Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (55 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

I questioned the reporter just before entering Basma’s apartment: “Have you ever met a mother who is happy about something

like this?”

“No,” the reporter answered, “but our society respects martyrs.”

“Do you think it’s because of the religion?” I asked.

“I’m not religious and I respect them. It’s a terrible thing for a right cause, recognition of our rights. At least it gets the Israelis to recognize we exist.”

Basma asked Ahmed to bring cookies and coffee. “I don’t understand, I don’t believe he died.” Basma’s eyes, you could see, were shot from days of crying. She quietly insisted with a weary voice: “If only I would have known, I am against it, against it.”

“You see,” she held up a picture of her cell phone with Mohammed’s picture. “He’s still with me.” Her face resembled a frightened doe’s. “He’s always with me. I can’t believe he’s not alive. I would have looked at him, talked to him, pleaded with him, cried and begged him not to do it. And he would have listened to me. That’s why he didn’t tell me, because he knew he couldn’t resist a mother’s influence, which is the strongest influence in a boy’s life. That’s why they never tell their mothers.”

Ahmed suddenly left the room. He was fifteen, in the tenth grade, the same age as when his brother was arrested (another brother, nineteen-year-old Muntaz, was serving a one-year prison sentence for belonging to Hamas). Ahmed soon returned with two stacks of posters, wall-size and smaller folio-size. He offered them with resignation and pride.

“This is my brother,” as if to show me, and himself, that there was still something alive and substantial left of his brother.

I took a small one.

“He was a star for the team.” Ahmed’s eyes, strained beyond their years, sparkled for a second. “Sometimes he would be the goalie, sometimes a striker.”

I nodded.

“Ana hazin”

[I am sad]. He plopped back down on the couch, deflated.

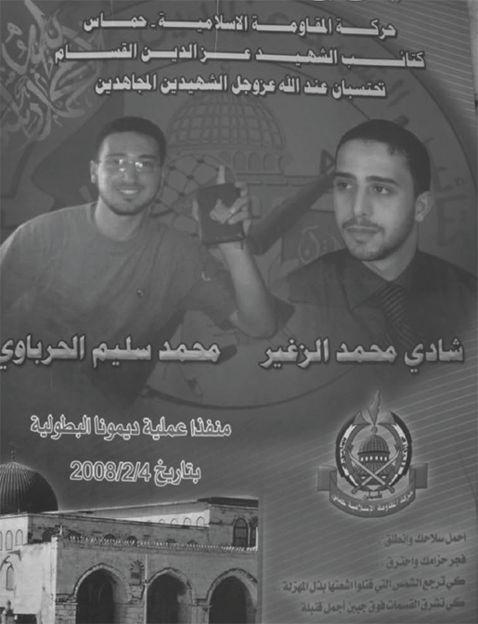

The poster with the seal of Hamas’s Qassam Brigades read: “You took your rifle and went. You blew up your belt and burned. So as the son that they killed would rise up again.”

Hamas poster of martyrs Mohammed Herbawi (left) and Shadi Zghayer.

Basma looked at the smiling image of her son (on the left) and she, too, smiled ever so faintly. “The Israelis kept him in prison for two and a half years. When he came out, he still loved soccer. He still loved those boys. And then there was the divorce. He worked hard and gave me most of the money. My job at the day-care center doesn’t give enough. Maybe it was too hard on him, all of it.”

“And all those boys played soccer?” I asked.

“Yes, and the others who became martyrs before, some boyson the senior team. He [Mohammed] was only fifteen then, in the tenth grade, but he was arrested just after Muhsein Qawasmeh and some of the other boys he played soccer with became martyrs. The Americans and Israelis want us to leave our land. The boys are telling them we don’t want to leave. But theirs is not the way. That way is crazy

[majnun].

God, let them leave us alone.”

Across town, the backyard of Fellah Nasser ed-Din, former imam of the Hamas-affiliated Al Jihad mosque for fifteen years and the sometime coach of its soccer team, is blessed with a magnificent view of the Hebron hills and littered with the carcasses of cell phones (about 125,000,000 cell phones are discarded worldwide every year, a piddling part of globalization’s garbage, but particularly evident in the developing world, where waste is out in the open).

“Muhsein was the brightest of the bunch,” Nasser ed-Din told me. “He was an outstanding student, 99 percent, always first in school. The young boys in the mosque would gather around him. He taught them religion and soccer. He was beloved. He was energetic, even charismatic, but no extremist. I never saw any hint of violence in him.”

“Why, then, do you think he went out to kill?” I asked.

“In his last year in high school—I talked to him about his studies and knew him well—he changed. His family also came to me and said he wasn’t focusing on his lessons.”

“And the other boys who went out to kill and died?”

“Muhsein, Hazem, Fadi, and Fuad were close friends from Wad Abu Katila [a once middle-class neighborhood in increasingly impoverished Hebron].” Soft-spoken, they were all good students, good looking, and from good families. Basma also lived close by.

“They all loved soccer. I love soccer.” The coach beamed. “Let me show you something.”

Fellah Nasser ed-Din rushed into his house and was out in a flash with two stacks of photo albums under his arms.

“Here I am as a boy on my school team,” he said, clearly proud and happy with his memories. “And here I was a coach. See. Yes, those boys were all good players, but Muhsein was their natural leader. He was a good organizer, small like [the Argentinean soccer star Diego] Maradona. His mother is a schoolteacher and raised him well. His family had a bookstore. He was the smartest of all.”

“Did he organize the team or the attacks?” I asked.

“No, no. It’s not like that. There’s no team captain or coach. They organized themselves. They even organized matches with fifteen other local teams in honor of fallen martyrs. Sports means cooperation, caring, and tolerance for other players, and in this spirit they also organized themselves in prayer and in discussions about religion, and in thinking of ways to help their community overcome the restrictions, the suffering, the blood. They found their own way.”

And then he added: “People don’t have much trouble finding one another for actions like this. We’ve been fighting the Jews for a century and we’ll go on fighting until we win our dignity and land back. All of it. As long as we’re one team (ma

domna fariq wahid)”

THE END OF FAITH AND OTHER PULP FICTION

In the best-seller

The End of Faith: Religion, Terrorism and the Future of Reason,

1

Sam Harris, a graduate student in neuroscience with remarkable polemical skills, pulls no punches in deference to the tender religious sensibilities of others. (God help us, now that academic pundits have suddenly discovered we are all faced with the end of faith, end of history, end of evil, end of poverty, end of the nation-state, end of life, and so on.) Harris bemoans the destructive nature of religion and implores all people with any modicum of reason to fight against it. In the spirit of philosopher Dan Dennett’s

Breaking the Spell,

2

Vanity Fair

contributor ChristopherHitchens’s

God Is Not Great,

3

and biologist Richard Dawkins’s blockbuster

The God Delusion,

4

Harris insists that secular moderation toward religion and ecumenical tolerance only enable bizarre and belligerent beliefs to thrive and extremists to flourish, with cruel and savage consequences for the world. It is stated almost as a law of nature. Later, I’ll discuss the science, or rather lack of science, behind this missionary call. Here I only want to introduce some common misconceptions about suicide bombers and Muslims that have reached hysterical proportions.

Harris begins his book with a vivid anecdote that he presents to the reader as commonsense fact:

The young man takes his seat beside a middle-aged couple…. The young man smiles. With the press of a button he destroys himself, the couple at his side, and twenty others on the bus. The nails, ball bearings, and rat poison ensure further casualties on the street and in the surrounding cars. All has gone according to plan.

The young man’s parents soon learn of his fate. Although saddened to have lost a son, they feel tremendous pride at his accomplishment. They know that he has gone to heaven and prepared the way for them to follow. He has also sent his victims to hell for eternity. It is a double victory.

These are the facts. This is all we know for certain about the young man…. Why is it so easy, then, so trivially easy—you-could-almost-bet-your-life-on-it easy—to guess the young man’s religion?

The lesson drawn from juxtaposing this observation with the suicide attacks of September 11 is that “we can no longer ignore the fact that billions of our neighbors believe in the metaphysics of martyrdom, [and] are now armed with chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons…. We are at war with Islam. It may not serveour immediate foreign policy objectives for our political leaders to openly acknowledge this fact, but it is unambiguously so.” Harris and others in the fellowship that Christopher Hitchens calls the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (Harris, Hitchens, Dawkins, and Dennett) see science at the front line of this necessary and inevitable struggle against Islam in particular, and religion in general. No joke.

First some contrary facts: Suicide bombers are not only Islamic or religiously motivated. In fact, until 2001 the single most prolific group of suicide attackers had been the Tamil Tigers of Sri Lanka, an avowedly secular movement of national liberation whose supporters are nominally Hindu. In the Middle East before 2001, most suicide bombings occurred in Lebanon, and about half were by secular nationalists (Syrian Nationalist Party, Lebanese Communist Party, Lebanese Ba’ath Party).

5

True, since 2001 the overwhelming majority of suicide attacks have been sponsored by militant Muslim groups, but there isn’t much precedent in Islamic tradition for suicide terrorism. Modern suicide terrorism became a political force with the atheist anarchist movement that began at the end of the nineteenth century, which resembles the jihadi movement in many other ways.

As for the “tremendous pride” that invariably trumps parental love, I have yet to meet parents who would not have done anything in their power to stop their child from such an act, though none of the dozens I’ve talked to ever knew, and few ever imagined, that their child could do such a thing. In history, psychology, and political-science classes, one regularly hears that Spartan and samurai mothers smiled when told their sons had died in battle. As Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker once wryly noted, of course there’s no record of a Spartan or samurai mother ever writing such a thing; we just have to take the leaders’ words for it. I’ve gone to homes where the press has reported that the parents were happy and proud of their son. I’ve heard the interviewing journalists ask,with the crowd and officials around, “Were you proud and happy?” Sometimes the parents say they are. What are they going to say when first informed of their child’s death? That it was senseless and stupid? That goes against people’s innate inclinations to give a sense to any heart-wrenching loss. Never have I heard a

shaheed

’s parent say,

in private,

“I am happy” or even “I am proud.”

In

Letter to a Christian Nation,

Harris goes on to lambaste believers of all faiths, though he still has an itch in his craw for Islam: “Seventy percent of the inmates of France’s jails, for instance, are Muslims. The Muslims of Western Europe are not atheists…. An atheist is a person who believes that the murder of a single little girl—even once in a million years—casts doubt upon the idea of a benevolent God.”

6

The implied logic—that religious people in general, and Muslims in particular, tend to do more terrible things than do atheists—is hollow.

As we saw in chapter 16, immigrant Muslims in America tend to be slightly more religious than non-Muslims, but are underrepresented in U.S. prisons relative to their numbers in the general population. The predictive factors for Muslims entering European prisons are pretty much the same as for African Americans (religious or atheist) entering U.S. prisons: underemployment, poor schooling, and political marginalization. Controlling for population sizes, Muslims are about six times more likely to be arrested for jihadi activity in Europe than in America,

7

although the political pressure on law enforcement to get more arrests is greater in America (given “zero tolerance” in U.S. law enforcement for anything related to jihadi activity). But even in Europe, the more someone is exposed to Muslim religious education, the less likely he or she is to enter prison.

Other books

Until Then (Cornerstone Book 2) by Noorman, Krista

American Tempest by Harlow Giles Unger

Five Quarters of the Orange by Joanne Harris

Ireta 02 - [Dinosaur Planet 02] - Dinosaur Planet Survivors by Anne McCaffrey

Uglies by Scott Westerfeld

The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future by Joseph E. Stiglitz

Edge (Gentry Boys #7) by Cora Brent

Abel by Reyes, Elizabeth

Uncle John’s Fast-Acting Long-Lasting Bathroom Reader by Michael Brunsfeld

Isle of Wysteria: The Monolith Crumbles by Aaron Lee Yeager