Supercontinent: Ten Billion Years in the Life of Our Planet (8 page)

Read Supercontinent: Ten Billion Years in the Life of Our Planet Online

Authors: Ted Nield

Suess was a great coiner of words. Geologists use them all the time without realizing it. Words like

sima

,

Tethys, Panthalassa, epeirogenesis, syntaxis and eustasy,

unfamiliar to most people, have sewn Suess into the fabric of geological language. Yet even everyday speech bears him testimony. Every time we talk of ‘the biosphere’, meaning the sum total of all living things on Earth, we invoke Eduard Suess. None of his many terms, however, has caused as much etymological controversy as ‘Gondwanaland’.

Suess chose the ancient name meaning ‘Kingdom of the Gonds’. The Gonds, like the Tamils, were Dravidian peoples, and once inhabited much of what is now Madhya Pradesh, in the heart of peninsular India. Their kingdom’s name, Gondwana, had already been attached by palaeontologists to the typical fossil plants that seemed to link the now far-flung southern continents, in the term ‘Gondwana

Assemblage’. For Suess ‘Gondwanaland’ meant the land whose rocks yielded this assemblage.

By the time Suess came to write his last volume, his lost

supercontinent

had grown to include: ‘South America from the Andes to the east coast between the Orinoco and Cape Corrientes, the Falkland islands, Africa and the southern offshoots of the Great Atlas to the Cape mountains, also Syria, Arabia, Madagascar, the Indian

peninsula

, and Ceylon.’ Its characteristic fossil plants had now been found in the Permian rocks of South America, South Africa, India and Australia. Once the specimens salvaged from Scott’s last tent had made it back to London, Gondwanaland would extend its dominion even further, and include the great frozen continent of Antarctica. This last fact never made it into Suess’s book, as it was first revealed in print five years after the last volume of

Das Antlitz

came out, in the same year that Suess died.

Though an obvious point, the main thing to remember about supercontinents is that they have vanished – for the moment. As Suess was the first to find, bringing a lost supercontinent back to life was as nothing to the problem of accounting for its disappearance. Just where did Gondwanaland go? ‘Gondwanaland was a continuous

continent

. Then it broke down, sometimes along extensive rectilinear fractures, into fragments,’ Suess wrote. A modern reader,

encountering

this with a head full of continental drift, might conclude that Suess was not only father of the supercontinent but of continental drift as well. But this would be wrong. In Suess’s worldview the Earth was shrinking inexorably as it cooled; his lost continents had sunk, like those lands of myth Atlantis, Lemuria and Mu, beneath the sea.

5

Sit down before fact as a little child, be prepared to give up every conceived notion … or you will learn nothing.

THOMAS HENRY HUXLEY

For all the eternity of the ocean, there is nothing timeless about its shoreline. Over great spans of geological time the ocean may invade large tracts of the continents and create vast, shallow seas, as it did when chalk, for example, came to be deposited over so much of the Earth. Also, ice ages pull water out of the oceans and pile it up on land, causing the global sea level to fall hundreds of metres and

leaving

the continental shelves (those fringes of continent temporarily covered by the sea) fully exposed.

The crust of the Earth itself also goes up and down. When I was a research student, working on the Baltic island of Gotland, I had the good fortune to know a local architect named Arne Philip who had a passion for geology. He would criss-cross the island in his MG

convertible

, theodolite in the back seat, making surveys of thousands of the ancient beach ridges that ring the island and all its outlying islets, recording the high-water marks achieved in the Baltic region

thousands

of years ago. Arne collected shelves full of data on these ‘storm beaches’ and plotted the results on gigantic maps. I do not think,

however

, that he ever reached any firm conclusions.

The reason is this: when ice ages end, and the heavy ice is removed after tens of thousands of years, the land recovers, just as a cushion does when you get up. The Earth, on its vast timescale at least, is soft to the touch, and this recovery has been happening in the Baltic for 10,000 years. But Arne’s problem was that his equation had (at least) two variables. At the end of the Ice Age the sea level rose globally; but locally the land was also rising where it had been covered by thick ice sheets. Gotland’s storm-beach heights were therefore a function of two unknown variables – and almost impossible to disentangle.

At least Arne knew what he was dealing with, and understood that the Baltic region is rising and why. Suess did not enjoy the benefit of such well-established explanations. In his day the relative ups and downs of crust and sea over geological time were hotly contested issues, attempted explanations for which came to occupy much of his gigantic book. This plastic quality, this mobility of the rocky crust (the very fact that, given time and sustained pressure, rocks

flow

), eventually proved crucial to moving beyond Suess’s contraction theory as an explanation for the break-up of Gondwanaland, and towards building a truly accurate map of the supercontinent he

discovered

. Yet although geologists now regard as obvious this plastic behaviour of rock over long periods, most non-geologists are still quite surprised to hear how fickle the relationship between the land and sea can be: and not just in Scandinavia.

One day in late 2002 a mysterious volcanic island reappeared in the middle of a busy shipping lane off Sicily. A diplomatic row quickly flared over whose territory this resurgent island would be. Did

previous

claims still hold? Opinion was hot, strong and diverse. And

caught in the middle of it were geologists: the one group that knew most, and cared least for territorial squabbles.

This speck of strategically important potential land has become known to the British as the Graham Bank volcano (and to the Italians as Isola Ferdinandea, the French as L’Isle Julia, and to

various

others as Nerita, Hotham, Corrao and Sciacca). Professor Antonio Zichichi, a geophysicist at the Ettore Majorano Centre in Sicily, put it simply, and perhaps with a little exasperation, when he told the Belgian newspaper

Le Soir

: ‘It goes up and down because the Earth’s crust goes up and down and that’s that!’ But geologists were not always so apparently uninterested in the question of the Earth’s crust’s ups and downs.

It was Enzo Boschi of Italy’s Institute of Geophysics and

Volcanology

who seems to have rekindled this century’s new-found interest in the Graham Bank, in an interview with Reuters, following reports of water disturbance in the area. Dr Boschi had said the volcano might erupt ‘in a few weeks or months’. This quote quickly spread through the online media and resulted in a thoughtful feature by Rose George in the UK newspaper the

Independent

. Then the whole thing went quiet for a month, until the Italian Naval League

reawakened

the story by demanding that Italy do something to prevent perfidious Albion (or any other foreign nation) from stealing their island again.

The thing about volcanoes is that they erupt from time to time, and as Professor Zichichi knew well, when they do this they tend to swell up as the magma rises (and subsequently down after it erupts). The new activity of 2003 was just the latest phase in the life of the Graham Bank volcano. The previous time it had appeared above the water was in 1831. In the very year that Eduard Suess was born, a small Mediterranean island a few hundred metres across was also coming into the world, just off Italy’s toe.

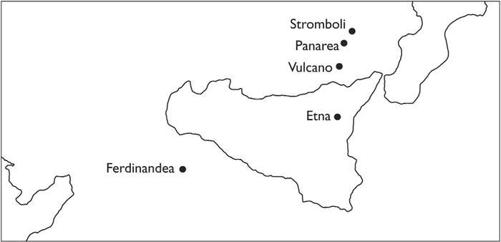

Location of Ferdinandea, or Graham Bank as the British have it.

The British name derives from Admiral Sir James Robert George Graham, First Lord of the Admiralty, who claimed the newly emerged island for Britain by planting a flag on it. This did not stop competing colonial claims by France, Spain and of course the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The Italians, whose nation now encompasses the Two Sicilies, still refer to Graham Bank as Ferdinandea, after King Ferdinand II, who ruled the Two Sicilies from 1830 to 1859. The competing colonial nations only gave up their territorial squabble when they realized that the sea had eroded the island away completely while their backs were turned.

Graham Bank sometimes seems to have been put on Earth simply to make fools out of men. As recently as 1987 US warplanes spotted it, believed it to be a Libyan submarine and dropped depths charges on it. Even more recently the two surviving relatives of Ferdinand II commissioned a plaque to be affixed to the then still submerged

volcanic

reef, claiming it for Italy should it ever rise again. Astute readers will not miss the logical difficulty inherent in the concept of a ‘

submerged

island’. For is not a ‘submerged island’ just another bit of the

seabed? But neither national sentiment nor

fin de race

royals find much use for logic.

The prime mover in the affair with the plaque was one Domenico Macaluso, surgeon, voluntary ‘Inspector of Sicilian Cultural Riches’ and, as luck would have it, a keen diver. He first became interested in Ferdinandea in February 2000, when news of fresh eruptions first broke. These reports were all couched in terms of the reappearance of a ‘lost corner of the British Empire’, thus ruffling some Italian plumage. The well-connected Macalusa successfully persuaded Charles and Camilla de Bourbon to commission a 150kg marble tablet, which he and some friends duly installed, twenty metres under the waves, in March 2002. (Mysteriously, it was later smashed into twelve pieces by a person or persons unknown.)

That year Filippo D’Arpa, a journalist on a Sicilian newspaper, published a timely novel about the events of 1831:

L’isola che se ne andò

(

The island that went away

). He summed up the fiasco well when he told the

Independent

: ‘[Ferdinandea] is a metaphor on the

ridiculousness

of power. This rock is worth nothing, it’s no use as a territorial possession, and yet the French and the Bourbons … nearly came to war [and] 160 years later, England and Italy are still fighting.’

If only politicians would listen to geologists, perhaps they would learn to curb their enthusiasm. For alongside this grand

opera

buffa

, the geology of Graham Bank is really rather boring. Today the

volcanic

scoria that surrounded the vent in 1831 have been planed off: to thirty metres deep. A column of rock twenty metres in diameter – the lava-choked neck of the old volcano – rises to a dangerous eight metres below sea level (and looks, one must suppose, rather like the conning tower of a submarine to the pilot of a B52). To a geologist it is just alkali olivine Hawaiite basalt, a typical piece of ocean floor. Most of our planet is covered in similar stuff. No wonder geologists

were so nonplussed by the public interest in this here-today-gonetomorrow island.

But in 1831 men of science exhibited no such disdain. Its

emergence

was greeted as an amazing prodigy, and the most advanced scientific thinkers of the time seized on it with glee. The man who founded the Société Géologique de France, Louis Constant Prévost, wrote a lengthy scientific paper about the island (which he called L’Isle Julia); though by the time it finally appeared in print, in 1835, the island itself had long vanished. Meanwhile in England there was another geologist for whom the movement of the Earth’s crust was a source of interest.

Charles Lyell is undoubtedly one of the most influential geologists who ever lived, even outstretching Suess’s shadow over subsequent ages. When you read Suess’s obituaries you are struck by the way all of them reach for comparisons; for writers with comparable scope, who published great books that will stand for ever as their monument. The one name they all quote is Charles Lyell, author of

Principles of Geology.

Through his

Principles

, which Darwin took aboard the

Beagle

as his bedtime reading, Lyell had come to dominate the way geologists (especially English geologists) in the nineteenth century thought about Earth history. He preached a strict version of a creed known as uniformitarianism, the concept credited with putting an end to wild speculation about the past and turning geology into a science.

So what is it? The essence of the principle is simple. It says that to understand what the rocks are trying to tell you, you should look around at the causes operating today and find an explanation among them. Geologists constrain their interpretations of the rock record by looking at the way the modern world works. The modern world is the control on geologists’ thought experiments.

This is how it works. If you were to see me in the street with a black

eye and grazed elbows, you could devise a number of possible scenarios to explain how I got that way. You might conclude I had been abducted by aliens and used as a guinea pig in their experiments. That explanation would not be uniformitarian because, although some pretty unusual things do happen in Stoke Newington, alien abductions are not among them. On the other hand you might

surmise

that after one glass of Pinot Grigio too many I had missed my footing and measured my length in the gutter. This

would

be a uniformitarian conclusion, because similar events happen almost every day (though not to me, you understand).

As well as urging present-day processes upon geologists,

uniformitarianism

also has something to say about their intensity. In addition to looking around for modern-day causes, the strict Lyellian assumption is that those processes have also always operated at a comparable rate. Thus deep time becomes paramount. The raindrop falling on the stone can, given enough time, move the mountain. Tiny changes, all but

imperceptible

to us, can achieve everything geologists might want because time is almost infinitely available. There is therefore no need to appeal to great upheavals or catastrophes; the gradual ups and downs of the Earth’s crust, as in the Baltic or the Graham Bank, will be enough.

This view of uniformity is an extreme one, but it was the

prevailing

view in Suess’s time, especially in England. The third (1834) edition of Lyell’s

Principles

devoted six pages to Graham Bank. It provided Lyell (who trained as a lawyer, and it showed) with a

convincing

courtroom argument against his catastrophist opponents. But Suess, who also subscribed to uniformitarian principles, had a different mind: one with mountains in it. Geologists who work among the world’s great ranges will tell you they leave an indelible stamp on the imagination. The Alps lay at the root of the Romantic revolution, as artists turned to them for inspiration. Mountains were no longer merely inconvenient obstacles but

meaningful

. Suess had

cut his geological teeth mapping the Alps and wrote an early book about them.

By contrast, Lyell hardly mentioned mountain building at all in his

magnum opus.

Today this seems very curious. It is almost as though he thought of mountains as a bit embarrassing, a sort of unsavoury fracas from which an English gentleman should avert his eyes. European

geologists

like Suess found the Alps much less easy to ignore. They knew in their bones that the Alps had something very important to say about the world and how it worked. Something about the beginning and the end of the world seemed locked up in their tumult.