Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (26 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

At first, it seemed as if the Chinaman might be slipping back into his old life. He’d left the Afghan tunic behind for short-sleeved shirts and jeans again. He beat up guys who owed him drug money, but he also told his old friends, “Don’t drink, don’t go to bars, don’t take drugs.” He went back to dealing drugs with his friend Abdelilah, though he shied away from alcohol and taking drugs himself. Abdelilah was running the drug operation now, not the Chinaman. The Chinaman’s heart just didn’t seem to be in it anymore. “Then, like in September or October, I started hearing about Serhane, the Tunisian, and Jamal began to change,” Rosa said. “He didn’t touch me anymore…. My mother’s ex-boyfriend, who was with him because he took care of his cars [the Chinaman still had plenty of money from the drug business], told me, ‘Rosa, there is somebody who is eating his brain; he talks about him the whole day. Be careful, because he is telling Jamal [to get rid of] ‘that Spanish girl.’”

The Afghan, Abdennabi Kounjaa, and the Kid, Asri Rifaat Anouar.

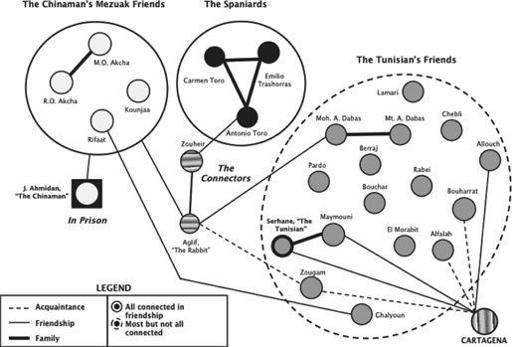

When and how the Chinaman and the Tunisian connected is unclear, but their respective social networks overlapped considerably, and there were numerous possible pathways for them to link up. One was through the many everyday interactions in the Lavapies neighborhood. The Chinaman would deal drugs in the Plaza Cabaste-ros and sometimes stop by the halal butcher shop owned by the family of his friend Rachid Aglif, a delinquent nicknamed “the Rabbit” (el Conejo) because of his elongated face and big front teeth. He’d walk down Tribulete Street past Jamal Zougam’s phone-and-Internet shop on the way to the Alhambra restaurant, where just about everyone in the neighborhood would eat and chat on occasion, including the Tunisian. At the nearby barbershop, they’d discuss the world while their hair was cut, and make ablutions and pray there too.

The Chinaman’s most loyal pals, Mohammed and Rachid Oulad Akcha, would sometimes also pray at the Alonso Cano mosque, located in a fancier neighborhood. (The mosque was just an apartment: There are many such “mosques” in European cities, with no obvious outward signs to mark them. When we talked with people on Alonso Cano Street, no one who wasn’t Muslim was even aware of the mosque’s existence, including people who had lived nearby for decades.) At Alonso Cano, the Tunisian, who had by now acquired a reputation in Madrid’s North African community as a radical firebrand, preached the kind of things that the Oulad Akchas knew the Chinaman would appreciate. Also, in front of the Oulad Akchas’ house in Villaverde, people from both the Tunisian’s and the Chinaman’s circles would play soccer together, and sometimes pray in the nearby mosque where Cartagena had preached (though referred to as a “substitute imam,” he was actually a

da’i,

an unordained and informal preacher as the Tunisian had now become).

Two other buddies from Mezuak who would play an important part in the plot came to be tightly woven into these overlapping social networks: Abdennabi Kounjaa’, who was known in Mezuak as that neighborhood’s “first Afghan,” and Asri Rifaat Anouar, a slight and gentle vendor of candies whom people simply called “the Kid” (el Niño). Everyone I’ve talked to in Mezuak says Rifaat didn’t have a religious bone in his body until he hooked up with Kounjaa’. Rifaat’s family seems thoroughly secular, like the Oulad Akcha family. Rifaat’s sisters were known in the neighborhood as “moderns” who wore short skirts and liked

la mode

(French “fashion”). But Rifaat was drawn to the manly, bearded, brooding preacher who was Kounjaa’. Rifaat fell into jihad because he first fell for Kounjaa’. Rifaat, it appears, was gay (semen samples from a bed show Rifaat’s mingled with another man’s); however, there’s nothing to suggest that Kounjaa’, who was married, had anything more than feelings of fraternal affection and responsibility for the Kid.

As the Tunisian radicalized at makeshift mosques and soccer picnics in Madrid, so Kounjaa’ radicalized at the Dawa Tabligh mosque in Mezuak (also known as al-Rohbane), and at the soccer outings nearby. He would go out to some of the less radical mosques in Mezuak and adjacent neighborhoods to distribute tracts extolling the Salafi way, calling for jihad, and denouncing the Justice and Charity movement in Morocco as a Sufi heresy, impure and un-Muslim. In Mezuak, he alone of the Madrid plotters is remembered as being intensely religious, and many who knew both the Chinaman and Kounjaa’ (and being unfamiliar with the Tunisian) believe it could only have been Kounjaa’ who inspired the plot and the martyrdom after. Although the Chinaman and Kounjaa’ went to the same grade school and high school and lived within a few hundred meters of one another, by the time of their manhood they inhabited two different worlds, the criminal and the religious, until they joined up in Madrid.

Kounjaa’ and Rifaat showed up in Madrid around 2002. Like many Moroccan immigrants, especially the illegals, Kounjaa’ became a construction worker, where he hooked up with Rachid Oulad Akcha, one of the homeboys from Mezuak, and became involved in the drug trading network of the Oulad Akchas. (The Chinaman was in jail in Morocco.) One reason Rifaat came to Madrid was that he thought it would be easier to make his way to his mother’s relatives in Belgium from there. Rifaat’s own mother had died, and home was never the same once his father took a second wife.

Rifaat drifted closer to religion and did charity work helping out other immigrants. People liked him. Around 2003, Basel Ghalyoun, the Tunisian’s friend, was apparently touched by Rifaat’s sincerity and took the Kid under his wing.

9

By the time the Chinaman returned to Madrid from his prison stint in Morocco, the Mezuak homeboys had already merged socially with the Tunisian’s circle. When the Tunisian and the Chinaman finally met, all became energized. Rifaat, some say, fell head over heels in love with the Chinaman. He would go on to kill and die for an unrequited passion that came to embrace the whole Muslim world.

THE CONNECTOR, THE RABBIT, AND THE THREE SPANISH STOOGES

Ahmidan’s friend and suspected fellow drug peddler, Rachid Aglif, “the Rabbit,” worked in the family butcher shop in Lavapies. Aglif put the Chinaman in touch with a wheeler-dealer, Rafa Zouheir, who had known Aglif since the Rabbit first came to Spain from Morocco. Zouheir, a part-time nightclub bouncer and exotic dancer, had a long string of arrests, ranging from aggravated assault and arms trafficking to car theft and narcotics. In 2001 he was arrested for robbing a jewelry store in Spain’s northern province of Asturias and landed in a prison cell with a Spaniard, Antonio Toro, who had been jailed for illegal possession of hashish and explosives.

Toro introduced Zouheir to his cousin, another convict, named Emilio Trashorras, who was looking to sell explosives filched from the Conchita mines in Asturias where he and Toro sometimes worked. All three ex-cons were also informers who ratted on friends and acquaintances to help get themselves out of their frequent troubles with police.

The Connector, Rafa Zouheir; the Rabbit, Ra chid Aglif; and the three Spaniards, Antonio Toro, Emilio Trashorras, and Carmen Toro-Trashorras.

In May 2003, Zouheir’s handler, Victor (a captain in the judicial police, Unidad Central Operativa), told his charge to return to Asturias to contact the Spaniards about finding new customers for the explosives. In late September or early October, around the time the Chinaman connected with the Tunisian, the Chinaman let the Rabbit know that he was looking for explosives. The Rabbit turned to Zouheir, who had been hinting around at the Flowers whorehouse north of Madrid, where the two often went, that he was looking for clients to buy explosives. And so Zouheir became the plot’s Connector.

On October 28, 2003, the Connector, the Rabbit, the Chinaman, and his loyal buddy, Mohammed Oulad Akcha, met at the McDonald’s restaurant in the Carabanchel neighborhood of Madrid with the plot’s three Spanish stooges: Emilio, his cousin Antonio, and Carmen Toro, a department-store security agent who was Antonio’s sister and Emilio’s fiancée. The Spaniards called the Chinaman “Mowgli” after the darling nature boy of

The Jungle Book,

Disney’s film adaptation of the Rudyard Kipling classic. Behind his back, they called him and his friends “the Moors.”

The Moroccans agreed to give the Spaniards 35 kilos of hash in exchange for 200 kilos of dynamite and detonators and a bit of money. Playing with the detonators one day, the Connector almost blew off his hands as the Rabbit watched. But the hospital report didn’t raise eyebrows until after the trains were bombed.

For the first delivery, Emilio instructed his courier to tell the Moors that the money “was stolen” on the bus from Asturias to Madrid. The Chinaman greeted the courier at the bus station, listened to the courier’s baloney, then beat him to a bloody pulp and stripped him of everything, including his clothes. From then on, relations between the Spaniards and the Moors were civil and correct, complaisant even.

It’s doubtful that the Rabbit, the Connector, or the Three Stooges knew anything about the jihadi nature of the plot they were getting into, or that they even cared to know.

In November 2003, one of the Oulad Akchas, Khalid, who was in prison in Salamanca on drug charges, called his brothers Rachid and Mohammed in Madrid. The Chinaman answered the phone.

10

Khalid suspected something dangerous afoot involving his brothers and warned the Chinaman to stay away from them. But to the Chinaman, warnings were like a red cape flashing in front of a bull.

Three main circles of friends who will become involved in the Madrid Plot (summer 2003).

CHAPTER 12

LOOKING FOR AL QAEDA

T

hrough a series of unplanned events, two young North African immigrants bonded to plot an attack in Spain. They lived in separate worlds—religious extremism and the criminal underworld—until their paths crossed six months before the bombing. A detailed plot only began to coalesce in late December 2003, shortly after the Internet tract “Iraqi Jihad, Hopes and Risks” circulated on a Zarqawi-affiliated Web site. The tract called for “two or three attacks … to exploit the coming general elections in Spain in March 2004.” The plot—which brought together a bunch of radical students and hangers-on, drug traffickers, small-time dealers in stolen goods, and other sorts of petty criminals—improbably succeeded precisely because it was so improbable. There was no ingenious cell structure, no hierarchy, no recruitment, no brainwashing, no coherent organization, no Al Qaeda. Yet this half-baked conspiracy, concocted in a few months, with a target likely suggested over the Internet, was the immediate cause of regime change in a major democratic society.

Other books

Salvation and Secrets by L A Cotton

When My Name Was Keoko by Linda Sue Park

Eleven Kinds of Loneliness by Richard Yates

Guide Me Home by Kim Vogel Sawyer

OnLocation by Sindra van Yssel

Racing to Love: Eli's Honor by Amy Gregory

The Glass Highway by Loren D. Estleman

Unraveled Together by Wendy Leigh

Merian C. Cooper's King Kong by Joe DeVito

The Boy Who Knew Everything by Victoria Forester