Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (68 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

The palace is built on a site famous in history as that from which began the astonishing journey overland of some 70 ships of Fatih Mehmet’s fleet on 22 April 1453; up the hill to Pera they were drawn on wheeled platforms and down the valley of Kas

ı

m Pa

ş

a to the Golden Horn, thus bypassing the insuperable obstacle of the chain which barred its mouth. After Fatih’s time the area became a royal garden; Evliya says that Selim I built a kiosk here, and in Gyllius’ time it was known as the Little Valley of the Royal Garden

(Vallicula Regii Horti).

It was Ahmet I who began to fill in the small harbour in order to extend his gardens, and the filling-in process was continued by his son Osman II. As Evliya writes: “By order of Sultan Osman II all ships of the fleet, and all merchant ships at that time in the harbour of Constantinople, were obliged to load with stones, which were thrown into the sea before Dolmabahçe, so that a space of 400 yards was filled up with stones where the sea formed a bay, and the place was called ‘the filled-up garden,’ or Dolmabahçe.”

Evliya goes on to tell one of his astonishing stories about his unpredictable friend, Murat IV: “Sultan Murat IV happened once to be reading at Dolmabahçe the satirical work

Sohami

of Nefii Efendi, when the lightning struck the ground near him; being terrified he threw the book into the sea, and then gave orders to Bayram Pa

ş

a to strangle the author Nefii Efendi.”

And on that mad note we will end our tour. We might then retrace our steps to the square before Dolmabahçe; from there we can return to Taksim along the Ayazpa

ş

a road, which winds uphill to the left of the football stadium.

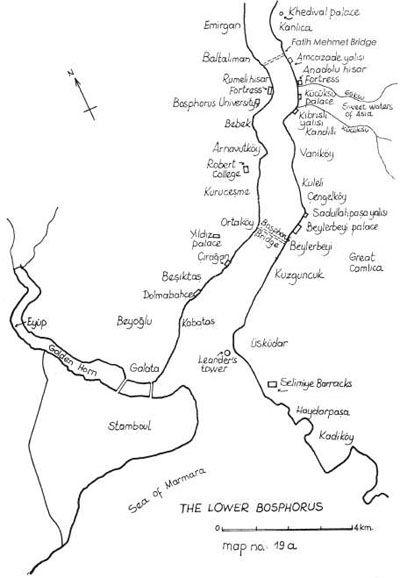

We will begin our final tour of Istanbul where we began our first, at the Galata Bridge, where we will board a ferry to sail up the Bosphorus. Here we have saved the best for last, for the Bosphorus and its shores are by far the most beautiful part of Istanbul.

The history of the Bosphorus begins with the “Inachean daughter, beloved of Zeus” Io, who was turned into a heifer to conceal her from Hera. Pursued by the jealous Hera’s gadfly, Io plunged into the waters that separate Europe from Asia and bequeathed them the name by which they have ever since been known, Bosphorus, or Ford of the Cow. The next event in Bosphoric history is the passage of the Argonauts on their way to seek the Golden Fleece in Colchis at the far end of the Black Sea. On our own journey up the Bosphorus we will stop at several places which ancient and local tradition associated with Jason and his fabulous crew.

The first fully historic event connected with the Bosphorus is the passage across it in 512 B.C. of the huge army which Darius led against the Scythians. From that time onward it played an important and even decisive role in the history of the city erected at its southern extremity in 667 B.C.; for, as Gyllius eloquently points out, the Bosphorus is “the first creator of Byzantium greater and more important than Byzas, the founder of the City.” And he later sums up the predominant importance of this “Strait that Purpasses all straits” by the epigram: “The Bosphorus with one key opens and closes two worlds, two seas.”

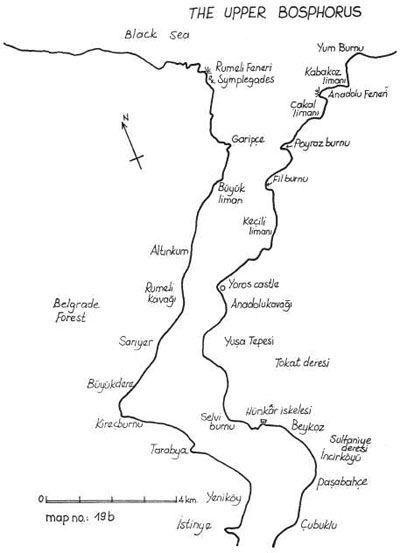

The Bosphorus is a strait some 30 kilometres long, running in the general direction north-north-east to south-south-west, and varying greatly in width from about 700 metres at its narrowest to over 3.5 kilometres at its widest. Its average depth at the centre of the channel is between 50 and 75 metres, but at one point it reaches a depth of over 100 metres. The predominant surface current flows at a rate of three to five kilometres per hour from the Black Sea to the Marmara, but, because of the sinuosity of the channel, eddies producing strong reverse currents occupy most of the indentations of the shore. A very strong wind may reverse the main surface current and make it flow north, in which case the counter eddies also change their direction. At a depth of about 40 metres there is a subsurface current, called

kanal

in Turkish, which flows from the Marmara north towards the Black Sea. Its waters, however, are for the most part prevented from entering the Black Sea by a threshold just beyond the mouth of the Bosphorus; these lower waters, denser and more saline than the upper, are turned back by the threshold, mingle with the upper waters, and are driven back towards the Marmara with the surface current. The lower current is strong enough so that under certain conditions, if fishing nets are lowered into it, it may pull the boats northward against the southerly surface current.

The casual visitor to Istanbul, especially if one comes in summer, might find it difficult to believe that the Bosphorus can be a perverse and dangerous body of water. Seen from the hills along its shore as it curves and widens and narrows, it often looks like a great lake or series of lakes; while its rapid flow from the Black Sea to the Marmara gives it something of the character of a river. Yet anyone who has observed its erratic currents and counter-currents, the various winds that encourage or hinder navigation, the impenetrable fogs that envelop it, even occasionally the icebergs that choke it, will realize that it is indeed a part of the ungovernable sea. Here Belisarius fought the invincible whale Poryphyry, that Moby Dick that wrecked all shipping; here Gyllius observed the largest shark he had ever seen; while even now one still sees schools of dolphins sporting in its waves. Since it is an international waterway, the Bosphorus is busy day and night with a traffic of cargo ships, oil-tankers and ocean-liners, as well as with the local and more colourful ferries and fishing boats. The frequent sharp and unexpected bends in the straits, the tricky currents and occasional storms and dense fogs can make the passage quite difficult at times. Nearly every year large ships collide with one another on the Bosphorus or run aground on its banks, smashing into the houses along its shores. Old Bosphorus-dwellers will regale you with tales of having been awakened from their slumbers by a terrific crash, to find their home tumbled in wreckage about them and the rusty prow of a tramp steamer protruding into the library; or of how a quiet supper was suddenly disrupted when the yardarm of a passing schooner smashed through the dining-room window and swept the table clear.

Both shores of the Bosphorus are indented by frequent bays and harbours, and in general it will be found that an indentation on one shore corresponds to a cape or promontory on the other. Most of the bays are at the mouths of valleys reaching back into the hills on either side, and a great many of the valleys have streams that flow into the Bosphorus. Almost all of these are insignificant; only the Sweet Waters of Europe and the Sweet Waters of Asia have any claim to be called rivers, and these are quite small. Both shores are lined with hills, none of them very high, the most imposing being the Great Çaml

ı

ca (267 metres) and Yu

ş

a Tepesi (201 metres), both on the Asian side; nevertheless, especially on the upper Bosphorus, the hills often seem much higher than they are because of the way in which they come down in precipitous cliffs into the sea. In spite of the almost continuous villages and the not infrequent forest fires, both sides are well-wooded, especially with cypresses, umbrella-pines, plane-trees, horse-chestnuts, terebinths and Judas-trees. The red blossoms of the latter in spring, mingled with the mauve flowers of the ubiquitous wisteria, and the red and white candles of the chestnuts, pervaded by the songs of nightingales and blackbirds, give the Bosphorus at that season an even more superlative beauty.

Let these general observations suffice, and let us now explore this most fascinating strait in more detail from the deck of a Bosphorus ferry. But Bosphorus ferries are whimsical boats, flitting back and forth between the continents without apparent reason. And so our description will have to be a somewhat idealized one, which assumes that we sail up the European side of the strait and down the Asian, stopping where we please along the way.

The first village (though now part of the city) on the European shore of the lower Bosphorus is at Be

ş

ikta

ş

, a short distance beyond the Palace of Dolmabahçe, which we visited on our last stroll. Various explanations have been advanced for the name Be

ş

ikta

ş

, or Cradle Stone, the most probable being that it is a Turkish adaptation of the Greek name, Diplokionion, the Twin Columns, from two lofty columns of Theban granite which stood near the shore. In Byzantine times there was a famous church of St. Mamas here, a port, a royal palace and a hippodrome. These have vanished without a trace, but there are still two or three Ottoman monuments of some interest.

The first of these is the türbe of another great pirate-admiral of the Golden Age, the famous Hayrettin Pa

ş

a. This is one of the earliest works of Sinan, dated by an inscription over the door to A.H. 948 (A.D. 1541–2). The structure is octagonal, with two rows of windows. The upper row has recently been filled in with stained glass; and the dome has been rather well-repainted with white arabesques on a rust-coloured ground. Three catafalques occupy the centre of the türbe, and in the little garden outside is a cluster of handsome sarcophagi.

Hayrettin Pa

ş

a, better known in the West as Barbarossa, died in 1546 and on the fourth centennial of his death a statue was unveiled to his memory in the square facing his tomb. It is by far the best public statue in the city, a vivid and lively work by the sculptor Zühtü Mürido

ğ

lu. On the back are six verses by the poet Yahya Kemal which may be translated thus:

Whence on the sea’s horizon comes that roar?

Can it be Barbarossa now returning

From Tunis or Algiers or from the Isles?

Two hundred vessels ride upon the waves,

Coming from lands the rising Crescent lights:

O blessed ships, from what seas are ye come?