Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (54 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

We also attended meetings with other Palestinian factions, including Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), although we hadn’t been informed they were in the offing before our arrival in Damascus. I checked on the Internet after our surprise meeting with Ramadan Shallah, general secretary of the PIJ, and found him on the FBI’s most-wanted terrorist list, with a $5 million reward for information leading to his arrest or conviction, and so I related our discussions to U.S. authorities. No doubt those we met in Damascus assumed we would be reporting back.

The WFS delegation was also tasked with probing the plausibility and potential significance of material cooperation on “economic” projects—such as solutions to regional problems of water, energy, and the environment—in seeking novel and productive pathways to resolving long-standing conflicts. All Syrian and Palestinian leaders we talked to rejected any economic cooperation before a peace settlement was reached. No support emerged forthe idea that economic cooperation could help resolve the region’s deep-seated conflicts without first addressing perceived threats to core values. As Syria’s Foreign Minister Walid Muaellem said:

“Mr. Netanyahu says to us and the Palestinians: ‘Let’s concentrate on economic relations but not on who has sovereignty over the land.’ But sovereignty over land is the key to this region, because it is for Arabs a question of honor and dignity, ‘

Ard wal ard’

[Land is honor].”

In regard to Hamas, the principal question that interested Israel was:

“Is there any possibility that Hamas could ever recognize Israel, not necessarily now but in the future, under whatever conditions? And if so, what would Hamas want for it?”

In a previous visit to Damascus, Israeli leaders told me beforehand that a positive response would, in their minds, represent a “strategic shift” in Hamas’s attitude and hence justify engaging Hamas as a potential partner in peace. Some in Hamas had answered “perhaps” and others “no.” But this time Khaled Meshaal, chairman of the Hamas Politburo, pointedly rejected the question about the future possibility of Hamas recognizing Israel as being inappropriate because it ignores basic asymmetries in: (1) existing rights between Israelis and Palestinians (which violates the core value of “dignity”), and (2) the current balance of forces and power:

Why is this question always the first question being asked? It is a question that requires that the Palestinians make the first concession. It does not speak to Palestinian rights at all. The basic rights of Palestinian people must first be recognized: to live without violence, without killing, without siege or arrest, to have hope without occupation. There is not much discussion from the other side about this. Nobody asks Israel if they will first recognize us…. The Israelis have rights, but we also have rights; no one can have the exclusive right to basic rights.

Meshaal then went on to outline Hamas’s conditions for the proper time and context to pose the question of recognition:

After Israel withdraws to the 1967 borders, and there is a Palestinian state with full and complete sovereignty with its capital in East Jerusalem, and the issue of the refugees is settled, then you can ask your question again and we will have a different answer. If a sovereign Palestinian state chooses to recognize Israel, Hamas would accept that choice.

Only a sovereign Palestinian could recognize Israel. Why? Because you must have complete freedom to make the decision. You can’t ask a person in prison, of his own free will, to recognize the rights of his jailers, when the prisoner’s rights are ignored and not guaranteed. You can’t expect the prisoner under torture to be satisfied talking about financial arrangements with the jailer. To achieve normal relations, there has to be a referendum to make the decision. It has to be the choice of the people.

Khaled Meshaal comes off as a natural leader, with more authority and charisma than any other Palestinian leader I’ve met. He could be humorous and self-deprecating. Unlike less commanding leaders, he made no attempt to show how important he was by taking calls, or allowing aides to interrupt him with other business, and his pontifications were kept short. He did not seem to personally begrudge Israeli prime minister Netanyahu an earlier assassination attempt by poisoning, which had almost killed him. Meshaal was straightforward without being arrogant and did not appear on the surface to be a schemer or duplicitous, although his intelligence and physical control are nuanced enough to be able to craft deception. He projected confidence in ultimate victory, although as Bob Axelrod surmised, “even a cursory analysis of his strategy would suggest it will take a long war of attrition to have a chance to work.”

Meshaal made it clear that he had no interest in global jihad: “I’m not affiliated with a global movement, but I can understand the anger that has led others to it. The response of others who are oppressed and who created Al Qaeda is sometimes exaggerated and irrational. We are a resistance movement against an occupation. We haven’t made any operation outside Palestine. We have never sought to kill a Jew because he was a Jew. We don’t fight America.”

But perhaps the most interesting question I posed to Meshaal was: “In your heart, do feel that peace—

salaam

—with Israel is possible? … Be as sincere as you can, personally.” According to his own aides, Meshaal was surprised by the question, which he supposedly had never heard before, and they were surprised by his answer:

“The heart is different from the mind, and the mind resists by all logic, but the heart says yes. In my heart, I feel peace—

salaam—

with Israel is possible. But when we have a balance of power … to force Israel to keep to its commitments.”

The word

salaam

(peace) was used in the question, and

salaam

was used in the answer. The Hamas watchword

hudna

(armistice) never came up. By contrast, PIJ’s Ramadan, who believes Hamas shares his goal of repossessing Israel but is too “tactically conciliatory in proposing a long-term

hudna,”

responded: “Never, ever.”

I also asked Meshaal: “Suppose Israel were to make a unilateral no-cost concession, like apologizing for part of the suffering caused by the dislocation and dispossession of the Palestinian people in 1948. Would that mean something to you?”

His answer, like Marzook’s, was that such words would “mean something, but aren’t enough:”

They are important, even if they are only words, if they are sincere…. Our religions say “the world began with the word”and wars start with words…. In my heart, I can understand the search for signals to exchange and keenness to see lights on the horizon. But for eighteen years since [the] Madrid [Conference] we’ve tried every medicine, every surgery. Now, words would not be enough to keep the patient alive. I wish it were that simple. The key is the balance of forces that creates conditions for peace…. We will not be second-class citizens.

Understanding sacred values isn’t about a group hug. It’s about understanding human nature—what it is to be human. With sacred values, cost-benefit calculus is turned on its head, and business-style negotiations can backfire. Asking the other side to compromise a sacred value by offering material concessions can be interpreted as an insult and make matters worse, not better. Surprisingly, however, our studies and discussions with political leaders indicate that even materially intangible symbolic gestures that show respect for the other side and its core values may open the door to dialogue and negotiation in the worst of conflicts.

Apologies and shows of respect acknowledge the dignity of others and can speak to other people’s sacred values. But it’s often terribly painful to make these and other symbolic gestures and then, having made them, to have them accepted as sincere by your adversary without risking a serious backlash at home. That’s why it generally takes someone with sufficient power or reputation, like Anwar Sadat or Nelson Mandela, to make such moves.

Finding ways to reframe cultural core values so as to overcome psychological barriers to symbolic offerings that show respect for the other side’s sacred values is a daunting challenge. But meeting this challenge may offer greater opportunities for breakthroughs to peace than hitherto realized. “Mere” words and symbols may prove more powerful than billions of dollars in aid or bombs and bullets—at least in opening up opportunities for practical solutions. Though difficult, creatively reframing sacred values mayprovide a key to unlocking the most deep-seated conflicts. That’s the kind of insight that the anthropology and psychology of religion and sacred values could bring about. There may be few more urgent fields of study in the world today than “the science of the sacred.”

Part VII

THE DIVINE DREAM AND THE COLLAPSE OF CULTURES

Le XXIème siècle sera religieux ou ne sera pas—

The 21st century will be religious or will not be.

The greatest mystery is not that we have been flung at random among the profusion of the earth and the galaxies, but that in this prison we can fashion images sufficiently powerful to deny our nothingness.

—ANDRÉ MALRAUX, ANTIFASCIST, ANTICOMMUNIST SECULAR

FRENCH ELITIST, 1901–1976

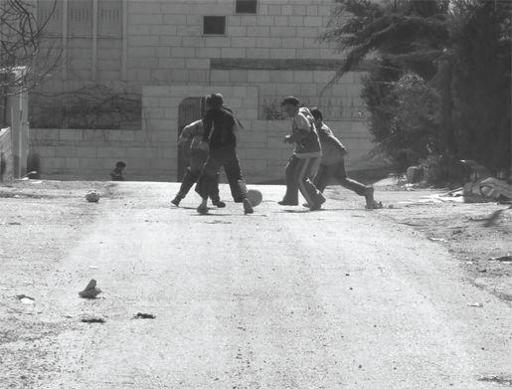

Soccer buddies in Hebron’s Wad Abu Katila neighborhood.

CHAPTER 22

BAD FAITH: THE NEW ATHEIST SALVATION

Greater love hath no man than this: that he lay down his life for his friends.

—JOHN 15:13

HEBRON, WEST BANK, FEBRUARY 2008

At five

A.M.

on February 4, 2008, twenty-year-old Mohammed Herbawi and his close friend and soccer buddy Shadi Zghayer silently left their homes in the West Bank city of Hebron on a suicide bombing mission across the Green Line to Israel. As always with this sort of thing, parents were left completely in the dark. At ten

A.M.

, one of the young men managed to detonate his vest near a toy store in a shopping center in Dimona, a small town that houses Israel’s secret nuclear program, killing seventy-three-year-old Lyubov Razdolskaya and wounding forty others. Lyubov had been on her way to the bank along with her husband, Edward Gedalin, who was critically wounded. The couple immigrated to Israel from Russia in 1990, and worked in the physics department of BenGurion University until they retired in 2002. They were shortly to have celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary.

Hamas took responsibility for the Dimona attack—the first suicide attack claimed by Hamas since it suspended “martyrdom actions” in December 2004—after Fateh’s Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades had first claimed it for their own. But the Hamas politburo in Damascus clearly didn’t order it or even know about it. OsamaHamdan, the de facto Hamas foreign minister headquartered in Beirut, initially said he had no idea who was responsible. When I asked senior Hamas leaders in the West Bank if this meant that the political leadership in exile didn’t know about the attack, they said, “Yes, you can conclude that; we certainly didn’t.”

I went to Hebron on February 9, 2008, to interview friends and families of the two young men who carried out the Dimona attack. These two friends were members of the same Hamas neighborhood soccer team as a number of others who died in suicide attacks: the Masjad (mosque) Al Jihad soccer team located in the neighborhood of Wad Abu Katila, with participation also from members of the Masjad al-Rabat team. Wad Abu Katila is a residential quarter of 7,000 to 8,000 people, neither rich nor poor but with lots of unfinished construction because of the collapse of the Palestinian economy during the Second Intifada. Several on the team also attended, or had planned to attend, the local Palestine Polytechnic University.

Basma Hamori was waiting for me at the top of the stairs with her son Ahmed, Mohammed Herbawi’s younger brother. She was divorced from her sons’ father and worked in a child-care center. I came with the Associated Press stringer who had sent in his dispatch reporting that Basma and Shadi’s mother, Ayiza, were proud of their sons, who would go to heaven. Almost all mothers of suicide bombers will say this to reporters on a first account. But when I ask the mothers and fathers, “Would you want any of your other children to do it?” almost all say, as did Basma, “Not for all the world,” or other words of that sort.

Other books

Spell Fade by J. Daniel Layfield

Echoes by Christine Grey

While the World Watched by Carolyn McKinstry

Blessed Child by Ted Dekker

Bloodsong by Eden Bradley

The Invisible Papers by Agostino Scafidi

Cry Me A River by Ernest Hill

Dangerous (Courting the Darkness Saga) by Fuller, Karen

His to Have (A Claimed Story Book 2) by Jade Sinner