Supercontinent: Ten Billion Years in the Life of Our Planet (6 page)

Read Supercontinent: Ten Billion Years in the Life of Our Planet Online

Authors: Ted Nield

The scholar Sumathi Ramaswamy dates the appearance of Sclater’s Lemuria in modern Tamil writings to the late 1890s, when Tamil authors first made the connection between it and the mythic

homeland,

of Kumarikkantam, sometimes even referring to this lost

continent

as ‘Ilemuriakkantam’. Modern science was being called upon to lend a picturesque Tamil myth the aura of literal truth.

The result of this process (which continues to this day) has been to set up a curious dichotomy. While academic historians in Tamilnadu do not necessarily believe in the literal truth of Katalakōl any more than their geologists might, among ordinary folk in Tamilnadu there is a commonly held belief that Western science ‘backs up’ the claims of their mythology. This continues to be implied, more or less overtly, in Tamil Studies.

Citing Sclater, Blanford and Haeckel, Tamil ‘devotees’ (as Ramaswamy terms them) thus imply (and in many cases openly claim) that the Tamil people are the ancestors of humanity and that their language is not only more ancient than Sanskrit (which is true), but is also the mother of all Dravidian tongues and even the oldest language of mankind. To put this into a more familiar English

context

, this is rather as if students of English were taught Arthurian texts with the clear implication that all that ‘sword and sorcery’ really happened. As Ramaswamy writes, this belief serves a political

purpose

: ‘The collective yearning for an unreclaimable past plenitude holds together a people in exile otherwise riven apart by caste, class and religious differences.’

However, there is a fly in the soothing ointment. The lost

supercontinent

of Lemuria never existed. The claim that it affirms the literal truth of the Tamil flood myth, via outmoded Western science, is an empty one. Science has moved on. By tying themselves to an unsustainable insistence on literal truth, Tamil’s devotees align

themselves

with outdated science, while at the same time depriving themselves of a more positive (overtly acknowledged) mythology. Myths, after all, can contain truths other than literal ones, truths that can be more fruitful. As Ramaswamy writes: ‘A mongrel formation,

neither pure fantasy nor respectable history, Tamil labours of loss are vulnerable to disavowal and dismissal both as fantasy and as history.’

Those familiar with the argumentation of so-called ‘creation

science

’ will find this philosophical bind oddly familiar. By insisting on the literal truth of the creation myth told in the Old Testament and by vainly looking for evidence of the supernatural among the things of this world, young-Earth creationists saddle themselves with a

similarly

impoverished mix. What they espouse is both bad science and bad religion, demonstrating nothing more than ignorance on the one hand and lack of faith on the other.

In Tamilnadu the conflict between modern science and an ancient myth propped up by the trappings of science (variously outmoded, selectively quoted or fraudulently misrepresented) rarely becomes apparent. One senses that those who know of the conflict (rather than purported accord) between myth and modern science see little

purpose

in challenging a widely believed misconception that does little practical harm.

However, every now and then political pronouncements can force the issue. In 1971 the Tamilnadu government decided to assemble a panel of scholars to ‘write the history of Tamilakam from ancient times to the present’. The education minister, R. Nedunceliyan, observed at the time: ‘When we say history, we mean from … the time of Lemuria that was seized by the ocean.’ That sort of thing can (and does) make scholars uncomfortable.

As Ramaswamy notes, this Tamil belief remains ‘eccentric’ within the culture of Tamilnadu. The spurious linkage of myth to science is confined to courses about Tamil, taught through the medium of Tamil, using textbooks produced by local publishers and the government-run textbook society, and catering predominantly for those (mainly less advantaged) people attending state schools. And so the belief persists, a hand-me-down textbook fact, immortal but (mostly) invisible.

Facing Sri Lanka across Palk Bay is the tip of India. Once dubbed Cape Comorin, it is now known by its original name of Kanyakumari. In the 1950s it became the subject of a concerted political effort to ensure that it was incorporated into the emergent Tamil state, which took its present form under the Madras presidency in 1969. ‘Kumari’ is a powerful name in Tamil. It is the name of the mythical lost continent itself. It is also the name of one of its

supposed

mountains, and also of a major river that supposedly crossed it. Kanyakumari is the only surviving real place still to bear this

heavily

loaded name; a last bastion against the cruel sea that tore the Tamil homeland from its people in Katalakōl. It plays the role of ‘a vestige of the vanished’.

Just a few hundred metres offshore is a tiny islet on which the Vivekananda Memorial now stands. It is composed of a rock called charnockite, a rock first identified in the tombstone of the first governor of Calcutta, Job Charnock (d. 1693), which was formed deep in the Earth’s crust 550 million years ago as two continental masses fused together. Geology does not admit to having sacred sites, but if it did, this would be one of them. For reasons that we shall explore later, geologists refer to this island as ‘Gondwana Junction’.

Like many of the world’s sacred sites, the islet is sacred to more than one group. On 26 December 2004, at nine o’clock in the

morning

, about five hundred pilgrims, mostly Indian, crowded on to the rock to stand at the Vivekananda Memorial and see the sun rise. Although they would not number among them, before that day was out, over 200,000 people all around the Indian Ocean would be dead. Many had already died; waves of destruction and death were

spreading

outwards, triggered by the biggest earthquake for fifty years, caused by the very processes that are forming the next supercontinent.

An event that has certainly happened before, and will just as certainly happen again, was about to overwhelm Tamilnadu.

Before Boxing Day 2004 the most recent Global Geophysical Event, which by definition affects (in some way) people on every

continent

, had been the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883. The Tsunami likewise had the effect of drawing the world together, but it also united Earth scientists in frustration that their knowledge had not been used to full effect, for example, to set up early-warning systems that had existed in the Pacific since the end of the Second World War. It also explained two things. It explained why Tamil people have an embedded myth of a dangerous and land-hungry sea that snatches life away in a catastrophic Katalakōl. And for me it explained why the seemingly abstruse subject of the Earth’s Supercontinent Cycle

matters

to everyone, everywhere.

But now is not the moment.

3

‘Some kind of legend from way back, which no one seriously believes in. Bit like Atlantis on Earth.’

DOUGLAS ADAMS,

THE HITCHHIKER’S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY

Philip Sclater’s hypothetical lost supercontinent, invoked to explain the scattered distribution of lemurs, was haunted right from the outset. But of all the strange settlers Lemuria attracted, none was stranger (or had wider influence) than Helena Petrovna Hahn.

Hahn (1831–91) was born in the southern Ukrainian city now known as Dnipropetrovsk but which was then known as Ekaterinoslav; she was the daughter of Pyotr Alexeyevich von Hahn, an army colonel, and his novelist wife Elena Fadeev. Elena, who had earned herself the literary sobriquet of ‘the Russian George Sand’, died when her daughter was only eleven. Although the family had moved around considerably, as army families do, her father was unable to take little Helena with him after her mother’s death so Pyotr Alexeyevich farmed her out to her maternal grandmother, Elena Pavlovna de Fadeev, she was nobly born, a well-known botanist, and another formidable character.

Helena Petrovna was to grow up to be one of the strangest women of the nineteenth century, going from sweatshop worker to bareback rider, professional pianist and finally co-founder and guru of a pop-

ular and once-influential new religion called Theosophy. Helena Petrovna was the first of the New Agers, and she derived the name by which the world knows her today from her first husband, General Nikifor Vassiliyevich Blavatsky.

Escaping from the General soon after the wedding by breaking a candlestick over his head and fleeing on horseback to Constantinople, Madame Blavatsky – after another very short marriage – set off to travel the world, ending up in 1873 in New York, where she set up as a medium. There she teamed up with Henry Steel Olcott (a lawyer who left his family for her) and others and founded the Theosophical Society, a new religion combining aspects of Hinduism and Buddhism. This new creed, she claimed, had come to her in a ‘secret doctrine’ passed down from an ancient brotherhood. Unlike those of the Rosicrucians and Freemasons, Blavatsky’s ancient brothers derived from Eastern rather than Western sources. And in common with many subsequent New Agers, Blavatsky claimed that her so-called Akashic Wisdom was consistent with science, and especially the then

fashionable

new science of evolutionary biology. This was a remarkable claim, since the scientific idea she most hated was the one that humans had evolved from apes. Madame Blavatsky had her own ideas about that and set her own distinctive account of human origins on landmasses that no longer existed. Lemuria, coming as it did with impeccable

scientific

credentials, fitted the bill perfectly, just as it had for Tamils.

Blavatsky had moved from America to India in 1879, and in 1882 she passed a number of letters from her late Master, Koot Hoomi Lal Sing, to an Anglo-Indian newspaper. (Graphologists later determined that she wrote them herself.) The cosmology contained in them was based on the number seven: seven planes of existence, roots of humanity, cycles of evolution and reincarnation. This scheme formed the basis for her book

The Secret Doctrine

, which became the main text of the Theosophical movement.

Before she could finish this opus, however, Blavatsky was hounded out of India. Two of her staff, Alexis and Emma Coulomb (who may well have been put up to it by Christian missionaries), threatened to expose her mystic feats as trickery, and Blavatsky returned to Europe, where she completed

The Secret Doctrine

in 1888. It ultimately derived, she wrote, from a ‘lost’ work called

The Stanzas of Dyzan.

According to these, modern humans were the fifth of the seven ‘root races’. The third race had inhabited the lost supercontinent of Lemuria, bandy-legged, egg-laying hermaphrodites, some of whom had eyes in the back of their heads and four arms (though perhaps not both at once).

The Lemurians had, according to Blavatsky, lived alongside dinosaurs. As if this was not exciting enough, they also discovered sex. This turned out to be A Bad Idea (for the Lemurians) because it was the trigger, Blavatsky believed, for the destruction of their

continent

. Their surviving offspring (the fourth ‘root race’) were the Atlanteans. It was they who wrote the

Stanzas

and who gave rise to the fifth race, namely us. Modern humans would eventually give way to the sixth and seventh races, who would inhabit North and South America respectively.

Blavatsky died in London in May 1891 from a chronic kidney

ailment

aggravated by a bout of influenza, and was cremated at Woking cemetery. Rather like Lemuria, the movement she founded soon split up and sank in schism and recrimination, never maintaining the

following

it commanded while its high priestess was alive. (It is estimated to have peaked at about 100,000 worldwide and is known to have included several influential and otherwise apparently sane people.)

Theosophy, pioneer of a genre, lives on, as does its conception of Lemuria, though largely on the ethereal plane of the World Wide Web.

The Indian Ocean had its Lemuria, and the Atlantic had of course its Atlantis. But what of the largest ocean of all, the last surviving

remnant

of Panthalassa? The potential financial rewards for this kind of work are great, as Blavatsky had shown; and as any scientific fraud or unscrupulous journalist knows, it is a lot quicker to make things up than find things out. Crucially too, the Pacific is the closest ocean to California, the best place in the world to found new religions. Madame Blavatsky herself recognized this, and in her later writings began edging her Lemuria out of the distant Indian Ocean and into the Pacific for this sound business reason. Yet despite her

tweakings

, the Pacific Ocean still represented a huge vacant lot to the would-be supercontinent maker, and before long one was duly ‘discovered’. The odd thing is, by the time its name broke upon the public in the twentieth century, it had already existed in the minds of (some) men for centuries.

Mu is perhaps the maddest of all imaginary lost continents. Its

origins

, however, lie not with the sciences of zoology, botany or geology, but with archaeology; and the very unscientific analysis of some very ancient writings.

Its existence was first proposed by one Charles Etienne, Abbé Brasseur de Bourbourg (1814–74). The Abbé travelled much of Europe and Central and South America in the service of the Catholic Church, and apart from missionary zeal his main life interest lay in the ethnography of the native peoples of America. In his later years he became convinced of pre-Columbian connections between American and Eastern races, connections for which the existence of the Pacific Ocean constituted something of a geographical snag.

The Mayans left very few written documents, and deciphering them has always presented acute difficulties in the absence of any

equivalent

of the Rosetta Stone that offers the linguist parallel texts of which

at least one is known. Nothing daunted, the Abbé set about the task of reading the Troano Codex. This codex consisted of half of one of three surviving Mayan manuscripts, and it is now part of what is today known as the Madrid Codex. In his reading he thought he

discovered

references to a sunken land by the name of Mu, and leapt at the idea because it solved his ethnographical problems by bridging the Pacific. So Mu started life, rather like Lemuria, as a means of

explaining

a distribution pattern – only this time, of people.

The Abbé’s references were next picked up by a widely (though uncritically) read Philadelphia lawyer and Minnesota congressman, Ignatius Donnelly (1831–1901), author of

Atlantis: the Antediluvian World

(1882). Unhappily for Donnelly, his literary judgement failed him over the de Bourbourg ‘translation’ of the Troano Codex on which he, the Abbé and the supposed continent of Mu depended. For the translation was, in fact, nothing of the sort.

De Bourbourg had ‘interpreted’ the Codex, having himself

discovered

a ‘Mayan alphabet’ devised by a Spanish monk by the name of Diego da Landa. Arriving in America with the Conquistadores, da Landa was among the first scholars to come across the vivid

pictograms

of the Mayan people. His so-called alphabet was nonsense; the Mayan writing system was not letter-based at all.

The Abbé’s Troano Codex ‘translation’, which supposedly described (in highly elliptical terms) some great volcanic catastrophe, was nothing more than a figment of the Abbé’s fevered imagination, spurred on by the application of da Landa’s bogus alphabet. And, crucially for this story, during the process of his creative decipherment de Bourbourg came across two pictograms that he could not at first identify. Thinking, though, that they bore a slight resemblance to the symbols that da Landa asserted to be the Mayan equivalents of the letters M and U, the Abbé duly discovered the name of the ill-fated continent. Thus was Mu born.

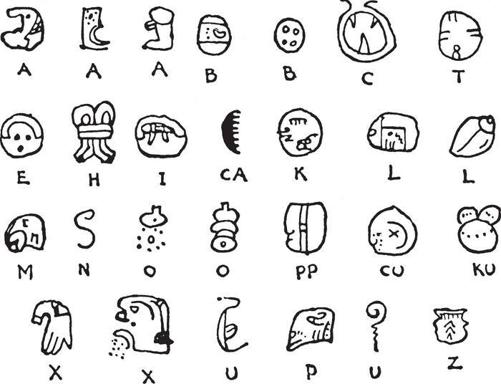

The supposed ‘Mayan Alphabet’.

Back in Washington, unaware of how rotten its foundations were, Ignatius Donnelly took the Mu story on. In his book he linked this entirely bogus Mayan legend with Plato’s allegorical Atlantis and went on to speculate about how this connection might shed light on archaeological links between the Mayan and other civilizations. And there the Mu legend paused, until one Colonel Churchward picked it up and moved it back into the Pacific.

Colonel James Churchward (1851–1936) stares winningly out of his picture like a cross between Colonel Sanders and a travelling

medicine

man peddling potions in a Hollywood Western. He sports a rakish goatee and moustache, and wears a large rose in his left lapel. Although he had written a book before, namely

A Big Game and

Fishing Guide to North-Eastern Maine,

this gasconading English émigré shot to literary success rather late in life with his colourful accounts of a huge continent lost below the Pacific.

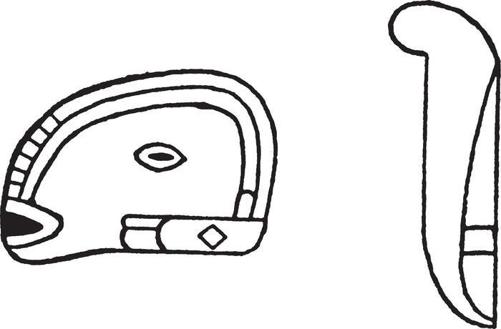

The two ideograms thought, from tenuous supposed similarities to characters in the supposed alphabet, to represent the letters M and U.

The Lost Continent of Mu

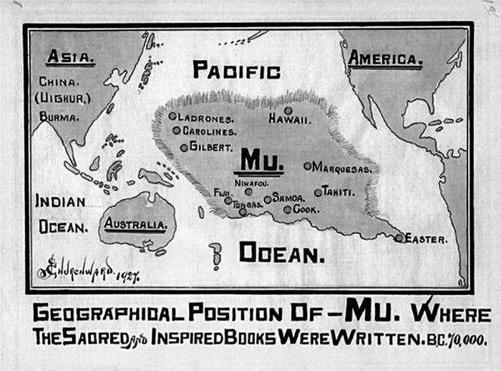

(1926) set out Churchward’s claim to have discovered the tale of Mu and its destruction in mysterious ancient texts. He claimed the continent had sunk about 60,000 years ago and that Easter Island, Hawaii, Tahiti and a few other Pacific islands were its last remnants. This information he gleaned from the ‘Naacal Tablets’, having himself been taught the Naacal language by a Hindu priest in India in 1866. (Churchward’s military rank was said to have been gained in the British Army in India, but this too is unconfirmed.) As well as the tablets of Naacal, Churchward gleaned information from a different set of tablets found in Mexico by one William Niven, who is variously described as a geologist and engineer. No one else has ever seen these tablets either.

The lost continent of Mu as envisaged by Churchward.