Stuffed (20 page)

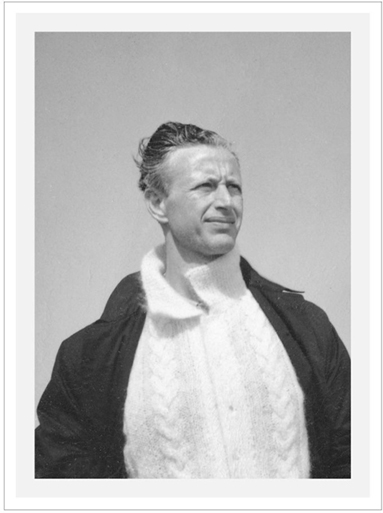

Josef Morgenbesser

Brunek Morgenbesser

Nella Morgenbesser

The enduring image of someone you’ve loved is not necessarily your choice. It took fourteen years, but now when I think of Hank, I don’t see his face in a hospital bed. I see him coming down a mountain. It was easy to spot him. Not because of his bright red ski suit with the white armbands or his yellow jumpsuit with the matching yellow boots. What set Hank apart was the way he skied. The top half of his body stayed still. His hips barely shifted. He looked as if he were dancing down the mountain—a sophisticated dancer, the kind who feels the music and conveys that using only the most economical gestures. Hank skied a way nobody else did. Even on a packed slope, you could pick him out. And that’s how I can see him now, skiing and smiling, skiing to take your breath away. Hank made it look easy. I think he was a natural.

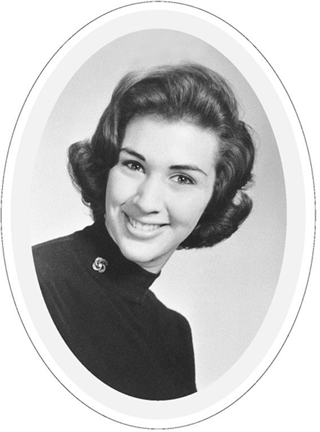

My gorgeous big sister

SCRAMBLED EGGS

I’ve flown to Florida to take care of my best friend, the person who sees herself as always taking care of me, my big sister. I dial up from the hotel lobby.

“Don’t be scared,” she says.

“I can’t wait to see you.”

“Room three seventeen.” She hangs up the phone.

I ride the elevator carbonated with expectation. What?

What?

The other two face-lifts I’ve seen had some mileage on them. My sister’s face-lift is in its second day.

I knock. “Let me in, whee-oop!”

The door opens a crack. A hand snakes around. I know those fingers! I recognize those freckles! I know those squared red nails!

The door inches.

“Just open it,” I say.

She does.

If someone fell from the top of the Empire State Building and landed on their nose, it couldn’t be worse. I search the face for something that says I definitely have the right room. Luckily, my sister is wearing her old Victoria’s Secret pajamas.

“I’m so glad you’re here.” She weeps.

“Wow!” I say.

“I

had

to do it.” Tears flow from what used to be her eyes. “I haven’t been able to look at my face while I brush my teeth for a

year.

Come.” She shuffles toward the bed. With enormous effort my sister feels backward for the edge, sits, then swings her legs over until she can lean against the pillows. She does this like a Balinese dancer, without changing the flex of her chin. “Put your fingers on what’s been done and tell me

everything.

” She lies there waiting. “I can’t

seeeeeeee.

”

I examine what used to be my gorgeous big sister. I put a fingertip on the ventral side of her chin and run it side to side, an inch and a half. It’s prickly. “There are stitches here,” I say.

I look her over, then pat along her upper eyelids. Her eyes, her big brown eyes that danced when she smiled, are slits tilted at forty-five degrees. They are sewn partially shut. The micro-opening looks like a split seam. It is completely filled by brown eyeball, like something that lives underground. I trace the corners of her eyes where the thorny black stitches stick out. Then I finger her ears all the way around. The stitches make it look as if they’ve been cut off then sewn back on. There are hundreds of these tiny threads inside her ears too. They look like the almost invisible black trico flies I use to catch trout.

In her head, like croquet wickets, are rows of metal staples.

“These are staples.” I drum my fingers all over her scalp. “And these are stitches.”

“What about the screws?” she says.

I find those too.

“What about my

neck

?”

“It looks gajus,” I say. “You’re down to one chin.”

“No. I mean

this.

”

We explore where the drain enters behind her ear. It’s threaded down and inside, embossing her neck. The drain looks like a subcutaneous choker. A bloody liquid drips from the exposed part into a clear plastic bulb. Her upper lip, which has been derm-abraded to remove tiny vertical lines that used to wick lipstick, is oozing a thick yellow mustache. Because of the derm-abrasion, her lip is so swollen her words come out muffled.

“I think he did a really good job,” I say. “The stitches are so neat.”

I put fresh ice cubes and water in the small bowl beside her bed. She tells me how to ice her, two folded gauze pads on her eyes and cheeks and one unfolded flat across her forehead. Ice rolled in a towel on her neck.

“There’s stuff on your tray,” I say.

“You eat it.”

The frittata is cold, so is the toast.

“Sure you don’t want some?”

“Can’t

chew.

” She starts to cry again. “I don’t know why I’m so

weepy,

” she says. “It must be the

anesthesia.

It took

eight hours.

”

My sister looks terrifying, and I don’t know what to do. She reaches for the envelope with the pictures she’d shown the doctor.

“I want to look like this,” she’d told him, fanning out photos from 1971.

“You will,” he’d promised.

I want to be in water,” my sister says through tears. I run her a warm tub. “Put some of that bath stuff in.” She points to one of those little hotel bathroom freebies. “It’s nice. I used it this morning.”

“You used this in your tub?” I ask.

“Uh-huh,” she says.

“It’s hair conditioner.”

“I couldn’t

see.

” She cries all over again.

I give her a bath, trying not to wet her hair, which sticks out in crazy greasy clumps. I rub her back with a soapy washcloth. “That’s soooo good,” she moans. Afterward I rub her feet and the lower part of her legs with hotel body lotion.

“See,” she says, “you

are

capable of empathy.”

The doctor employs a nurse to watch his patients at the hotel. She comes in now and tells my sister there’s a car downstairs to take her to the doctor’s office. Still wobbly, my sister readies herself for the ride. In other words, she slips her mules on.

“Don’t worry if anyone sees you in the lobby in your pj’s,” I say. “Really. There’s no way they’d know it was you.”

We close the hotel-room door behind us. The nurse is waiting. She is standing behind a wheelchair. The patient in it looks worse than my sister. This woman looks as if she fell off the Empire State Building, landed on her nose, then got run over by a Hummer. This woman had everything done my sister had done, plus wall-to-wall derm-abrasion. This woman is, quite literally, an open wound.

When we get to the doctor’s office, I blurt: “Why is my sister so asymmetrical?”

“Where?” He takes it personally.

“Her eyes, her jawline.” I’m not happy saying this in front of my sister, but maybe he can still do something. Am I supposed to praise a face that looks like a cake baked in an unreliable oven?

The doctor spins on his heel and storms out of the examining room. In a moment he is back, carrying a Pendaflex. He takes out the “Before” pictures he took of my sister. “Your sister was always asymmetrical,” he points.

“I know most faces are,” I say, looking at my sister’s perfectly symmetrical Befores. Maybe we can’t see asymmetry in faces we grew up with, faces we love. It occurs to me then that the reason symmetry is so pleasing is, it’s the first thing we see. The first thing we see is our mother’s face smiling down at us. Before we even know what seeing is, we know what feeds us and holds us is the same on both sides. On one side there’s an eye. On the other there’s an eye. There are two holes in the nose. And the mouth tilts up on both ends. When babies nurse, when they look at your face, you see their eyes darting, checking this out. Back and forth, back and forth, the symmetry, everything equal. It’s reassuring hence peaceful. It’s balanced. It’s what we know.

I take my sister home and stay three days. I ice her, drive her to the doctor’s, rent movies she can only hear because she still can’t open her eyes. I monitor guests, field calls, talk to her patients, wash her, rub her, and bring her water. I save her from herself when she flaps her arms, throws a fit, and screams she’s going to wash her hair no matter what.

“I’m going to wash my hair! I don’t care! I don’t care!”

“Please.” I hold her arms down. “You’ve been through so much. You can’t blow everything for a shampoo.”

On the second day I ask her, since she can’t chew, if she wants eggs for lunch.

“Yef,” she says. Her speech is muffled because she still can’t move her upper lip. “Make them Mattie’s way.”

“What’s Mattie’s way?”

On her back, her eyes and forehead covered with gauze, blood dripping into the drain, lips too traumatized to move right, my sister gives instructions.

“Let the butter melt on low. Very low. Don’t let it brown or bubble, just melt. Use my small pan with the high straight sides. When the last bit of butter melts, drop four eggs in. Don’t let the yolks break until the whites start to turn opaque. When the whites start to turn, run a fork through the eggs, breaking the yolks. Do that slowly.” My sister uses one finger to make back-and-forth loops like the wire on a potato masher. It is a delicate gesture, something you’d expect to see in

Swan Lake.

“You don’t put any milk in?”

“Milk toughens eggs.”

“No water?”

“No. Nothing. Just butter and eggs. Don’t you remember the way Mattie made them? You could see little pieces of white.”

“Yeah. I do. And the eggs were wet.”

“Wet is very important.”

I re-ice my sister, then go into the kitchen to make the eggs. I think of this face I have loved, the face I grew up with. My sister, the dark-eyed, raven-haired beauty. My beautiful big sister, the one who asked Mademoiselle Dryer, our French teacher, if they French-kissed in France. The great compliment of my childhood was, “Does anybody tell you you look like your sister?”

Maximum swelling comes seventy-two hours after surgery. Tomorrow my sister will look worse. Then she’ll start to look better. But what does better mean? I loved her face before. I don’t want it to look different. If she changes her outside, will her inside change too? I love my sister the way she is. Change is loss. I don’t want to lose anything else in my life, especially my sister’s face.

In the morning I brush my teeth in her guest bathroom and look at myself in the mirror. I’m getting Howdy Doody laugh lines. I don’t have any wrinkles yet, but gravity’s no pal. I’m ready to join the army of men and women who pose for photographs with their fists under their chins to take up the slack. Am I going to do it? I live in a culture where women start talking about plastic surgery in their thirties. Plastic surgery is like going to the dentist. What is my relationship to my face? I like my face. It’s accessible. It’s me people stop and ask, “Which way to Broadway?” or “What floor is lingerie?” People know from my face I won’t hurt them. Occasionally someone says with surprise, “You know, you’re actually kind of beautiful . . . in a way,” as if he’s discovered the tenth planet. What if the surgeon is having a bad day, and he severs a facial nerve, and I spend the rest of my life looking like a stroke victim? I like my face. We’re friends. My face is my partner in crime.

Before I leave Florida, my sister takes eight additional tubs, turns green, opens her eyes a little more, tries to chew chicken curry (the doctor says she’ll heal faster if she has protein), talks about our childhoods and our vastly different interpretations of identical experiences, makes note of who sent flowers, who sent books, who sent food, and who sent nothing, mentions that I really didn’t rub her feet that much, cries a lot, and repeats herself. (It’s the anesthesia.) She doesn’t say a word about the eggs. I did everything she said to do, but I must have cooked them too long. They were so dry they had no shine. Five seconds is all it takes to overcook eggs scrambled Mattie’s way. They’re that delicate. And I couldn’t salt them, because the doctor said salt prolongs the swelling. The eggs I made were a stranger’s eggs. They didn’t taste anything like Mattie’s. If I had to pick something the eggs were like it would be rubber foam.

Dad

BOOST

Take a deep breath, Audrey!” Dad tells Mom. We’re cruising up Palm Beach Lakes Road. Where Sapodilla Avenue meets the draw-bridge, there’s an incline. You go uphill a little. “The highest elevation in Florida,” Dad calls it.

“Fill those lungs, Audrey! We’re going to the mountains!” We pull into the driveway of Good Samaritan Hospital. In June, Dad gets his hip replaced, and his surgeon tells him, “Massive radiation is the new gold standard to prevent scarring.” In July, Dad is diagnosed with myelogenous leukemia. In February it turns acute. Sixty percent of Dad’s blood cells are in “blast.” They’ve stopped working. As we wait for his first experimental chemo to kick in, Dad is kept alive by transfusions three times a week.

I come down twice a month. I know the drill. Dad gets an appointment. Regardless of the appointment, he gets to the office before it opens. Dad can’t wait. He’s wait-intolerant. The staff treats him with affection. Even strangers try to make my father happy. If his appointment is at noon, they take him at eight.

My sister and I give blood to see which one of us is the closest match for bone marrow. We never learn the results. Dr. Harris decides a bone-marrow transplant will kill Dad.

He gets on the scale. Before leukemia Dad weighed 242 pounds. Now he’s 181. Not bad for a big-boned athletic man six feet one and a half. But Dad looks beaky. Mom checks the scale and sucks her breath in. Her line in the sand is drawn at 180, and Dad is now one pound from panic, one pound from being okay to not okay. It’s like that nanosecond in the Holland Tunnel when half your body is in New Jersey, half in New York.

Julie, the tech, tries to find a vein. Dad’s arm is a landscape of magenta hematomas. It’s not her fault. His veins are minuscule. He’s a big man with the veins of a fetus. Specialists are brought in. After rigorous slapping and hot compresses, they strike oil. Then it’s an hour at least to find a blood-donor match and, when the match is found, another hour or two for the fluids and chemo to snake their way in. On a good day it’s a five-hour deal with all the peanut butter crackers you can eat.

“I can’t wait for this new chemo to kick in,” Dad says about an experimental protocol out of M.D. Anderson: Ara-C swirled with Topotecan.

“I can’t wait for this new chemo to kick in,” Dad says about an experimental protocol from Dana Farber called Mylotarg.

“I can’t wait for this new chemo to kick in,” Dad says about Navelbine.

Dad wants to live. He computes how many minutes he has left on earth if he’s lucky. It’s a big number. One year alone is 525,600 minutes. He cautions all of his beloved children and grandchildren not to waste a one.

Because his father died when he was nine, Dad was sure he’d die young too. And because he was sure he would die young, I grew up believing I’d only have him a short time. Every next birthday we met with gratitude. He was living when he thought he was dying and dying when he was sure he would live.

We sit in the examining room. My father listens to the doctor, eager. “Now, Cecil,” Dr. Harris says, “I want you to eat. Have breakfast three times a day if that’s the food you can get down. You need twelve hundred calories a day at least. Drink Boost. You can’t get better if you don’t eat.”

Dad loathes Boost, an artificially flavored dietary supplement. But an eight-ounce can of Boost Plus has 360 calories. He and my mother negotiate every sip.

“Just three more!” Mom says.

“Audrey, I can’t.”

“Just two. Just two and you’re done!”

“I hate this crap.”

“If you drain the glass, Cecil, I won’t bother you the rest of the day. That’s a promise.”

Every long drag is her victory. Every turning away, her defeat. I make a DAD’S DAILY CALORIC INTAKE chart on his computer. I print out thirty and attach them to a clipboard. At night we total the calories.

“An egg is seventy-five.”

“Yes, but I put butter on it.”

“Is pudding the same as tapioca? What if you made the pudding with heavy cream?”

Dr. Harris is firm about the eating. Dad hangs his head. He can’t chew. He can barely swallow what slides down. The chemo has done something vicious to the inside of his mouth. The nerves of his teeth are exposed. Eating and drinking are agony. One day, lying next to him in bed, I watch Dad’s lips slip off. They turn white, quiver, and slough in clumps like wet Kleenex. Raw flesh is underneath.

At some point during this visit I tell Dad what I want to make sure I tell him: “I love you Dad. I love you without reservation. You have been the best father in the world to me. Thank you. Thank you for teaching me

Falco peregrinus

is the fastest animal on earth. Thank you for showing me everything has magic. Thank you for giving me your spurs from Colorado. Thank you for your sprawling embrace of the world. Thank you for showing me it’s okay to break the rules. Thank you for everything you’ve taught me. I am widely envied for having you as my father. Always have been.

I

envy me. There is not a day that goes by I’m not grateful. I love you, love you, love you.” I cover his face with kisses. “I love you so very much, Dad.” By now I’m crying.

“Uh-oh,” he says. “Here comes Niagara Falls. Here comes the waterworks.”

“I (sob, sob) love (boohoo) ya, Daddy (waaaaaaaaa).”

“Cut the crap,” he says.

We are on the cancer roller-coaster, the

cancer

coaster, the yea-boo yea-boo ride of a lifetime. Dad is bald now. Six months ago, before the hip surgery, he was playing tennis every day, tooling around Boca in his black leather jacket on his 1973 mint-condition BMW 750 CSR. Now he’s tooling around in a wheelchair. He sleeps in the downstairs guest bedroom, and around five every morning I hear the determined tap-tap

-kuh

lap of the walker as he makes his way into his real bedroom to lie next to my mother. It’s a long, hard journey between bedrooms. When I walk in at eight, there they are— Mom asleep on her back, Dad on his side, curled into her the way they slept when I was a kid.

When I get home, I go to

wordsmith.org

and check anagrams for CECIL VOLK. Eight matches come up, the first being CLICK LOVE. How apt for my loving father who taught me how to use the computer. I check PATRICIA VOLK. I get sixteen pages, the most interesting are: IRK LATVIA COP, PRICK TO AVAIL, VITA LIP CROAK, and the stunning pronouncement CRAP VIA LIT OK.

Dad’s determined to get better. He will get better. He knows this. He is a competitor. It’s one more opponent, cancer of the blood.

Everybody has food ideas.

“Liverwurst. You don’t have to chew it.”

“Steak blood.”

“Jell-O made with fruit syrup.”

“Really soggy French toast with a lot of maple syrup.”

“A chocolate malted is the single most fattening thing on earth.”

We have to stoke him with calories.

Ice cream is one of Dad’s favorite foods. He can work through a pint or two watching TV after dinner. In Publix, the local supermarket, we compare calorie counts. We want the ice cream with the highest. Edy’s Chocolate Fudge Mousse is only 160 a serving. Turkey Hill Chocolate Peanut Butter Cup, 180. Friendly’s Reese’s Pieces comes in at 230. Who knew ice cream was so dietetic? I reach for the Haagen-Dazs Chocolate, 270! Now we’re getting somewhere. Ben & Jerry’s Peanut Butter Cup wins at 380. Mom has gone from “Cecil, stop putting that in your mouth!” to “Cecil, please put that in your mouth!” with no intermission.

“I don’t want anyone to mention food around me,” Dad announces. “Please.”

We try to stop, but how can he rally if he doesn’t eat?

My sister goes into the guest bedroom, where Dad and his full-time nurse, Donna Claire, sleep. It’s the room I usually stay in, a room that says End of the Millennium in Boca Raton, Florida. It has eighteen-foot ceilings and eleven walls and a porthole in the giant closet for viewing palms as you dress.

Donna Claire takes flawless care of Dad. He teases her. “She beats me with a rubber hose so the marks won’t show,” he says. “She does it when no one’s looking. On the bottom of my feet.” Donna cracks up. “She’s vicious. A

killer.

”

My sister goes into the room. She’s there a long time. I peek in. She’s on the bed, facing Dad.

Later I ask. “What were you doing in there?”

“Visualization,” she says. “Meditation technique. Hypnosis.”

“Did he respond?”

“He cried.”

“Oh, no!” I burst into tears. I’ve never seen my father cry.

We heat the water to ninety degrees. Dad feels good in the pool. It’s the place where, weightless, he’s most like he used to be. But he’s caught in a trap. The more he exercises, the more oxygenated blood he uses up. Dad needs to exercise. It’s what makes him feel good. But in the end, it will make him feel worse. On a good day, because you can’t count on anything for more than a day, Dad will go in the pool twice. He’ll float on his back with his arms looped under a long Styrofoam pool noodle. I noodle alongside him and make up a song:

When I swim in the pool with my Dad

There is nothing that makes me so glad

We’ll swim and we’ll play

Throughout the whole day

Then Dad supplies the last line:

Now what about that could be bad?

Or

With nothing to make us feel sad.

Or

Until your dear mother gets mad.

We’ll laugh until Mom uses her “You bad boy!” voice and tells him it’s time to come out.

“Now?” Dad says. He’s having fun. But Mom knows. He’s using up good blood drifting around.

Dad pulls himself up the pool steps and collapses in his waterproof wheelchair. His chin falls on his chest. Donna showers and soaps him with warm water from a sprayer. Tenderly, she dabs 45 SPF sunblock cream on his newly hairless head.

When Dad embarks on a new chemo, when all his white blood cells or red cells or blast cells or whatever Dr. Harris is trying to kill at the moment get killed, at Dad’s lowest point, we wear masks and gowns, wash our hands with bactericide, take our street shoes off, and don’t let our skin come in contact with his. His immunity is zero. He has no resistance. But if I suck my breath in, the mask conforms to my lips and I can kiss him through the mask and it feels like a kiss. Dad loves kisses. He loves to be touched.

After a particularly brutal chemo, Dad says he will be happy again when he can watch TV and read the newspaper. He needs strength to watch TV. He needs strength to open his eyes. Mom and I test-drive some La-Z-Boy chairs so Dad can sit comfortably in front of the TV when he’s up to it.

The La-Z-Boy becomes command central. Freddie, the gardener whose daughter Dad’s helping through school, drifts in and discusses trimming the banana trees and new plants for the front.

“Pull out all the stops, Freddie,” Dad says. “I want it gorgeous for Audrey.”

The Boca Boys—Dad’s Tuesday buddy group—trickle in. When Dad moved to Boca, he found three comrades right away. Dad, Aaron, Milton, and Arnold called themselves Bunk 4. They were going to have fun together, like in camp. Dad welded them iridescent BUNK 4 license plates for their cars. Every Tuesday they’d meet and vote on where to go for the cheapest lunch. Then they’d see a Jean-Claude Van Damme or Jackie Chan movie their wives would never sit through.

Word gets out. Bunk 4 touches a nerve. The group swells to seventeen and meets every Tuesday in Dad’s kitchen. They change their name from Bunk 4 to the Boca Boys. On odd-numbered Tuesdays they wear black tennis shirts with the BOCA BOYS logo embroidered over their hearts. On even Tuesdays, red. They have matching baseball caps with the logo too. And engraved Swiss army knives. The Boca Boys get written up in the

Florida Sun-Sentinel:

“Volk calls the meeting of the group to order with several clangs of a brass bell he welded himself. He admits it’s not an easy bunch to pull together. ‘We got half a dozen conversations going on here at once,’ said Volk, clanging the bell and calling for order a second time. ‘Okay, what movie are we going to see? How about

No Escape

with Ray Liotta?’ ”

After the Boca Boys vote on the movie, they fan their discount lunch coupons all over Dad’s kitchen table. Every week they pick the biggest, cheapest meal you can get for under four dollars. That’s a founding Boca Boys principle. After the vote they thunder out in packed cars and seventeen laughing white-haired men storm an IHOP or a Bagelworks or a deli that has soup and a sandwich and a bottomless soft drink for $3.49. If nothing in the paper appeals, there is always the foot-long hot dog for a dollar at Costco. The consensus is the foot-long Costco dollar dog may be the bargain of the century. Whenever Dad picks me up at the airport, as soon as we hit Powerline Road, his eyes light, he leans over and says, “Wanna foot-long hot dog at Costco?” The Boca Boys eat lunch early. They want to make the empty noon show at the movies so every boy gets an aisle seat.

Dad’s used to being in control. He keeps hoping. We all do. My sister gives him Meditapes, powerful visualization tapes she narrates for people going into surgery, insomniacs, people who have stress or are getting chemo. I bring Dad a boom box with George Shearing and Tito Puente CDs. My friend Kathy finds a recipe on the Internet for capsaicin candy, a hot-pepper candy that will relieve Dad’s mouth. My sister consults her rabbi and a psychic: “Do you think he can get better?” Both agree he can. We go to her

shul

and pray. We get the whole

shul

to pray. We call all our doctor friends. Norm Gottlieb sends reprints from medical magazines. Michael Motro puts us in touch with the chemo pioneers in Israel and suggests we find out why Dad got this particular leukemia in the first place. Dad doesn’t care, but I’d like to know. Next door to the store there was a dry cleaner, and the paper says exposure to dry-cleaning fumes can cause cancer. In the Twenty-eighth Street studio Dad shared with Zero Mostel, who was a serious painter and a passionate lover of Morgen’s center-cut tongue sandwiches, Dad worked with chemicals. Maybe it was the patinas Dad used finishing sculptures in his studio at home. Maybe it was the hip radiation. Maybe he’s living in the Love Canal of Florida. Even though there’s a water filter under the kitchen sink, does it filter out everything? Thirty-eight states have poisoned water tables. A twelve-ounce bottle of Evian costs $1.25. A twelve-ounce Coke is 80 cents. Why does water cost more than Coke? Soon water will cost more than wine. They’ll date the bottles so when you sip the water, you can say, “Ah, 1994 Crystal Geyser. A good year. That was before the nuclear waste dump polluted the Eastern Sierra.” Seventy-three percent of all cancers are environmental. I don’t trust the water my parents drink. Not a bit.