Stuffed (22 page)

We are going to scatter Dad in the Atlantic. We board our friend Jim’s boat. Mom sits portside embracing the box. She’s huddled over it. No one speaks. Jim puts Mozart on the CD player. The sun is setting. We’ve told Mom what Dad asked us to do. We’ve told her he designed heart lockets for us to put a bit of his ashes in. Lockets we can wear and always have him with us. But Mom wants all of him together. When we get to 25°38.552N by 80°11.863W, when we no longer see land, at that precise point we take turns scattering Dad from a deck off the stern while the sun goes down. My nephew Michael grips the back of our shirts so we don’t fall overboard. The ashes are not like I’ve read about. They’re not brown or greasy. They are cement gray with shards of white and black in them. When it’s my turn, I watch them cloud out in the water, and when I raise the plastic bag, the ashes in the neck of it are so heavy they don’t go back in the bag. They spill all over my feet. I try to scoop them up. “I’m sorry I’m sorry I’m sorry I’m sorry I’m sorry,” I keep saying while Michael hoses them off. I lose track of time. Someone pulls me back to my seat. Mom goes last. She seems so fragile, so newly small.

My sister and I look at each other. I lick my hand. She licks hers. The sun is down. We head back. We dock and go out to a place Dad liked for dinner. A few days later, before I leave for New York, Mom and I head for our favorite beach at Red Reef. We plow through the waves, and I think about the summer the four of us vacationed on the Lido. Dad loved the Adriatic. It was warm and clear. He loved the little crabs in the shallow water. “Granchi,” he called them, and teased my mother. “You’re a

vecchio

granchi,” he’d say, and laugh.

Mom and I bob in the ocean. It’s like the butterfly flapping its wings in Japan. Over time the breeze wafts all over the world. Anything you put in water anywhere eventually makes its way into every drop of water on the planet. We’re swimming with Dad. Mom and I talk and drift. We have a good time.

Back in New York, it’s my sister on the phone.

“I miss him,” I say.

She gasps, then goes silent. Finally she says, “I can’t believe you’re saying that. That’s so the

least

of it.”

Does my sister think my grief is less than profound?

I put on my running shoes and go to the park. I look for a bench for Dad. Every bench in Central Park has a number on the back, and if it’s still available, you can buy it and have a personalized plaque screwed on the front. I walk by the tennis courts. Dad loved tennis. He loved to play it and to watch it. But these benches aren’t in great shape and they’re right up against a chain-link fence. I find a brand-new bench I like beautifully shaded near a fountain, but when I call the Central Park Conservancy, I learn all the benches in that area are reserved for Helen Frankenthaler, who has given the park $100,000. I set out again. I want a bench on my beaten path, a bench I can sit on every day, a bench with meaning.

I narrow the benches down to two. One is by the south gatehouse, but the view is partially obstructed. I decide to go with the bench next to Madeline Kahn’s, where the bridle path meets the reservoir track and the drive just north of the West Side entrance to the Eighty-sixth Street transverse. People pour into the park here. The views are west, where we lived, east, where I live now, and the bench faces downtown, where Dad worked. The bridle path is where Mom and Dad used to ride on weekends, and I can sit on this bench every morning when I walk around the reservoir. Two London plane trees frame the view.

Mom dictates the plaque:

IN LOVING MEMORY OF

CECILS. VOLK

AUDREY PATRICIA JO ANN

There are little hearts between our names.

When Mom comes up for Thanksgiving, I take her to see the bench. The one to Dad’s left has been sold. That plaque honors the Starrett family, the people who built the Municipal Building on the land Jacob Volk cleared.

Mom sits on Dad’s bench. We chat. She tells me that after she broke her back on the bridle path, after it healed, Dad took her to a dude ranch to practice getting thrown. “We’d go every weekend,” Mom says. “I had to keep falling off so I’d learn the right way to fall off and never break my back again.”

I tell her when I think of Dad going to the hospital for transfusions, I’m not sad. “People were always so happy to see him,” I say.

“He enjoyed getting everyone under his spell,” my mother says. “He interacted to the end.”

A runner comes by and we ask her to take our picture with our arms curled above the plaque. As we get up to go, Mom studies Dad’s bench in relation to his neighbors’. She takes the three benches in and says, “Why did they have to put dates on Madeline Kahn’s? And the Starrett family! Look at all those words. It’s overwritten. Our bench is the best.”

Grief is a surprise. It’s not a long wailing process that gradually tapers off. The intensity of it comes and goes. Remembering good things is purely joyful. There’s

laughter

. I don’t feel loss all the time, because my father is vivid and in so much I do. How I dice. How I make knots. Clipping my toenails his prescribed way. (You never know how strange your family is until you see the expression on someone’s face when you say, “My father always cuts my toenails. He doesn’t trust other people.”) When something breaks, Dad’s on my shoulder, saying, “Study how it works!” or “Get out the manuals!” (stored in a labeled MANUALS file). I look up words in the dictionary, finding winsome new ones on the way. Since he cared deeply about the edge on knives, since every time he came to visit, the first thing he’d do was walk into my kitchen and check my knives against the pillow of his thumb, I get them professionally sharpened and check them against my thumb. When I look in the mirror, he’s there smiling back. Much of the time it feels as if Dad’s with me. “My heart with pleasure fills.” I fall apart only when I think of him perplexed and suffering. Thinking of that whacks me like a bat behind the knees.

“When someone dies, you don’t cry for them,” Professor Fred Haaucke told our aesthetics class. “They’re dead. You cry for

you.

” I’d hoped this was true. It’s not. I don’t cry for me because I miss him. I cry for how Dad suffered.

When I was growing up, I had three hobbies. I collected stamps, tropical fish, and bugs. All three are microcosms. Stamps are miniature portraits, landscapes, and historical reenactments.

Washington Crossing the

Delaware

an inch big is a defining moment in history smaller than your toe. A tropical fish aquarium is a universe complete with birth and death and evolution, all right on top of your dresser. And bugs, how they move and behave, how they interact, what they do to survive, and how they plod on no matter what, are microscopic role models. Microcosms fascinate because they tell big stories on an accessible scale. They are worlds you can hold in your hand. Now I collect snow globes, three-inch cities in perpetual blizzards. But my most interesting microcosm is the one I was born with, family. Family is what we first know of the world. Family

is

the world, your very own living microcosm of humanity, with its heroes and victims and martyrs and failures, beauties and gamblers, hawks and lovers, cowards and fakes, dreamers and steam-rollers, and the people who quietly get the job done. Every behavior in the world is there to watch at the dinner table. You study them. You learn. You see how they change and how they stay the same. But if you think you can really know them, you’re missing the point. The point isn’t how well you know somebody. The point is this: In a family you don’t come from nowhere. You enter the world already part of something. The myths and behaviors are all there to model yourself on or against. You are who you came from. There is no escape, but there is transmutation. Family is how you become who you will be. It’s through family you learn there are no limits on ideas, nothing is strange if it seems right, and if you believe in what you do, who cares what anybody else thinks. Knowing so much about them, how open-hearted can you bear to be? You were born with the chance to love them. You might as well. They’re yours.

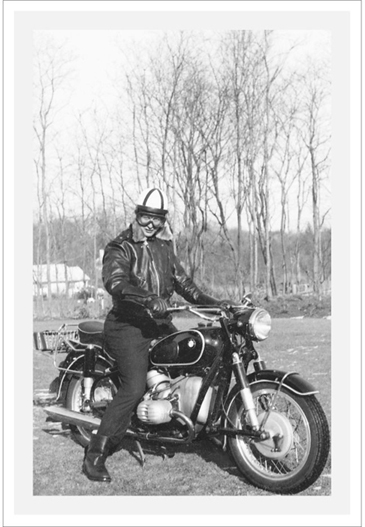

Cecil Sussman Volk in full regalia

STEAMERS

Dad raises his chin and buckles his helmet. He zips his black leather jacket, the one with the new gusset in the back. He pulls on the black leather gloves with the flared cuffs and flexes his fingers. He swings his leg over the bike, forwards his weight to lift the kick-stand, then revs.

Vroom, VROOM.

VROOOOOOOM.

He adjusts the gas. The bike is roaring. He flips his face mask down and nods for me to hop on. It’s Sunday. He can’t find some papers. We’re going to the store for the last time.

The Long Island Expressway is wide-open. We sail into the city, past Lefrak “If You Lived Here, You’d Be Home by Now” City, past the expanding and contracting propane tank and the cemetery where Dad likes to note, “People are dying to get in there,” until the skyline rises, surprising yet familiar every time.

Dad parks the bike in front of the store, and we go in through the side entrance. It’s dark and quiet. We head upstairs through the secret door. The walls of Morgen’s are booked mahogany to the ceiling, where they meet a dentil molding. Set in one page of the mahogany is a knobless interior-hinged door you wouldn’t know was there unless you knew it was there. Behind the secret door, to the right, are a desk and a phone where Dad negotiates orders for the day, books parties, takes reservations. To the left a narrow staircase twists up to a room that has a twenty-foot desk and a six-foot safe at the far end. Like the downstairs desk, it’s covered with piles of paper, drifts and stacks, papers on spindles. Bad checks are taped to the wall.

Morgana meows. The stray cat Dad rescued lives in the office. Dad once wanted to be a veterinarian. Dogs and cats sense his goodwill. In a roomful of people he’s the first to get nuzzled. Morgana is fat and glossy. Dad’s brought her back to life. She tucks through his ankles.

There’s a quarter-inch hole in the east wall of the office. You can peep through it and check out the floor. The accountants and the biller work up here. It’s where cash is kept and where Dad hides his Smith & Wesson .38 Chiefs Special Revolver Model No. 36 and his Hi-Standard .22 Long Rifle with Supermatic Citation that he uses for target practice. He carries the .38 when he goes to the bank. With the advent of plastic, there’s not that much money. But there’s still enough and you don’t have to be a genius to know that when Cecil Volk of Morgen’s is speed-walking down Broadway, he’s got cash.

Dad sifts through some papers. I remember the Sunday I rode in with him after the police called to say the store had been robbed. It was the only time I saw the safe open with its smaller safe inside. I remember lunches up here because the store was so packed, they couldn’t spare a table. I’d eat my club sandwich at the desk, playing with the adding machine and the magnetized paper-clip holder.

Dad can’t find what he’s looking for. He strokes Morgana and turns out the light. We walk through the silent restaurant, a graveyard of red leather chairs upended on tables. Dad threads his way easily to the other staircase near the hatcheck booth, where the concessionaire sold fat cigars, Sen-Sen, and the strangest-tasting mint in the world—C. Howard’s Violet, lilac squares wrapped in purple foil that tasted like flowers.

The wide terrazzo stairs lead to the subterranean Morgen’s. It’s bigger than the main floor and reserved for private bookings. It was here I had my sixth-grade birthday party. Three tables were set in a U, as if it were a testimonial dinner. On top of white table-cloths, forming a green U inside the linen U, Dad laid a spine of ferns. My class had burgers. Later we walked to Times Square, and I got my first kiss. Richie Mishkin slung his arm around my neck and pulled my head toward his. We documented the moment in a photo booth for proof.

Downstairs, Dad leads me to a place I’ve never seen, a lowceilinged storage area. While he looks for the missing papers, he says to me, “Take anything you want.”

The store has been sold. Not the store exactly, but the lease to the store, a lease Dad worked two tough years negotiating. An Italian restaurant is moving in. In four years it will be in the newspapers. A woman in a red Mercedes will drive through the plate-glass window at 141 West Thirty-eighth Street and kill a customer at table 3, the small booth to the left of the entrance where Mom and Dad used to have coffee before the lunch crush. The Italian restaurant is subletting the store from Dad. It was a good move negotiating that lease. It’s income. When Uncle Bob closed Morgen’s East, that was it, his lease was up.

Dad’s bike has two saddlebags. I can’t take too much. I look for things that will last, so my home will never be without stuff from the store. I look for infinite shelf life, a lifetime supply of something. I take one-pound containers of dry mustard, paprika, and cinnamon. I take two thousand lamb-chop panties, one bag gold, one white. I take a box of one thousand Morgen’s cellophanefrilled toothpicks and a box of five hundred Stir-eo Straws my kids will love, a box of one hundred silver petit-four moules and two gallons of nonpareils, tiny beads of colored sugar the kids eat on yogurt, on

anything.

When I want Polly and Peter to eat their vegetables, I sprinkle them with Morgen’s nonpareils. I take a mason jar of Morgen’s seasoning salt.

“May I have something from the kitchen, Dad?”

He’s already set me up with knives. I take the enormous wooden salad bowl my favorite Morgen’s chopped chef salad was chopped in. This bowl will take up a whole saddlebag, but I love it. It has a honey patina and more crosshatches than a Dürer. I am sure this bowl, like Mom’s chopped-egg bowl, imparts flavor. I take two restaurant-grade saucepans, the sloping dull metal kind with thick pitted stay-cool handles riveted to the sides. From behind the bar I take a round cocktail strainer and a long spoon the bartender uses to swizzle drinks. It has a red plastic ball on top, and the shaft is turned like a drill bit. I don’t make mixed drinks, but I’ve only seen a spoon like this at Morgen’s. I pack up two cartons of Morgen’s matches and a few menus.

I don’t like lasts. Even if I am moving to an apartment with more room, a bigger and better apartment, I’m sad leaving the old place. “This is the last time I will cook oatmeal on this stove.” “This is the last time I will use this tub.” “This is the last time I’ll come home from this particular job with my children racing to this particular door.” “This is the last time I’ll wake up with the sun hitting my face this particular way.” It doesn’t matter if what I’m headed for is better. It’s about a thing disappearing. Something will never be again.

So the last Morgen’s is closing. When Dad locks the doors for the last time, the hundred-year story of our New York restaurant family is

fini

. From Sussman Volk in 1888 to Cecil Sussman Volk in 1988. One complete century. This last store was the hub of the garment center in the hub of the city in the hub of the nation that’s the hub of the planet. Mom and Dad fed the people that clothed the country when MADE IN AMERICA was the label of choice. It was a place that gave good value. A place where people knew that a family was there and they’d knock themselves out to take care of you. Whether they were working during the day or having a bite before the theater, customers could count on a sprawling menu filled with freshly prepared first-rate imaginative food. For one hundred years our family fed New York. In my fraction of that time I’ve lost lots of restaurants: Schrafft’s, the Automat, the counter at Henry Halper’s, Mary Elizabeth’s, Le Pavillon, Charda’s, the vegetable plate at the New York Women’s Exchange. I’ve lost stores too, the three B’s: Best’s, Bonwit’s, and B. Altman’s. And customs: wearing gloves to walk down Fifth Avenue,

wanting

to walk down Fifth Avenue,

bon voyage

parties, crinolines, children playing potsy on the sidewalk, jump seats in cabs. We listened to the

Victrola.

We packed our clothes in a

valise.

And even though it ran on electricity, we stored our food in the

icebox.

Photos of my grandfathers are starting to look young. Even Bing Crosby’s starting to look young. One generation ago, four generations met weekly for dinner. Now those people live in Honolulu, Scottsdale, and Boca Raton.

The restaurant business, feeding people, will always be a way to make a living. To make extra money in college both my children get their bartending licenses. While continuing his studies, Peter mans the bar at The Conservatory in the Mayflower Hotel on Central Park West. At night he waits tables at Farfalle on Columbus Avenue. Polly, my daughter, gets a job hostessing at Restaurant Daniel. When she seats people (like her Great-great-grandpa Louis, her Great-grandma Polly, and my mother), they eagerly press fifty- or hundred-dollar bills in her hand. Before dinner starts Polly answers the phone. “Zees eez Dahn-yell-uh,” Bruno has told her to say. “Ow may I elp you?”

But just when I think our family is out of the food business, my sister’s husband opens a New York–style food store called JoAnna’s Marketplace in Coral Gables. In JoAnna’s first year of business Alan wins the

Miami Herald

’s first prize for his Chocolate Decadence Cake with a ganache so rich yet light it seems like a new category of food. His sons, Michael and John, go into JoAnna’s with him. They marry, and Kelly and Tonya go in too. Like the tables our family sets, JoAnna’s Marketplace has room for everybody. Now Alan and the boys have opened another JoAnna’s in the Grove. On Thanksgiving, JoAnna’s bastes four hundred turkeys and opens its doors at five a.m. A restaurant closes. A food store opens. We’re still feeding people.

Patricia Gay?” Dad calls in the dark. He’s found the papers. We ride home on the bike. On the way he turns his head sideways and yells, “Want some lunch?”

“Sure,” I yell back.

He passes the turnoff for Kings Point and heads for Port Washington. Last time in store, last Louie’s for clams. We order two large bowls of steamers. We pull them out of the shells by their muscular black siphons, swish them free of sand in briny broth, then dip them in a bowl of clarified butter. We bite their rubbery necks off.

“You realize you’re eating a whole animal,” Dad says.

“Stomach, heart, mouth, foot, esophagus, gills, mantle, digestive system, and everything that implies, Dad.”

“Well, at least they’re dead. When you eat raw clams and oysters, they’re still alive.”

We toss the empty shells in the big bowl between us. I look out on the town dock, a favorite make-out place where grinning police liked to tap the fogged-up windows and say, “Does your mother know you’re here?”

Careful not to disturb silt that’s settled on the bottom, we sip the gray broth. “Did you know, there are over twelve thousand species of clams?”

“No, Dad.”

“Mollusks are bivalves,” he continues. “

Bivalvia.

See this horny ligament? It works like a hinge to let the shells open. And these?” He points to thready nuggets still stuck on the dorsal interior of the shells. “These are the adductor muscles. They’re too small to eat in a steamer, but scallops are adductor muscles. We’re eating soft-shell clams,

Mya arenaria.

Do you know how they reproduce, Petroushka?”

“Tell me.”

“The female releases eggs into the water. The male releases sperm. Somehow they find each other.”

“I’m glad I’m not a clam, Dad.”

“Me too.”

As we wipe the butter off our chins, Dad says, “Did I ever tell you sailors chew clamshells for calcium?”

We head for home. Dad’s a careful but aggressive motorcyclist. He believes in driving offensively. We swerve in and out of traffic, not for the thrill but because the car in front of us is being driven with less than optimum skill. It’s too slow, too erratic (the geezer phenomenon), fails to observe a signal. It’s a late braker, an early braker, a stuttering braker, a bobber and weaver, any one of the countless things the motorist in front of a biker can do wrong.

The wind whips down the neck of my jacket. The sun warms my face. It’s a gorgeous day. What clouds there are look like gauze. I have two choices on the bike: I can hold on to the strap that bisects the seat. Or I can put my arms around my father’s waist. I opt for his waist. We lean left. We lean right. We get so close to other cars I see eyebrows rise. Horns honk. Drivers shout. Somebody shoots us the bird. Cars peel out of our path, the road opens wide. We lean so low into a curve I see flecks of mica in the blacktop. And I feel the way I always feel with my father, safe.