Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (3 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

Two works of a very different nature are frequently referred to: the so-called

Tezkeret-ül Ebniye

or

List of Buildings

by the great architect Sinan, drawn up soon after his death in 1588 by his friend the poet Mustafa Sa’i; and the

Hadikat-ül Cevami

or

Gardens of the Mosques

by Haf

ı

z Hüseyin Ayvansaray

ı

, which is an account of all the mosques extant in Istanbul in his time (about 1780). Of modern guidebooks only two are of value: Ernest Mamboury,

Istanbul Touristique

(2nd ed. 1950), a pioneer work by a scholar of distinction; and Semavi Eyice,

Petit Guide a travers les Monuments Byzantines et Turcs

(1953), an invaluable little book by the leading Turkish authority on the city, prepared for the Third Congress of Byzantine Studies and never on public sale. But our work is based on a wide acquaintance with the authorities ancient and modern, Turkish and foreign; unfortunately a guidebook is not the place for detailed references and acknowledgements.

To our editors at the Redhouse Press, William Edmonds, C. Robert Avery and Robert Arndt, we owe more than an author’s usual debt to his publisher. If this book is reasonably free from the tiresome errors of the press which often abound in English works published in foreign countries, the credit is almost wholly due to their skill and patience. We wish particularly to thank William Edmonds, for without his constant help and unremitting zeal it would not have been possible to pro duce this guide.

Our more personal debts are many. The elder collaborator remembers with delight and gratitude his first introduction to the antiquities of the city by two former colleagues on the staff of Robert College, the late Sven Larsen and Mr. Arthur Stratton, who has recently poured his enthusiasm for the city into his book about Sinan. The late Paul Underwood and his colleague Mr. Ernest Hawkins allowed him to follow their wonderful work of restoration at Kariye Camii as it progressed. Mr. Robert Van Nice not only allowed him the same privilege throughout his long years of investigations at Haghia Sophia but was a constant source of help and encouragement, as was also Mr. Cyril Mango who introduced him to many an important traveller of former days. To Dr. Aptullah Kuran, his former student at Robert College, later his colleague there, and the first rector at the University of the Bosphorus, most penetrating of Turkish historians of Ottoman architecture, his debts are too continuous and multifarious to be easily acknowledged or adequately repaid. And the same is true of Mr. Godfrey Goodwin, until recently professor of art history at Robert College, whose monumental

History of Ottoman Architecture

has revealed to the world for the first time in a western language the wealth and variety of its subject.

The younger author also owes a debt of gratitude to Godfrey Goodwin, who tried to teach him something of Byzantine and Ottoman architecture and who was his first companion-guide to the antiquities of Istanbul. The author fondly recalls the many friends who shared with him and his wife Dolores the pleasures of strolling through Istanbul on Saturday afternoons, picnicking on a Bosphorus ferry or on a tower of the Theodosian walls and later singing and dancing together at one of the now-vanished

tavernas

of old Pera. To list their names would be too poignant, since so many have left Istanbul and some he will never see again; he can only hope that this book will evoke for his dear friends some memories of the mad and happy days we spent together in this wonderful old town.

In the memorial dedication we have expressed our sense of gratitude to three of our dearest and most lamented colleagues. Lee Fonger, for many years Librarian of Robert College, not only made the College’s unrivalled collection of books on the Near East easily available to us but did his best to supply us with whatever material was needed. Keith Greenwood, whose history of the founding and early years of Robert College still awaits publication, was a source of encyclopedic information and enthusiastic support. Their untimely deaths, and that of our very good friend David Garwood, deprived the College community of three of its most vital and creative men; for some of us Istanbul will never be the same without them. Our dedication of this book extends also to their wives, Carol Fonger, Joanne Greenwood and Mini Garwood, and to Dolores Freely, for they have been our companions on so many strolls through Istanbul across the years.

H.S.-B.

J.F.

Bosphorus University

June 1972

from the Bridge

A poet writing 14 centuries ago described this city as being surrounded by a garland of waters. Much has changed since then, but modern Istanbul still owes much of its spirit and beauty to the waters which bound and divide it. There is perhaps nowhere else in town where one can appreciate this more than from the Galata Bridge, where all tours of the city should begin. There are other places in Istanbul with more panoramic views, but none where one can better sense the intimacy which this city has with the sea, nor better understand how its maritime situation has influenced its character and its history. So the visitor is advised to stroll to the Galata Bridge for his first view of the city. But you should do your sight-seeing there as do the Stamboullus, seated at a teahouse or café on the lower level of the Bridge, enjoying your

keyif

over a cup of tea or a glass of rak

ı

, looking out along the Golden Horn to where it meets the Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmara.

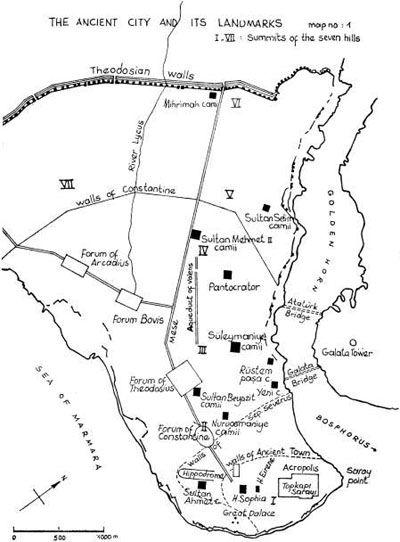

Istanbul is the only city in the world which stands upon two continents. The main part of the city, which is located at the south-eastern tip of Europe, is separated from its suburbs in Asia by the incomparable Bosphorus. The Golden Horn then divides the European city into two parts, the old imperial town of Stamboul on the right bank and the port quarter of Galata on the left, with the more modern residential districts on the hills above Galata and along the European shore of the lower Bosphorus. Stamboul itself forms a more or less triangular promontory bounded on the north by the Golden Horn and on the south by the Sea of Marmara, the ancient Propontus. At Saray Point, the apex of this promontory, the Bosphorus and the Golden Horn flow together into the Marmara, forming a site of great beauty. So it must have appeared to Jason and the Argonauts when they sailed across the Propontus 3,000 years ago in search of the Golden Fleece, and so it still appears today to the tourist approaching the city on a modern oceanliner.

According to tradition, the original settlement from which the city grew was established on the acropolis above Saray Point in the seventh century B.C., although there is evidence that the site was inhabited much earlier than that. The legendary founder of the town of Byzantium was Byzas the Megarian, who established a colony on the acropolis in the year 667 B.C. We are told that Byzas had consulted the Delphic oracle, who advised him to settle “opposite the land of the blind”. The oracle was referring to the residents of Chalcedon, a Greek colony which had been established some years before across the strait. The implication is that the Chalcedonians must have been blind not to have appreciated the much greater advantages of the site chosen by Byzas. Situated at the mouth of the Bosphorus, it was in a position to control all shipping from the Black Sea, the ancient Pontus, through to the Propontus and the Aegean, while its position on the boundary of Europe and Asia eventually attracted to it the great land routes of both continents. Moreover, surrounded as it is on three sides by water, its short landward exposure defended by strong walls, it could be made impregnable to attack. As the French writer Gyllius concluded four centuries ago: “It seems to me that while other cities may be mortal, this one will remain as long as there are men on earth.”

From the very beginning of its history Byzantium was an important centre for trade and commerce, and was noted for its wine and fisheries. Not all of the wine was exported, apparently, for in antiquity the citizens of Byzantium had the reputation of being confirmed tipplers. Menander, in his comedy,

The Flute Girl

, tells us that Byzantium makes all of her merchants sots. Says one of the Byzantine characters in his play: “I booze it all the night, and upon my waking after my dose I feel that I have no less than three heads upon my shoulders.” The character of a city is formed quite early in its career.

During its first millennium Byzantium had much the same history as the other Greek cities in and on the edge of Asia Minor. The city was taken by Darius in the year 512 B.C., and remained under Persian control until 479 B.C., when it was recaptured by the Spartan general Pausanias. Byzantium later became part of the Athenian Empire; although it revolted in 440 B.C. and again in 411 B.C., it was conquered on each occasion by the Athenians, the last time by Alcibiades. After the defeat of Athens in 403 B.C. Byzantium was captured by Lysander and was still under a Spartan governor when Xenophon’s Ten Thousand arrived shortly afterwards. Xenophon and his men were so inhospitably treated that in retaliation they occupied the town, leaving only after they exacted a large bribe from its citizens. During the first half of the fourth century B.C. Byzantium was held in enforced alliance with Athens, but in the year 356 B.C. the city rebelled and won its independence. Despite this the Athenians, through the urgings of Demosthenes, sent aid to Byzantium when it was besieged by Philip of Macedon in 340 B.C. A contemporary Athenian writer informs us that the Byzantine commanders were forced to build taverns within the very defence walls in order to keep their tipsy soldiers at their posts. But the Byzantines fought well, for they successfully held off the Macedonians in a memorable siege.

Despite their spirited fight against King Philip, the Byzantines had enough good sense not to resist his son, Alexander the Great. Soon after Alexander’s victory at the battle of the Granicus in 334 B.C. Byzantium capitulated and opened its gates to the Macedonians. Later, after Alexander’s death in 323 B.C., Byzantium was involved in the collapse and dismemberment of his empire and the subsequent eastward expansion of Rome. In the year 179 B.C. the city was captured by the combined forces of Rhodes, Pergamum and Bithynia. A century later Byzantium was a pawn in the struggle between Rome and Mithridates, King of Pontus. After the final victory of Rome, Byzantium became its client state, and thereafter enjoyed nearly three centuries of quiet prosperity under the mantle of the Pax Romana. But eventually, in the closing years of the second century A.D., Byzantium was swept up once again in the tides of history. At that time Byzantium found itself on the losing side in a civil war and was besieged by the Emperor Septimius Severus. After finally taking Byzantium in the year 196 A.D., the Emperor tore down the city walls, massacred the soldiers and officials who had opposed him, and left the town a smouldering ruin. A few years afterwards, however, Septimius realized the imprudence of leaving so strategic a site undefended and then rebuilt the city and its walls. The walls of Septimius Severus are thought to have begun at the Golden Horn a short distance downstream from the present site of the Galata Bridge, and to have ended at the Marmara somewhere near where the lighthouse now stands. The area thus enclosed was more than double that of the ancient town of Byzantium, which had comprised little more than the acropolis itself.

At the beginning of the fourth century A.D. Byzantium was profoundly affected by the climactic events then taking place in the Roman Empire. After the retirement of the Emperor Diocletian in the year 305, his successors in the Tetrarchy, the two co-emperors and their Caesars, fought bitterly with one another for the control of the Empire. This struggle was eventually won by Constantine, Emperor of the West, who in the year 324 finally defeated Licinius, Emperor of the East. The last battle took place in the hills above Chrysopolis, just across the Bosphorus from Byzantium. On the following day, 18 September in the year A.D. 324, Byzantium surrendered and opened its gates to Constantine, now sole ruler of the Roman Empire.