Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (30 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

“Of course we have to find out what’s going on, but the families are often the last to know.”

The muqqadim agreed. “We can’t blame the family. They didn’t know. They never know. It’s very hard on them. There’s no reason to punish them.”

“Whose fault is it?” I asked. “How about Adelillah Fathallah?”

Fathallah was the imam of the al-Rohbane mosque. The mosque was affiliated with Dawa Tabligh, a generally nonviolent social movement that preaches and proselytizes in the name of Islam and the doing of good works—not a political movement. The mosque, under Fathallah’s sway and beginning with Kounjaa’, had become known in the neighborhood as the Afghan mosque. All five of the young when who went to Iraq to be martyrs regularly prayed there. Fathallah was arrested on December 26, 2006, after the last of the group had gone to Iraq and the first reports of their actions had come back. He was sentenced to six years.

“Did Fathallah’s preachings convince them to go?”

“No, he didn’t convince anyone to go to Iraq,” the muqqadim said with surprising certainty. “He helped those who already had made up their minds to go.”

At the soccer field in the local schoolyard, Ami (“Uncle”) Absalam, the volunteer coach of the Mezuak soccer league, said that now that there were regular soccer practices at the schoolyard, the kids were kept busy and away from bad influences.

He thought the most important link between the Madrid plotters and the young men bound for Iraq was through Kounjaa’, who was a regular guy from the neighborhood as well as a preacher of jihad who commanded respect, and who was crucially also related by marriage to one of the Iraq-bound friends.

“Hamza would play at Gharza [“the garden,” a makeshift soccer field] with Kounjaa’ and others,” Ami Absalam told me. “I would lend him the soccer balls to play there. Hamza admired Kounjaa’. But he would also play here with Bilal at the high school.”

Ami Absalam said he believed that soccer for young boys is the best antidote to violence, and so he devotes a good part of his life to helping to make soccer a passion for the boys. He receives no money for doing this day in and day out, year after year.

“I have three hundred kids here enrolled; they each pay two hundred dirham [twenty dollars] a year. If their families can’t pay, I try to find the money for them. They’re all basically good kids. And some of them are terrific. We have here many who could be with Real Madrid or Barça. We have lots of Zinedines.”

He’s a dynamo who spreads his high spirits to all those around, but suddenly his shoulders sagged. “But look at what we have to play with.” He hauled up a large net bag loaded with soccer balls: all torn and frayed, and nearly deflated. “How can you learn to become great with that?”

Then he rebounded: “Just give these boys shirts and shoes and soccer balls, and they’ll be all right. Some will become great players. And they won’t have to go get out their tensions in other ways.”

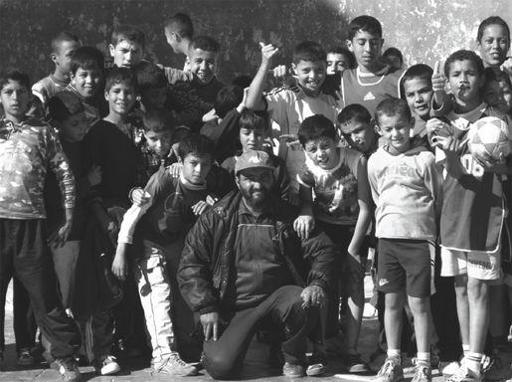

Ami Absalam (center) and his soccer boys.

GROUPTHINK

For Americans bred on a constant diet of individualism, the group is not where one generally looks for explanation. This, as I noted at the beginning of the book, was certainly true for me. But science tends to support the finding that groupthink often trumps individual volition and knowledge, whether in our society or any other. In 1955, social psychologist Solomon Asch wanted to investigate what human beings would do when confronted with a group that insists that wrong is right. In his experiment, he showed groups of seven college students the drawing of a line, and then asked each student to identify which of several other lines matched it in length. Only one student, however, was being tested. The others were in on it with Asch and were only acting. The actors all picked the same blatantly wrong answer. Seventy-five percent of the subjects then chose the wrong line, rather than the line their own observation indicated was the correct one.

My research colleague Greg Berns, a physician and psychologist, has done brain imaging studies with his associates at Emory University using the Asch experiment. He found that subjects appeared to reach conformity by recalibrating the figure in parts of the brain dedicated to visual processing (occipital-parietal network) rather than to executive reasoning and decision making (prefrontal cortex). This suggests that people might actually picture reality differently under peer pressure. The results also indicate that to stand alone and resist conforming may be emotionally costly (for example, in being associated with increased activity in the amygdala, a “primitive” brain structure the shape and size of an almond that has long been linked with a person’s emotional state).

1

Recently, psychologists at Temple University in Philadelphia found that adolescents and young adults between ages thirteen and twenty-three were more inclined than adults were to take risks under peer influence of three or more friends. One study, dubbed the Chicken Experiment, used a driving-simulation game to see which age groups take more risks in deciding whether to run a yellow light. Results showed that “although the sample as a whole took more risks and made more risky decisions in groups than when alone, this effect was more pronounced during middle and late adolescence than during adulthood.”

2

Indeed, most crimes by teens and young adults are perpetrated in packs. Sociologist Randall Collins finds that gangs and rioters (and police who try to control them) commit most of their violence when a cluster of four or more act in concert.

3

Part of the answer to what leads a normal person to become a terrorist may lie in philosopher Hannah Arendt’s notion of the “banality of evil,” a phrase she used to describe the fact that mostly ordinary Germans, not sadistic lunatics, were recruited to man Nazi extermination camps.

4

In the early 1960s, psychologist Stanley Milgram tested Arendt’s thesis.

5

For his experiments, Milgram recruited a number of college-educated adults, supposedly to help others learn better. When the “learner,” hidden by a screen, failed to memorize arbitrary word pairs fast enough, the “helper” was instructed to administer an electric shock and to increase the voltage with each erroneous answer. (In fact, the learners were actually actors who deliberately got the answers wrong, and unbeknownst to the helpers, no electrical shock was actually being applied.) Most helpers complied with instructions to give what would have been potentially lethal shocks (labeled as 450 volts) despite the learners’ screams and pleas.

Although this experiment specifically showed how situations can be staged to elicit blind obedience to authority, a more general lesson is that manipulation of context can trump individual personality and psychology to generate apparently extreme behaviors in ordinary people. In another classic experiment from more than thirty years ago, the Stanford Prison Experiment, normal college-age men were assigned to be guards or prisoners; the “guards” quickly became sadistic, engaging in what psychologist Philip Zimbardo called “pornographic and degrading abuse of the prisoners.”

6

It’s hard to think of a torturer as just your average Joe, but other studies indicate it’s true.

7

Most of the American soldiers who humiliated detainees in Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison were probably no different.

Other research on groupthink indicates that when people are given information about the specific ability-related or morality-related behaviors that others say they will perform, these people come to believe that they also will perform such behaviors.

8

If group cohesion is based on how much the members like the group and get along with its members, then the members are less likely to speak up against the group norms, and the group is more likely to make poor decisions. This is because like-minded individuals in a group are more concerned with their social relations than with their tasks; they are less prone to cause conflict within a group in order to maintain congeniality. When you couple this with the reality bias wherein group members believe others to be more extreme than themselves, then the whole group tends to shift to a more extreme position as people bend over backward to accommodate to what each believes is the others’ more radical position. Social psychologists refer to this particular group dynamic as “extremity shift” or “outbidding,” which is responsible for a “bandwagon effect,”

9

whether in the rush to support a patriotic war or the cause of martyrdom.

But there’s more to group dynamics than just the weight and mass of people, their behavior, and ideas. There are also the structural relationships between group members that make the group more than the sum of its individual members. It’s also the networking among members that distributes thoughts and tasks that no one part may completely control or even understand.

It’s not that hard to grasp how networks transcend individual limitations of physical and mental power to get things done. Anyone who has ever worked on a team or a production line knows that. But networks also have more far-reaching properties that enable them to transcend physical constraints of space and time in surprising ways that are only now beginning to be understood by science.

Take obesity. “What does obesity have to do with terrorism?” you may reasonably ask. Well, nothing … and everything. Consider:

A recent medical study shows that even body weight can be strongly influenced by social networks of friends.

10

Researchers examined a densely interconnected social network of over twelve thousand people from 1970 to 2003. A person’s chances of being obese increased by 57 percent if a friend became obese, 40 percent if a sibling became obese, and 37 percent if a spouse became obese. The study suggests that these trends cannot be attributed to the selective formation of social ties among people who might naturally incline to obesity. The biggest influence comes from close mutual friends, even if they live far away. The faraway friend has even more influence on your weight than do neighbors or even relatives who live with you. Although subsequent studies may show that there are other causal factors involved in these long-distance relationships, the results clearly have as much or more to do with social ties than with genes or physical proximity.

If even body weight can be significantly molded by social networks in fairly short order, and perhaps even across great distances of physical separation, think how much easier it is to motivate ideas, behaviors, and emotions among friends in neighborhoods or in chat rooms over the Internet. Indeed, studies now show that smoking, happiness, and even loneliness are also like viruses that spread best among friends. The key difference between terrorists and most other people in the world lies not in individual pathologies, personality, education, income, or in any other demographic factor, but in small-group dynamics where the relevant trait just happens to be jihad rather than, say, obesity.

11

This is what I mean by the ordinariness of terror.

It’s not likely that we will ever be able to prevent terrorist attacks by trying to profile terrorists; they’re not different enough from everyone else in the population to make them remarkable. Insights into homegrown jihadi attacks will come from understanding group dynamics even more than individual psychology. Small-group dynamics can trump individual personality to produce horrific behavior in ordinary people, not only in terrorists but in those who fight them. Although we can’t do much about personality traits, whether biologically influenced or not, we may be able to think of ways to make terrorist groups less attractive and undermine the spell they cast for young people. Can we help to offer other prospects for normalcy and a better choice than just Marc’s question: “Ronaldinho or Osama?” That’s a likely key to moving the young away from the enveloping ordinariness of terror and collective violence.

Take up the white Man’s burden—Send forth the best ye breed—

go, bind your sons to exile

Other books

Hold On (Delos Series Book 5) by Lindsay McKenna

Shady: MC Romance by Harley McRide

Bombshell by Mia Bloom

Flesh: Part Eleven (The Flesh Series Book 11) by Corgan, Sky

Epiphany Jones by Michael Grothaus

El Cadáver Alegre by Laurell K. Hamilton

The Unlikely Time Traveller by Janis Mackay

Don't Lose Her by Jonathon King

Sneak Attack by Cari Quinn

The Haunted Carousel by Carolyn Keene