Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (66 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

We now arrive at the great square in Karaköy, where all the streets of Galata converge chaotically towards the bridge. There is more of Galata yet to see, along the European shore of the lower Bosphorus, but perhaps we should pause here and leave the rest for our next tour. And besides, whenever one is in this area one is always tempted to relax at a café or restaurant on the lower level of the bridge. From there one can observe how the sometimes golden light of late afternoon gives even Galata a brief and spurious beauty. Then, as the sun sets behind Stamboul, silhouetting the domes and minarets of the imperial mosques on the skyline of the old city, the polluted waters of the Golden Horn do indeed look like molten gold.

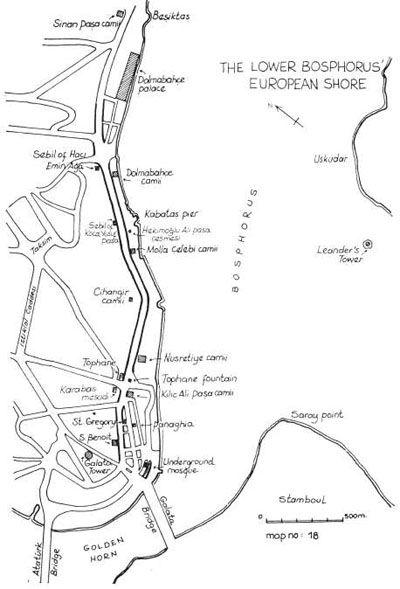

European Shore

We will begin this tour where the last one ended, at the Karaköy end of the Galata Bridge. There are few monuments of great importance along this stretch; nevertheless it makes a pleasant and interesting stroll.

Before we begin, we might say a word or two about the Galata Bridge, where we have begun or ended so many of our strolls through Istanbul. The present bridge was completed in 1992, replacing an earlier bridge dating from 1910, which now rests unused between Ayvansaray and Hasköy. The central section of the bridge opens at four o’clock each morning to permit the passage of shipping to that part of the Golden Horn between the two bridges. (It is also opened occasionally at times of civic disturbance to isolate Stamboul from the rest of the city.) The first bridge at this point was built in 1845 by Bezmialem Valide Sultan, mother of Sultan Abdül Mecit; it was of wooden construction and quite pretty, as we see from the old prints.

YERALTI CAM

İ

Leaving Karaköy we begin walking along the seaside road, which is always bustling with pedestrians rushing to and from the ferry station. About 200 metres along, past the ferry pier, we turn left and then left again at the next street. A short way along on our right we come to the obscure entrance to Yeralt

ı

Cami, the Underground Mosque. This is a strange and sinister place. The mosque is housed in the low, vaulted cellar or keep of a Byzantine tower or castle which is probably to be identified with the Castle of Galata. This was the place where was fastened one end of the chain which closed the mouth of the Golden Horn in times of siege. Descending into the mosque, we find ourselves in a maze of dark, narrow passages between a forest of squat passages supporting low vaults, six rows of nine or 54 in all. Towards the rear of the mosque we find the tombs of two sainted martyrs, Abu Sufyan and Amiri Wahabi, both of whom are supposed to have died in the first Arab siege of the city in the seventh century. Their graves were revealed to a Nak

ş

ibendi dervish in a dream in 1640, whereupon Sultan Murat IV constructed a shrine on the site. Then in 1757 the whole dungeon was converted into a mosque by the Grand Vezir Kö

ş

e Mustafa Pa

ş

a.

CHURCH AND L

İ

SE OF ST. BENO

İ

T

Walking northward to Kemeralt

ı

Caddesi, we see on the far side of the avenue a tall medieval tower. This is all that remains of the fifteenth-century church of St. Benoit. This church was founded by the Benedictines in 1427 and later became the chapel of the French ambassadors to the Sublime Porte, several of whom are buried there. After being occupied by the Jesuits for several centuries, it was given on the temporary dissolution of that order in 1773 to the Lazarists, to whom it still belongs. In 1804 they established a school here which is still ones of the best of the foreign lises in the city. Apart from its original tower, the present church dates partly from 1732 (the nave and south aisle) and partly from 1871 (the north aisle).

CHURCH OF ST. GREGORY

Somewhat farther along the avenue and on the opposite side of the avenue stands the Armenian church of St. Gregory the Illuminator (Surp Kirkor Lusavoriç). This was erected in 1958 after the original church nearby had been demolished when the avenue was widened. The new building is interesting as a replica of the famous church at Echmiadzin, built in the seventh century and one of the masterpieces of ancient Armenian architecture. The older church which was pulled down was an early nineteenth-century structure of no great architectural interest, but it contained some unusual tiles from the Tekfur Saray kilns; these have been transferred to the crypt of the present church.

Galata is a town of surprises and in particular shelters a large number of Christian and other sects. For instance, if you go down the alley in front of Surp Kirkor and wander about in the rather mean streets between it and the sea, you will find three churches that originally belonged to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate but which are now the property of the so-called Turkish Orthodox Church. The latter was founded in 1924 by a dissident priest from Anatolia named Papa Eftim, who took control of the three churches in Galata and set up his own church for his parishioners, in which the mass is said in Turkish rather than Greek. Papa Eftim, who styled himself Patriarch Efthemios I, engaged in a running battle with the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate that at one point reached the League of Nations. After his death he was succeeded as patriarch by his two sons in turn, but by now the congregation is virtually non-existent, though the three churches in Galata – St. John, St. Nicholas and the Panaghia (Virgin) Kafatiani – still belong to the Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate such as it is. The Panaghia Kafatiani, the oldest of the three churches, founded in 1475 by Greeks from Kaffa in the Crimea, though the present church dates only from 1840, is the patriarchate of the Turkish Orthodox Church; it preserves a sacred icon of the Virgin Hodegitria brought from the Crimea by the original parishioners.

We now come to the district of Tophane, just outside the old walls of Galata; it takes its name from the cannon foundry which still dominates the road on the left-hand side. There was once a small but busy and picturesque port here; this has now been largely filled in, but there are still several Ottoman buildings of some interest in the immediate vicinity.

The first monument one comes to, on the right, is the mosque complex which Sinan built in 1580 for K

ı

l

ı

ç Ali Pa

ş

a. This Ali was an Italian from Calabria called Ochiali who had become a Muslim and risen high in the Ottoman navy, being among the few officers who distinguished himself at the disastrous battle of Lepanto in 1571. As a reward for his outstanding service Selim II appointed him Kaptan Pa

ş

a, that is, Lord High Admiral, and conferred upon him the name K

ı

l

ı

ç, the Sword. He twice captured Tunis from the Spaniards, the second time permanently. When he died in 1587, his fortune was estimated at 500,000 ducats. “Although ninety years of age,” says von Hammer, “he had not been able to renounce the pleasures of the harem, and he died in the arms of a concubine.”

To return to the mosque. Profoundly as Sinan had been impressed and inspired by Haghia Sophia, he had always avoided any kind of direct imitation of that great building. Now in his old age – he was over 90 when he designed this mosque – whether for his own amusement or on instructions from K

ı

l

ı

ç Ali Pa

ş

a cannot be known – he deliberately planned a structure which is practically a small replica of the Great Church. It is one of his least successful buildings. One does not know quite why this is; it must have something to do with the greatly reduced proportions. But the fact is that the building seems heavy, squat and dark; it is not improved by the plethora of lamps, but this, of course, is not Sinan’s fault. His main departures from the plan of Haghia Sophia are: the provision of only two columns instead of four between each of the piers to north and south, and the suppression of the exedrae at the east and west ends; both seem to have been dictated by the reduced scale, and indeed to have retained the original disposition would clearly have made the building even heavier and darker. Nevertheless, the absence of the exedrae deprives the mosque of what in Haghia Sophia is one of its main beauties. The mihrab is in a square projecting apse, where there are some Iznik tiles of the best period. At the west there is a kind of pseudo-narthex of five cross-vaulted bays separated from the prayer area by four rectangular pillars.

The mosque is preceded by a very picturesque double porch. The inner one is of the usual type, five domed bays supported by columns with stalactited capitals; over the entrance portal is the historical inscription giving the date A.H. 988 (A.D. 1580), and above this a Kuranic text in a fascinating calligraphy and set in a curious projecting marble frame, triangular in shape and adorned with stalactites. The outer porch has a steeply sloping penthouse roof, supported by 12 columns on the west façade and three on each side, all with lozenge capitals; in the centre is a monumental portal of marble, and there are bronze grilles between the columns; the whole effect being quite charming.

The külliye of K

ı

l

ı

ç Ali Pa

ş

a is extensive, including a türbe, a medrese and a hamam. The türbe is in the pretty graveyard behind the mosque; it is a plain but elegant octagonal building with alternately one and two windows in each façade, in two tiers. The medrese, opposite the south-east corner of the mosque, is almost square and like the mosque itself a little squat and shut in; it may well not be by Sinan since it does not appear in the

Tezkeret-ül Ebniye.

It is now used as a clinic. The hamam just in front of the medrese is single; unfortunately it is no longer in use. The plan is unique among the extant hamams of Sinan. The vast camekân doors lead into two separate so

ğ

ukluks lying not between the camekân and the hararet, as is habitual, but on either side of the latter; each consists of three domed rooms of different sizes. From that on the right a passage leads off to the lavatories; the rooms on the opposite side were used as semi-private bathing cubicles. The hararet itself, instead of having the usual cruciform plan, is hexagonal with open bathing places in four of its six arched recesses, the other two giving access from the two so

ğ

ukluks. The plan is an interesting variation on the standard, and it has been pointed out that broadly similar plans may be found in one or two of the older hamams at Bursa.

Across the street north of K

ı

l

ı

ç Ali Pa

ş

a Camii is one of the most famous of the baroque fountains, known as Tophane Çe

ş

mesi. Built in 1732 by Mahmut I, it has marble walls completely covered with floral designs and arabesques carved in low relief and originally painted and gilded. Its charming domed and widely overhanging roof was lacking for many years but has recently been restored. The fountain with the mosque beside it and the busy and picturesque throngs around the port used to be a favourite subject with etchers of the eighteenth and nineteenth century.