to the Sultan. Over one of the gates to the courtyard is an inscription naming Davut as architect and giving the date A.H. 993 (A.D. 1585), at which time Sinan was still alive. The founder Mehmet A

ğ

a was Chief of the Black Eunuchs in the reign of Murat III.

In plan the mosque is of the simplest: a square room covered by a dome, with a projecting apse for the mihrab and an entrance porch with five bays. But unlike most mosques of this simple type, the dome does not rest directly on the walls but on arches supported by pillars and columns engaged in the wall; instead of pendentives there are four semidomes in the diagonals. Thus the effect is of an inscribed octagon, as in several of Sinan’s mosques, but in this case without the side aisles; it rather resembles Sinan’s mosque of Molla Çelebi at F

ı

nd

ı

kl

ı

on the Bosphorus (see Chapter 21). The effect is unusual but not unattractive. The interior is adorned with faience inscriptions and other tile panels of the best Iznik period; but the painted decoration is tasteless – fortunately it is growing dim with damp. Mehmet A

ğ

a’s türbe is in the garden to the left; it is a rather large square building.

Just to the south outside the precincts stands a handsome double bath, also a benefaction of Mehmet A

ğ

a and presumably built by Davut A

ğ

a. The general plan is standard: a large square camekân, the dome of which is supported on squinches in the form of conches; a cruciform hararet with cubicles in the corners of the cross, but the lower arm of the cross has been cut off and turned into a small so

ğ

ukluk which leads through the right-hand cubicle into the hararet; in the cubicles are very small private washrooms separated from each other by low marble partitions – a quite unique disposition. As far as one can judge from the outside, the women’s section seems to be a duplicate of the men’s.

LIBRARY OF MURAT MOLLA

Returning once again to the avenue, which here changes its name to Manyasizade Caddesi, we continue along in the same direction and take the next left. A short way along to the right we see the fine library of Murat Molla. Damatzade Murat Molla was a judge and scholar of the eighteenth century who founded a tekke, now destroyed, to which he later (1775) added a library that still stands in an extensive and very pretty walled garden. The library is a large square building of brick and stone supported by four columns with re-used Byzantine capitals – the whole edifice indeed is built on Byzantine substructures, fragments of which may be seen in the garden. The corners of the room also have domes with barrel vaults between them. In short, it is a very typical and very attractive example of an eighteenth-century Ottoman library, to be compared with those of Atif Efendi, Rag

ı

p Pa

ş

a and others of the same period. Like these, it is constantly in use.

ISMA

İ

L EFEND

İ

CAM

İ

İ

We now return to Manyasizade Caddesi and at the next corner on the left we come to Ismail Efendi Camii. This is a quaint and entertaining example of a building in a transitional style between the classical and the baroque. It was built by the

Ş

eyh-ül Islam Ismail Efendi in 1724. The vaulted substructure contains shops with the mosque above them, so constructed, according to the

Hadika,

in order to resemble the Kaaba at Mecca! We enter the courtyard through a gate above which is a very characteristic sibyan mektebi of one room. To the right a long double staircase leads up to the mosque, the porch of which has been tastelessly reconstructed in detail (e.g., the capitals of the columns!), but the general effect of which is pleasing except for its glazing. On the interior there is a very pretty – perhaps unique – triple arcade in two storeys of superposed columns repeated on the south, west and north sides and supporting galleries; perhaps because of these arcades the dome seems unusually high. At the back of the courtyard is a small medrese, or more specifically a dar-ül hadis, school of tradition. It has been greatly altered and walled in, but it is again being used for something like its original purpose, a school for reading the Kuran. All-in-all this little complex is quite charming with its warm polychrome of brick and stone masonry; it was on the whole pretty-well restored from near ruin in 1952.

CISTERN OF ASPAR

Returning once again to Manyasizade Caddesi, we continue along for a few paces and then take the next left into Sultan Selim Caddesi. As we walk along we now see on our right a great open cistern, the second of the three ancient Roman reservoirs in the city. This is the Cistern of Aspar, a Gothic general put to death in the year 471 by the Emperor Leo I. This is the largest of the Roman reservoirs; it is square, 152 metres on a side, and was originally ten metres deep. Some years ago one could still see its original construction in courses of stone and brick, with shallow arches on its interior surface. Up until 1985 the cistern was occupied by a very picturesque little farm village whose house-tops barely reach to the level of the surrounding streets, but then the houses were demolished to convert the cistern into a market area. Nevertheless, it is a superb setting for the great mosque of Sultan Selim I that looms ahead at the far end of the cistern.

MOSQUE OF SULTAN SEL

İ

M I

The mosque of Sultan Selim I rises on a high terrace overlooking the Golden Horn with an extensive and magnificent view. And the building itself, with its great shallow dome and its cluster of little domes on either side, is impressive and worthy of the site. The courtyard is one of the most charming and vivid in the city, with its columns of various marbles and granites, the polychrome voussoirs of the arches, the very beautiful tiles of the earliest Iznik period in the lunettes above the windows – turquoise, deep blue, and yellow – and the fountain surrounded by tapering cypress trees. The plan is quite simple: a square room, 24.5 metres on a side, covered by a shallow dome, 32.5 metres in height under the crown, which rests directly on the outer walls by means of smooth pendentives. The dome, like that of Haghia Sophia, but unlike that of most Turkish mosques, is significantly less than a hemisphere. This gives a very spacious and grand effect, recalling a little the beautiful shallow dome of the Roman Pantheon. The room itself is vast and empty, but saved from dullness by its perfect proportions and by the exquisite colour of the Iznik tiles in the lunettes. The mosque furniture though sparse is fine, particularly the mihrab, mimber, and sultan’s loge. The border of the ceiling under the loge is a quite exceptionally beautiful and rich example of the painted and gilded woodwork of the great age; notice the deep, rich colours and the varieties of floral and leaf motifs in the four or five separate borders, like an Oriental rug, only here picked out in gold. To north and south of the great central room of the mosque there are annexes consisting of a domed cruciform passage giving access to four small domed rooms in the corner. These served, as we have seen elsewhere in the earlier mosques, as tabhanes, or hospices, for travelling dervishes.

The mosque was finished in 1522 under Süleyman the Magnificent, but it may have been begun two or three years earlier by Selim himself, as the Arabic inscription over the entrance portal would seem to imply. Although the mosque is very often ascribed to Sinan, even by otherwise reliable authorities, it is certainly not so, for not only is it too early but it is not listed in the

Tezkere.

Unfortunately the identity of the actual architect has not been established.

In the garden behind the mosque is the grand türbe of Selim I, octagonal and with a dome deeply ribbed on the outside. In the porch on either side of the door are two beautiful panels of tilework, presumably from Iznik but unique in colour and design. The interior has unfortunately lost its original decoration, but it is still impressive in its solitude, with the huge catafalque of the Sultan standing alone in the centre of the tomb, covered with embroidered velvet and with the Sultan’s enormous turban at its head. As Evliya Çelebi wrote of this türbe: “There is no royal sepulcher which fills the visitor with so much awe as Selim’s. There he lies with the turban called Selimiye on his coffin like a seven-headed dragon. I, the humble Evliya, was for three years the reader of hymns at his türbe.”