Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (5 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

This second golden age lasted longer than did the first, for the Ottoman Empire was still vigorous and expanding as late as the middle of the seventeenth century, 100 years after the death of Süleyman. But by that time signs of decadence were already apparent in the Empire. During the century after Süleyman the Ottoman armies and navies suffered several defeats, and territory was lost in Transylvania, Hungary and Persia. There were also symptoms of decay within the Empire, whose subjects, both Muslims and Christians, were suffering from the maladministration and corruption which had spread to all levels of the government. One of the principal causes of this decay was to be found in the Sultanate itself, for the successors of Süleyman ceased to lead their armies in the field, preferring to spend their time with their women in the Harem. By the end of the sixteenth century the Empire was literally ruled by these women, the mothers of the sultans or their favourite concubines, who ran the country to satisfy their own personal ends, to its great detriment. The situation seemed to improve for a time during the reign of Sultan Murat IV, who ruled from 1623 till 1640. The young Sultan, who was only 14 when he ascended the throne, proved to be a strong and able ruler and checked for a time the decline of the Ottoman Empire. He was the first sultan since Süleyman to lead his army in battle and was victorious in several campaigns, climaxed by the recapture of Baghdad in 1638. But Murat’s untimely death at the age of 30 ended this brief revival of the old martial Ottoman spirit, and after his reign the decay proceeded even more rapidly than before.

Nevertheless, the Ottoman Empire was still vast and prosperous and some of its institutions remained basically sound, so that it held together for centuries after it had passed its prime. And although the Ottoman armies suffered one defeat after another in the Balkans, Istanbul was little affected, for the frontiers were far away and wealth continued to pour into the capital. Members of the royal family and the great and wealthy men and women of the Empire continued to adorn the city with splendid mosques and pious foundations, while the Sultan continued to take his pleasure in the Harem.

But by the end of the eighteenth century the fortunes of the Empire had declined to the point where its basic problems could no longer be ignored, not even in the palace. The Empire gave up large portions of its Balkan territories in humiliating peace treaties after losing wars with European powers. Within, the Empire was weakened by anarchy and rebellion and its people were suffering even more grievously than before. This led to social and political unrest, particularly among the subject Christians, who now began to nourish dreams of independence.

During this period the Ottoman Empire was being increasingly influenced by developments in western Europe, particularly by the liberal ideas which brought about the French Revolution. This eventually led to a movement of reform in the Ottoman Empire. The first sultan to be deeply influenced by these western ideas was Selim III, who ruled from 1789 till 1807. Selim attempted to improve and modernize the Ottoman army by reorganizing and training it according to western models. By this he hoped to protect the Empire from encroachments by foreign powers and from rebellion and anarchy within its own borders. But Selim’s efforts were resisted and eventually frustrated by the Janissaries, the elite corps of the old Ottoman army, who felt that their privileges were being threatened by the new reforms. The Janissaries were finally crushed in 1826 by Sultan Mahmut II, who thereupon instituted an extensive programme of reforms in all of the basic institutions of the Empire, reshaping them along modern western lines. This programme continued for a time during the reigns of Mahmut’s immediate successors, Abdül Mecit I and Abdül Aziz. The reform movement, or Tanzimat, as it was called, culminated in 1876 with the promulgation of the first Ottoman constitution and the establishment of a parliament, which met for the first time on 19 March of the following year. But this parliament was very short-lived, for it was dissolved on 13 February 1878 by Sultan Abdül Hamit II, then in the second year of his long and oppressive reign. Nevertheless, the forces of reform had now grown too strong to be held down permanently. The pressures they generated eventually led, in 1909, to the deposition of Abdül Hamit and to the restoration of the constitution and the parliament in that same year. But the next decade, which seemed so full of promise at its beginning, was a sad and bitter one for Turkey. The country found itself on the losing side in the First World War, after which the victorious Allies proceeded to divide up the remnants of the Ottoman Empire amongst themselves. Turkey was saved only by the heroic efforts of its people, who fought to preserve their homeland when it was invaded by the Greeks in 1919.

Their leader in this War of Independence, which was finally won by Turkey in 1922, was Mustafa Kemal Pa

ş

a, later to be known as Atatürk, the Father of the Turks. Even before the conclusion of the war, Atatürk and his associates had laid the foundations of the new republic which would arise out of the ruins of the Ottoman Empire. The Sultanate was abolished in 1922 and on 29 October of the following year the Republic of Turkey was formally established, with Kemal Atatürk as its first President. During the remaining 15 years of his life Atatürk guided his countrymen to a more modern and western way of life, a process which still continues in Turkey today. Kemal Atatürk died on 10 November 1938, profoundly mourned by his people then and revered by them still as the father of their country.

At the time of the establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1923, the Anatolian city of Ankara was chosen as the capital and the seat of parliament. Soon afterwards the embassies of the great European powers packed up and moved to new quarters in Ankara, leaving their old mansions along the Grand Rue de Pera in Istanbul. And so, for the first time in 16 centuries, Istanbul was no longer the capital of an empire. Now, more than eight decades later, history would seem to have passed Istanbul by, and no longer do wealthy and powerful emperors adorn her with splendid buildings. The old town is now running down at the heels, some say, living on her memories. But what memories they are!

Many monuments of the city’s imperial past can be seen from the Galata Bridge, particularly those which stand on the six hills along the Golden Horn. On the First Hill, the ancient acropolis of Byzantium, we see the gardens and pavilions of Topkap

ı

Saray

ı

and the great dome of Haghia Sophia, framed by its four minarets. The most prominent monument on the Second Hill is the baroque Nuruosmaniye Camii, while the Third Hill is crowned by the Süleymaniye, surrounded by the clustering domes of its pious foundations. On the foreshore between these two hills we see Yeni Cami, the large mosque which stands at the Stamboul end of the Galata Bridge, and Rüstem Pa

ş

a Camii, the smaller mosque which is located in the market district just to the west. The Third and Fourth Hills are joined by the Roman aqueduct of Valens; but to see this we must bestir ourselves from our seat on the Galata Bridge and walk some distance up the Golden Horn towards the inner span, the Atatürk Bridge. The Fourth Hill is surmounted by Fatih Camii, the Mosque of the Conqueror, whose domes and minarets can be seen in the middle distance, some way in from the Golden Horn. The mosque of Sultan Selim I stands above the Golden Horn on the Fifth Hill. Far off in the distance we can just see the minarets of Mihrimah Camii, which stands on the summit of the Sixth Hill, a mile inland from the Golden Horn and just inside the Theodosian walls. Across the Golden Horn the skyline is dominated by the huge, conical-capped Galata Tower, the last remnant of the medieval Genoese town of Galata.

Looking down the Golden Horn to where it joins the Bosphorus and flows into the Marmara we see the fabled Maiden’s Tower, the little islet watchtower which stands at the confluence of the city’s garland of waters. Beyond, on the Asian shore, the afternoon sun is reflected in the windows of Üsküdar, anciently called Chrysopolis, the City of Gold. Farther to the south, out of sight from our vantage point on the Galata Bridge, is the Anatolian suburb of Kad

ı

köy, the ancient Chalcedon, settled a decade or so before Byzantium. Sipping our tea or rak

ı

in our café on the Galata Bridge, we rest our eyes once more on the gray and ruined beauty of Stamboul, crowned with imperial monuments on its seven ancient hills. At times like this we can agree with the Delphic oracle, for those who settled across the straits from this enchanting place were surely blind.

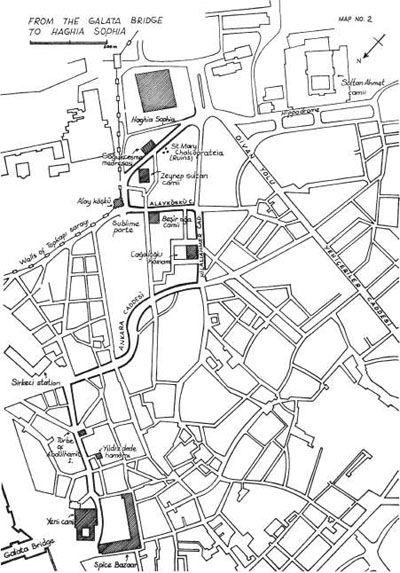

Galata Bridge

to Haghia Sophia

The area around the Stamboul end of the Galata Bridge, known as Eminönü, is the focal point of Istanbul’s colourful and turbulent daily life. Throughout the day and early evening a steady stream of pedestrians and traffic pours across the bridge and along the highway that parallels the right bank of the Golden Horn, while an endless succession of ferry-boats sail to and from their piers around and under the Galata Bridge, connecting the centre of the city to its maritime suburbs on the Bosphorus, the Marmara and the Princes’ Isles, as well as to stops on both shores of the Golden Horn itself.

The quarter now known as Eminönü was during the latter period of the Byzantine Empire given over to various Italian city-states, some of which had obtained trading concessions here as early as the end of the tenth century. The area to the right of the Galata Bridge, where the markets are located, was the territory of the Venetians. The region immediately to the left of the bridge was given over to the Amalfians, and beyond them were the concessions of the Pisans and the Genoese, who also had extensive concessions across the Golden Horn in Galata. These rapacious Italians were as often as not at war with one another or with the Byzantines, though at the very end they fought valiantly at the side of the Greeks in the last defence of the city. After the Conquest the concessions of these Italian cities were effectively ended in Stamboul, although the Genoese in Galata continued to have a measure of autonomy for a century or so. Today there is virtually nothing left in Eminönü to remind us of the colourful Latin period in the city’s history, other than a few medieval Venetian basements underlying some of the old hans in the market quarter around Rüstem Pa

ş

a Camii.

The area directly in front of the Galata Bridge, where Yeni Cami now stands, was in earlier centuries a Jewish quarter, wedged in between the concessions of the Venetians and the Amalfians. The Jews who resided here were members of the schismatic Karaite sect, who broke off from the main body of Orthodox Jewry in the eighth century. The Karaites seem to have established themselves on this site as early as the tenth century, at about the time when the Italians first obtained their concessions here. The Karaites outlasted the Italians though, for they retained their quarter up until the year 1660, at which time they were evicted to make room for the final construction of Yeni Cami. They were then resettled in the village of Hasköy some three kilometres up the Golden Horn and on its opposite shore, where their descendants remain to this day.

YEN

İ

CAM

İ

The whole area around the Stamboul end of the Galata Bridge is dominated by the imposing mass of Yeni Cami, the New Mosque, more correctly called the New Mosque of the Valide Sultan. The city is not showing off its great age in calling new a mosque built in the seventeenth century: it is just that the present mosque is a reconstruction of an earlier mosque of the same name. The first mosque was commissioned in 1597 by the Valide Sultan (Queen Mother) Safiye, the mother of Sultan Mehmet III. The original architect was Davut A

ğ

a, a pupil of the great Sinan, the architect who built most of the finest mosques in the city during the golden age of Süleyman the Magnificent and his immediate successors. Davut A

ğ

a died in 1599, however, and was replaced by Dalg

ı

ç Ahmet Çavu

ş

, who supervised the construction up until the year 1603. But in that year Mehmet III died and his mother Safiye was unable to finish her mosque. For more than half-a-century the partially completed mosque stood on the shore of the Golden Horn, gradually falling into ruins. Then in 1660 the whole area was devastated by fire, further adding to the ruination of the mosque. Later in that year the ruined and fire-blackened mosque caught the eye of the Valide Sultan Turhan Hadice, mother of Mehmet IV, who decided to rebuild it as an act of piety. The architect Mustafa A

ğ

a was placed in charge of the reconstruction, which was completed in 1663. On 6 November of that year the New Mosque of the Valide Sultan was consecrated in a public ceremony presided over by the Sultan and his mother. The French scholar Grelot, writing when Turhan Hadice was still alive, tells us that she was one of the “greatest and most brilliant (

spirituelle

) ladies who ever entered the Saray,” and that it was fitting that “she should leave to posterity a jewel of Ottoman architecture to serve as an eternal monument to her generous enterprises.”